By Bernard E. Harcourt

On Saturday, January 12, 2019, yellow vest protesters demonstrated in cities across France—from Paris to Bourges, Bordeaux, and Toulouse—in what they called “Act IX” of the yellow vest movement. According to the official count by the ministry of the interior of the French government—an interested party, since the French State is the very target of the protests—there were 84,000 protesters across the country, and they faced an equal number of law enforcement officers from the national police, CRS, and gendarmerie. 80,000 policemen and women were mobilized and deployed around the country to manage any possible unrest—along with military-grade armored vehicles, flashballs, water cannons, etc.—resulting in an astounding one-to-one ratio: one police for every yellow vest.

The number of yellow vests at Act IX was up slightly from the week before, and seemed to signal that the yellow vest movement, which began on November 17, 2018, is not dissipating. The conjuncture on January 12 was especially important: President Emmanuel Macron was slated to deliver his “Lettre aux français” the next day, and the great “national debate” over the political questions raised by the movement was scheduled to begin in three days.

I’d read extensively about the movement and spent Saturday afternoon, January 12, 2019, informally observing the protest at the Étoile and along the Champs-Élysées. Compared to other Saturdays, Act IX was relatively peaceful, with the weight of power on the side of the overwhelming police force. There were, to be sure, teargas canisters fired and the police used water cannons; but compared to other previous protests—and to ordinary protests in Paris, especially at the “tête de cortège”—the space of protest was relatively subdued.

Along the Champs-Élysées, steps from the CRS, police, and gendarmes, yellow vest protesters tagged the fortified and boarded-up banks and stores, while a few other Parisians and tourists nearby continued to shop in the luxury boutiques.

The yellow vest movement has been aptly described, by Étienne Balibar and Toni Negri, as a “contre-pouvoir,” a counter-power, perhaps one of the only counter-powers to President Macron now in place. Truth is, all of the potential institutions that could serve as a check to executive power are essentially missing-in-action. The Assembly was filled with Macron’s hastily assembled delegates. The Sénat is hardly to be heard. The judiciary does not play that function in France. The major oppositional parties—the Socialist Party on the left and the Republicans on the right—imploded and have disappeared. The paper press is pretty docile (predominantly opposed to the yellow vest movement). The few voices that can be dimly heard are Jean-Luc Mélanchon’s insoumis on the farther left and the new Rassemblement national of the far-right (formerly the Front national). As a result, the yellow vests really do stand as the counter-power to Macron. Apparently they have the support of a majority of the French. 72% of the French supported the movement as of December 1, 2018; it is widely believed that a majority of the French still support them now, even after a series of unfavorable videotaped incidents that went viral.

In an early essay published December 8, 2018, Étienne Balibar presents a nuanced diagnosis of the movement, locating it within the present crisis of neoliberalism and drawing its Gramscian element as a potential “reversal of hegemony.” Ludivine Bantigny, in a forthcoming essay, situates the uprising in the context of unprecedented inequality and calls it “un événement.” Toni Negri, in a series of essays, sees the multitude in the yellow vests, but warns of what he imagines may come: “a long period of repression.” Balibar ends by offering guidance as to how the movement could gain momentum, specifying:

I therefore suggest that all this could be given concrete form, opening up a dialectic of self-representation and governmentality, if municipalities (starting with some of them that set an example: those most sensitive to the urgency of the situation or most open to democratic invention) now decided to open their doors to the local organization of the movement, and declared themselves ready to pass on its demands or proposals to the government.

I would take a different angle. I have no standing, nor any interest in assuming the position of what one might call “the counselor to uprisings.”[i] Nor do I subscribe to the various roles that intellectuals have assigned to themselves or to others in the late twentieth century—whether it is the “intellectuel universel” supposedly modeled on Jean-Paul Sartre, the “intellectuel specific” that Michel Foucault embraced, or even the middle-ground “intellectuel singulier” that Balibar uncovers in his most recent book, Libre parole: “Un intellectuel qui essaie de dire ce qu’il en est du present, de ses droits et obligations, de l’intolérable et du possible qu’il recèle.”[ii] No, I do not consider myself—nor would want to present myself—as an intellectual, but instead, simply, as someone who acts, who implicates himself, who rises up at times, breaks silence at others, litigates most often. I cannot counsel or critique other people’s struggles. I can only critique my own political engagements. In my seminar, Praxis 13/13, I’ve been working through the relation between theory and practice, and at least tentatively, for the moment, have realized that I cannot do critical philosophical work on other people’s political engagements, but only on my own. This imposes on me, I believe, a duty to act—to engage politically, to perform praxis, as the very precondition to critique, but critique and praxis of my own actions.

