By Brandon Vines

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights; that among them is life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” [1]

The language of the Declaration, according to Chief Justice Taney, “would seem to embrace the whole human family.”[2] However, “it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included.”[3] At the core of Taney’s reasoning in Dred Scott was a simple continuity—Black Americans were never intended to be part of the we the people.

Abolition 4/13 addressed how the continuity of civil exclusion was not just from the Founding to Dred Scott, but from the Founding to the present. An honest we the people has yet to exist. In envisioning an abolitionist future, the connective tissue between the present and the past must be accounted for. “In using the words ‘prison abolition,’ many activists, former prisoners are not speaking metaphorically,” Professor Childs explained, “it’s a non-metaphoric recognition of the connections between prison slavery and chattel slavery.”[4] In a small practice of abolition democracy, this essay takes an approach of arguing for the abolition of one idea and works to build another in the former’s stead. First, I outline the ideas raised by the panelists regarding the “non-metaphorical” continuity between slavery and modern institutions. Second, I begin to fill-in some of the historical narratives introduced by the panelists. In both parts, I focus particularly on the continuity between slavery and the prison system.

Continuity not Metaphor

This section pulls from the Abolition 4/13 discussion, readings, and contemporary events to sketch out what Childs meant by abolition not being a metaphor. Since the focus in this section is to both recap and synthesize the ideas raised earlier, it will heavily focus on quotations from the panelists and sources. Each panelist will be discussed in turn.

Professor Jones-Rogers explained that “slavery wasn’t really abolished, but merely refashioned and renamed. Black people understood this and they continued to recognize how the vestiges of the institution continued to constrain and stifle black liberation.”[5] As Jones-Rogers notes, this idea has deep roots. In her pre-seminar article, Jones-Rogers said: “No matter how [formerly enslaved people] initially responded to the news, they came to understand that the abolition which their oppressors envisioned was empty, that their oppressors’ ‘freedom’ came with nothing.” Du Bois saw this too; thirty years before he exhaustively explained the continuity of slavery in Black Reconstruction (1935), the same idea was at play in his The Souls of Black Folk (1903):

“There can be no doubt that crime among Negroes has sensibly increased in the last thirty years, and that there has appeared in the slums of great cities a distinct criminal class among the blacks. In explaining this unfortunate development, we must note two things: (1) that the inevitable result of Emancipation was to increase crime and criminals, and (2) that the police system of the South was primarily designed to control slaves.”[6]

Written only twenty-five years after Reconstruction ended, Du Bois’ words are a powerful indictment of Emancipation’s functional hollowness.

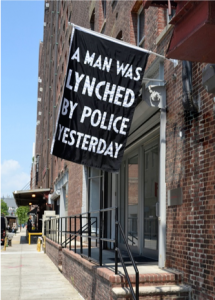

Left: The original “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” flag outside the NAACP building in 1936 (source). Right: Artist Dread Scott’s 2015 reimagination of the NAACP’s flag (source).

The two images above foreground how the form of oppression may change with time, but the substance remains intact. In explaining why he created the modern NAACP flag, artist Dread Scott said, “the past sets the state for the present but also exists in the present in a new form.”[7] In another interview Dread Scott elaborated: “I think that saying a man was lynched by police actually brings up an important history in this country in a way that I think people get[, b]ut that’s not spontaneously how they view it.”[8] For many, particularly those most directly affected by slavery’s afterlives, the connection is intuitive. Dread Scott quoted a participant in his Slave Revolt reenactment who said “Look, I used to be in prison and now I am embodying somebody who is free.”[9]

Professor Childs’ intervention gives this essay it’s title, when he tells us “abolition is not a metaphor.”[10] Childs points to several first-hand accounts, each explaining their own experience. In one, he explains how for some, the “experience of solitary confinement enact[s] a kind of bending of time…where the liberal white supremacist notion of a kind of neat, progressive passage from the back-then of slavery to the now of freedom, is shown to be completely obliterated for the black captive.”[11] For Childs, the experience and work of imprisoned intellectuals is the wellspring of prison abolition. Child brings a second key idea to the discussion. “To treat of slavery and the prison. . .as two parts of a kind of continual repression of black people [is] considered an anathema.”[12] The panic around the New York Times’ 1619 Project or the modern investment in denying the existence slavery’s modern impact evidences what is at stake.