And so the question I would want to raise is different, but pointed, and pointed at myself: On Saturday, at the Étoile, why did I not sport a yellow vest? Why do I not consider myself part of the yellow vest movement? Why did I remain an observer?

After all, it is a political movement that challenges, at its heart, many of the contemporary political formations that I target in my own political writings and interventions. First, it is aimed, in large part, at neoliberalism and the start-up uberized culture that does not provide for the welfare of people. As Toni Negri suggests, the movement represents the “expression of a rejection of the logics of neoliberalism—a rejection probably brought against those logics in a moment of acute crisis.” There is substantial overlap here with my views on neoliberalism. Second, the movement targets police excess and the police state. I’ve been challenging that in the United States for decades. If you listen closely, for a moment, to the grievances of the yellow vests, you hear clearly those of the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Take for instance, the spoken words of Christophe Dettinger, a retired boxer (French light-heavyweight champion in 2007 and 2008) and self-identified yellow vest. There was a lot of controversy surrounding Dettinger because he physically assaulted a policeman at the protests in Paris on January 5, 2019. The video went viral, as did his apology—both of which you can see here at the Guardian. Supporters of his quickly raised over 110,000 euros on a crowd-funding site, Leetchi, which was shut down by political opposition, in outrage. He then posted this apologia, qua-political manifesto, which he recorded on YouTube to explain himself to his fellow yellow vests:

Chers amis gilets jaunes,

Voilà, je me présente. Je m’appelle Christophe. […] Je voulais vous présenter les choses comme je le sens.

J’ai participé aux huit actes. […] J’ai fait tous les manifestations du samedi sur Paris.

J’ai vu la répression. J’ai vu la police nous gazer. J’ai vu la police faire mal a des gens avec des flashballs. J’ai vu des gens blessés. J’ai vu des retraités se faire gazer.

Moi, je suis un citoyen normal. Je travaille. J’arrive à finir mes fins de mois, mais c’est compliqué.

Mais je manifeste pour les retraités, le future de mes enfants, les femmes célibataires…

Je suis un gilet jaune. J’ai la colère du people qui est en moi.

Je vois tous ces présidents, je vois tous ces ministres, je vois tout l’État se gaver, se pomper. Ils ne sont même pas capables de montrer l’exemple. Ils ne montrent pas l’exemple. Ils se gavent sur notre dos. C’est toujours nous les petits qui payons.

Je me sens concerné parce que je suis français. Je suis fier d’être français. Je ne suis pas d’extrême gauche, je ne suis pas d’extrême droite. Je suis un citoyen lambda. Je suis un français. J’aime mon pays. J’aime ma patrie. J’aime tout.

“C’est toujours nous les petits qui payons”: notice that this is not so much Marxist class struggle as French revolutionary talk. The enemy is not the bourgeoisie or the managing class, but the State—the presidents and their ministers. It is pitched in a decidedly ancien régime register. His discourse is tinged with citizenship and patriotism. He emphasizes repeatedly that he is a citizen, that he loves his country and his homeland. I would hesitate to jump to the conclusion that he is xenophobic or anti-immigrant position; he may, possibly, simply be trying to emphasize that he’s not a habitual protester and bears no animus to France. (I’ll come back to this). His claim that he is neither an extreme leftist or rightist is important. He’s trying to deny ideology. ‘This is not about political ideology,’ he is essentially saying, ‘it is not about party politics either.’ All presidents and ministers, regardless of their party, are corrupt and exploit the little man.

Much of this discourse resonates with leftist ideals of equality and anti-neoliberalism. Many of the positions of the yellow vest movement strike me as important, strategically astute, and sympathetic. So why did I not don a yellow vest?

Here are a few reasons why I hesitated. First, out of concern that there is a latent identitarian dimension to the protest that does not equally valorize the suffering of persons of color or of others who are marginalized in the banlieu or have been struggling to decolonize France for decades along dimensions of race, post-colonialism, ethnicity, gender and sexual difference, to name a few. Second, out of concern about the patriotic, nationalistic language and symbols. I’ve argued elsewhere that we have not paid sufficient attention to the words Donald Trump has used and, as a result, have not recognized the neo-fascist, white supremacist, ultranationalist turn in the US. I need to assure myself, and investigate further, that the yellow vest appeals to citizenship, nationality, and patrie in their declarations and manifestos are not in fact New Right.

So for now, rather than put on the yellow vest, I would take on the mantle of “companion de route” – fellow traveler, like those who, famously, in the twentieth century, did not join the Communist Party, but sympathized with the aims and goals of Communists and were willing to work with the movement. The role of fellow traveler is perfectly suited to my current position vis-à-vis the yellow vests because it allows me to highlight the degrees of separation. It allows me to spell out, clearly, the lines that I would draw:

- I reject any affirmative or prescriptive nationalism: it may be okay to be proud to be French (or Algerian, or Haitian, or American for that matter) in a cultural sense (even if there are so many dark sides to all these histories, from collaboration with the Nazis, to Papa Doc, to slavery); but it is never okay to denigrate others for having a different identity. National pride in itself is not necessarily out of bounds; but there is no room for discrimination on the basis of national origin and no place for patriotism as a normative grounding of the movement. Citizenship cannot serve as a source of distinction

- I reject any xenophobic, racist, ethnic, sexist, or sexual phobias: here too, there is absolutely no place in a popular movement like this for discrimination against those who are, perhaps, even more marginalized than the working class.

- I reject the call to a “people” defined in ethnocentric ways: insofar as there is reference to a “people,” and therefore a “populist” dimension to the movement, it has to have a porous boundary that does not serve to exclude or police identity. The term “the people” has to be understood merely as the “collective assembled,” not the Volk.

Those are lines that I will not cross, in my own praxis, and for the moment they push me to guard against wearing the yellow jacket, while standing beside the protesters and being a fellow traveler. The term “compagnon de route” seems more appropriate than ever—with the movement taking over the “rond points” on the roads and highways across France, the symbolism of the road safety vest, and Macron being “en marche!”

***

Being a “compagnon de route” allows me to express some areas of doubt, other areas of admiration, and some of simple astonishment.

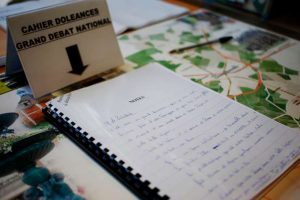

First, though, admiration. It is remarkable that the yellow vest movement has raised such critical issues of inequality and social injustice so quickly in, apparently, such a spontaneous and autonomous way—in the sense that it is not the product of an established political party calling its constituents to action, nor of a clear political ideology. It is stunning that, in such a short span of time, it has mobilized a counter-power in France made up of what might be called, by analogy, the 99%. The fact, for instance, that the country, only two months later, is going through a process of people hand-writing their grievances in “cahiers de doléances” in mairies (city halls) around France is simply amazing and historically haunting.

Negri writes that “There is undoubtedly in France a multitude that is rising up with violence against the new misery wrought by neoliberal reforms.” It may be great in number, but it does not feel to me like a collective or a multitude. I am struck by the individualized nature of the uprising seeking community: it has the appearance of individual actors, or small family units, rising up as single individuals, just themselves, as “person lambda,” and finding others who are also exasperated, rather than a community or multitudinal uprising. It feels as if these particular individuals want to make themselves heard.

From what I could tell from my own observations on Saturday, January 12, 2019, but also from what I have read, many of the yellow vests in Paris had come with their spouses or partners and a few friends—women and men, some partnered, accompanied by friends. They were wandering around, somewhat unsure of the process, unsure of the rules of protest, trying to stick together. I heard many of them looking out for each other—asking each other where their friend who came with them was, for instance.