The populist resistance against acknowledging the enormity of the continuity between slavery and its modern-day afterlives is evident in political rhetoric. In proposing his own “1776 commission” in reaction to the NYT’s 1619 Project, Donald Trump said:

“[T]he left-wing rioting and mayhem are the direct result of decades of left-wing indoctrination in our schools. . . .Our children are instructed from propaganda tracts. . .that try to make students ashamed of their own history. The left has warped, distorted, and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies. There is no better example than the New York Times’ totally discredited 1619 Project. This project rewrites American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom. Nothing could be further from the truth. America’s founding set in motion the unstoppable chain of events that abolished slavery, secured civil rights, defeated communism and fascism, and built the most fair, equal, and prosperous nation in human history.”[13]

Trump went on to similarly denounce Critical Race Theory. His speech is indicative of the reaction Childs denoted. Trump simply asserts as a priori truth the narrative he and many Americans find more comfortable. The facts behind the 1619 project are never mentioned nor countered.

Professor Glass explained how honest narratives of abolition were papered-over by “a history that focused on the deeds and limitations of white abolitionists who were unwilling or unable to challenge the status quo upon which they benefited.”[14] De Bois described the same historical slight-of-hand in Black Reconstruction, where historians at Columbia and John Hopkins, with “endless sympathy with the white south…and silence for the Negro,” redefined the history of abolition.[15] In the end, Du Bois explains, “the whole criminal system came to be used a method of keeping Negroes at work and intimidating them.”[16]

However, Glass offers a rallying cry. The reclamation of an honest history “giv[es] rise to a new set of questions for lawyers and activists, as to what that history that’s been illuminated once again . . .can teach us about the past. And what’s at stake in even asking the question about finding a usable past.”[17] Professor Harcourt, pulled these threads together, explaining:

“This is not a metaphor. In fact, the whole intervention is non-metaphorical in the sense of trying to find the exact connections and actually doing that work. Part of it is the historical work, part of it is just returning to the texts. But doing that work to show that the transformation from the de jure enslavement. . .to a system of de facto racial hierarchy and a caste system is not metaphorical and we see it precisely by the use of the criminal law following emancipation.”[18]

These aren’t metaphors. “Prisons have thrived over the last century,” according to Angela Davis, “precisely because of the absence of [post-Emancipation social institutions] and the persistence of some of the deep structures of slavery.”[19] The shortcomings of the abolition of slavery continue to be felt today because slavery’s successors remain alive. The abolition movement today is not a metaphorical harkening back to Emancipation, but, rather, an increasing desire to finish the work left undone by the abolition of slavery.

Unburying History

The remainder of this article will try to isolate one of the sinews connecting slavery to the modern day. Although emancipation ended de jure slavery, a relentless campaign of semi-official killings was an essential tool in establishing a de facto reinstatement of slave system. This section argues that the modern death penalty has its roots as a formalization of the racialized terror of Reconstruction, which, in turn, was an attempt to maintain white domination following Emancipation.