The leaderless aspect of the movement is brilliant, strategically—and picks up perfectly on notions of political disobedience from the Occupy Wall Street movement. It protects the movement from appropriation, as well as from being sullied by any one individual. It reflects the idea that the individual protesters do not want to be represented, or spoken for, but want to present themselves. They want to engage the political field in their own terms and in their own words. One older protester was sitting on a bench on the Champs-Élysées, with a megaphone, orating. A woman sat next to him, approvingly, perhaps his wife. Other protesters would walk by, listen, engage, chat, clap at times, and then move on. But he was really just expressing himself—and his indignation.

If there is one unifying theme, it is the one constant refrain: “Macron, demission !” [“Macron, resign!”]. I even heard a few times, “Macron, en prison !”—which oddly reminded me of the MAGA call to “Lock her up.” But, yes, the one theme that seems to unite most of the protesters is a certain hatred, a visceral hatred, of Macron Rex. His personality, his discourse, his attitude drives the yellow vests over the edge. Not that surprising when he openly declares that too many French people (especially the young) don’t make an effort or when he starts his mandate by lifting the tax on fortunes and then proceeds to knickle-and-dime the pensioners and poor. In any event, the feeling is palpable. In effect, what is rallying these protesters is their collective hatred for what they perceive as a monarchical or Napoleonic figure. I had seen this and experienced it during the last protest I attended in Paris on May 26, 2018, with my friend and colleague at Columbia, Thomas Dodman. In fact, we had captured it in an image of Thomas in front of the typical poster at the Place de la République:

The sentiment has, if anything, intensified. It is now omnipresent. It practically defines the movement. And this, of course, complicates things for many on the Left, because the protest is then perceived as a referendum on Macron’s policies, including his support of Europe, of climate reform, etc. It is precisely because of this that many on the Left oppose the yellow vest movement, as a threat to the Europe Union or more cosmopolitan politics. (During the election, naturally, many on the Left opposed Macron and would have preferred another candidate, but now that he is president, many prefer to work within the political system than try to expulse him from the Élysée and deal with the unknown, especially the possibility of an extreme right replacement.)

It was also admirable and politically meaningful to be on the Champs-Élysées for a mass demonstration. They usually are in the less wealthy neighborhoods in Paris, mostly around the Bastille and the Place de la République. This is another striking feature of the yellow vest movement: they are directly confronting the extreme wealth inequalities and excess consumption in the space of excess luxury. The battle cry for this past Saturday’s protest, somewhat amusingly, was “On va faire les soldes à Paris!” (Libération), and the intention was to march on the Grands Boulevards, precisely where all the large department stores are located. Of course, the cortège went through the Place de la Bastille, since it began further east at Bercy, where the ministry of finance is located; but the rallying point was, and has always been, the Étoile. The fact that the protests are taking place at the “chicest” neighborhood of Paris is telling. It’s a protest aimed at wealth inequality and the excesses of the elite.

Most banks are boarded up, even outside the path of the Saturday marches. So, for instance, even in the Latin Quarter, on the Left Bank, far from any of the marches, the BNP and Société Générale branches are now permanently boarded up—not just on Saturdays or weekend, but permanently. Banks in Paris have become symbol and now incarnation of fortress capitalism.

Equally surprising, the boarded-up and secured luxury stores near the Champs-Élysées remain open, and a few wealthy-looking customers are still shopping, only meters away from the protest. I was amazed to see luxury stores like Fendi, Gucci, and others, guarded by private security, boarded up, gated (in the sense that the doors and any windows have iron gating on them), but nevertheless open to a handful of swanky buyers. It felt surreal. In the background, you could hear flashballs.

Second, then, outrage. At the Étoile, it felt that there were more police officers than protesters. Le Monde reports that there were 80,000 police officers deployed around the country, which is about as many as the official count of protesters: a one-to-one ration. (If only education were like that! Could you imagine one teacher for each student? What a beautiful world that would be!)

On the West side of the Étoile, I heard a gendarme order protesters within the perimeter to take off their yellow vests if they wanted to go outside the perimeter. The protesters were blocked in by a row of shielded police officers, and he told the protesters, loudly, “If you want to leave, you first need to take off your yellow vest, line up, and then go through there,” pointing. Not sure if he said something about being checked, or searched. (The police were searching bags for sure of anyone crossing the lines.) It felt odd to hear the officer order people to take off their yellow vests as a condition of exiting the protest. It almost reflected the State’s tangible fear.

The hardware was impressive. The tanks, the armed trucks with shovels and water cannons. The massive number of paramilitary officers. I understand, of course, that there is vandalism and broken windows, also that there have been injuries. But still, the amount of police was overwhelming. It is so plain, today, that liberal democratic regimes rest on the police state.

Third, other doubts. The act of putting on the vest, of wearing it, is the only thing that identifies anyone as a member of the protest group. It’s a small act. Now, you definitely have to be committed to enter the perimeter of the protest wearing a yellow vest, because it is heavily policed by armed paramilitary officers. Not everyone is willing to walk up to a CRS in full gear and ask them to go through the perimeter into the fray. But most who are used to protesting will, and will easily don the vest.

It is worth spending some time thinking about this aspect: you become a protester by physically putting on the jacket. It slips over any clothes, easily. You can put it on and take it off easily. It’s a bit like the pink hats from the Women’s March against Trump. The only real cost is the fear of being accosted or confronted by someone else or by the police. This, of course, means that it may be at times difficult to differentiate protesters from those who are there to rumble with the police, entertain themselves, or simply there out of curiosity. But then again, the “official” count on Saturday, January 12, 2019, was 84,000 people across France (and official counts tend to underestimate.) That is a large number. It is hard to imagine that the question of authenticity would involve anything more than a fraction of those present.

Perhaps the very question of authenticity is inappropriate with a popular, grass-roots movement like this; but the fact is, there is no party to belong to, nor any ideology to subscribe to. There is just, it seems, a rageful sense of indignation shared by these women and men that seems to compel them to don the yellow vest and demonstrate their political anger. A “casseur” (defined as someone who joins the protest and breaks windows, loots, or vandalizes) may also be full of anger and indignation at their political and economic condition, so they may well be the perfect illustration of a yellow vest protester. After all, crime is political. Penal law is political practice as Foucault so brilliantly demonstrated in Penal Theories and Institutions in 1972. Rioting is an uprising. It’s not clear, in the end, whether we should engage in an exercise of policing the margins of the protest movement–though it continues to trouble me. Toni Negri discusses this as well in his essay here.

Finally, surprise. Honestly, I am somewhat surprised at the discourse surrounding the vandalism and acts of violence. Many of my leftist colleagues complain that these yellow vests are “des voyous” (thugs, hoodlums). And there is no doubt there have been incidents of violence. But it is hard to characterize a predominantly peaceful day of protest in this way. Returning to the retired boxer, Christophe Dettinger, for a minute: Many people, including people on the Left, appropriately decried the assault—it made the cover image and headline of a major weekly. And many point to him as evidence of the hooliganism of the yellow vests. But I have to say, I find it hard to impugn a movement of 84,000+ protesters on the basis of one or a few of them who turn violent. To dismiss the movement as “une bande de voyous” because a minute fraction of them turn to violence—in a massive movement built on anger—seems irresponsible to me.

In the end, then, these admirations and doubts, and questions, leave me at least for the moment, tentatively, a “compagnon de route” to the yellow vest protest. In this way I hope, at least, to emphasize the places where I would not skid off the road—under any circumstance.

Notes

[i] Etienne Balibar, Libre parole (Paris: Galilée, 2018), p. 111.

I mentioned your blog post to a young Parisian and indicated that you specifically asked why you had chosen not to wear the “gilet jaune”. He guessed — wrongly, although it’s the explanation I would have given — that it was because you didn’t want to participate under false pretenses, that your doléances are not the ones that motivated the movement in the first place. University professors have plenty of reasons to complain (and have complained) about Macron’s policies, and if my colleagues decided to join the protest one Saturday, as professors, but wearing their gilets jaunes, it would be seen as perfectly natural.

The more pressing question: have gilets jaunes been invited to tomorrow’s seminar? Can you imagine circumstances in which it would be inappropriate not to invite them?