Though necessarily incomplete, Freedmen’s Bureau records offer some insight into the unchecked violence of Reconstruction. The records from Georgia the most complete and are illustrative. In 1867 and 1868, several black people were legally hanged in Georgia; many more were simply lynched or murdered with impunity. Mary Wright, accused of killing a mule, was dragged out of the jail and hanged. William Hardaway, a black man, was shot dead by his white employer because Hardaway had objected to his son being taken into town by the employer. The employer was not arrested. During this period, the most severe punishment given by Georgia courts to a white offender with black victims was 20 days imprisonment. In most cases, white offenders escaped with no punishment.[20]

The record from this period also demonstrates a tyranny of assaults. In Thomasville, a black child was severely whipped by a white man. The child’s parent had informed the white man’s spouse that the man had visited the saloon. The courts did nothing. Andrew Price, a black man, was stabbed by a white student in Athens. Price had failed to bring the student a coffee swiftly enough. The student was fined $50, one of the steepest penalties meted out.[21]

Death as a weapon of racial terror was not limited to individual targets. White anxieties, particularly around elections, could be whipped into a state of hysteria and dozens of pogrom-like attacks are recorded, with the 1866 Memphis Riots being among the most well-known. Typical, though, are the events in Eutaw, Alabama during the 1870 election. Approximately 80 percent of Greene County residents were black. With the vital support of black voters, Republicans had carried the county with 2,000 votes for Ulysses S. Grant in 1868. The Ku Klux Klan unleashed a campaign of brutal terror to wrest control of Greene County from “Negro Rule.” In May, 30 horsemen in black robes calmly entered downtown Eutaw. They entered a hotel and shot a Republican politician through the head. Nobody was prosecuted. In October, Klansmen descended on the Eutaw courthouse. There, 2,000 black and white Republicans were holding a political rally. The Klansmen opened fire, resulting in more than 50 wounded. The Democrat candidate for governor won Greene County by 43 votes. State officials did nothing.[22]

Mass and individual violence was defined by both impunity and routine occurrence. “[T]he ‘redemption’ of the South was in essence a terrorist campaign without parallel in American history. No reliable figures exist on the number of people who perished in the violent cataclysms of the Reconstruction years[; however,] between 1868 and 1871 alone the Klan may have killed as many as twenty thousand freed people.”[23]

These lynch mobs played an officially sanctioned role in maintaining the postbellum system. Lynchings were typically highly public and involved community participation. “Mock trials and confessions, even if obtained under torture, were essential to underscore the legitimacy of the punishment and to create the impression that the lynching was tantamount to a legal execution.” Indeed, in a very small number of cases the mock trial even led to acquittals. The presence of the “best citizens” of a community was used in the Southern press to justify lynchings.[24] Elected officials further legitimized lynchings. Many Southern politicians openly endorsed lynchings.[25] Public officials – including politicians and police – openly participated in lynchings.[26]

The most significant stamp of official sanctioning of lynching was the deafening silence of the legislatures, police, and courts. There was no want of evidence. Group photographs before lynched corpses were common practice and exchanged as postcards. Grisly mementoes were often claimed, traded, and kept. Spectacle lynchings were highly public affairs. Special excursion trains were scheduled to take onlookers from Atlanta to witness at least one lynching. [27] “Nobody was ashamed or tried to hide their identity. There was no reason to.”[28]

However, as the twentieth century progressed, social pressures increasingly pushed southern society from lynching and toward the death penalty. Lynchings, particularly highly public ones, peaked in the 1890s, with an average of 104 black people killed annually.[29] Over the coming decades, the south would slowly change. The viability of the sharecropping and plantation system collapsed and urbanization replaced it. As the “triumphal march of the automobile and radio put an end to the isolation of the South,” the publicity of lynching became an increasing source of anxiety to the white middle class. . . .Embarrassed by the increasing spotlight African American activists and a nationalizing culture shone upon lynching and fearing the loss of investment that might promote economic growth and prosperity in the region, middle class white southerners in the early twentieth century pressed instead for ‘legal lynchings,’ expedited trials and executions that merged legal forms with the popular clamor for rough justice.” The number of lynchings declined. Between 1901 and 1910, 75 black Americans were lynched annually. By the 1920s, the average was 55 black people murdered a year—almost half of the average in the 1890s.[30]

Lynching was not rejected by southern society, just the social consequences of overt racial terror were. Of all the lynchings committed after 1900, only one percent resulted in any lyncher being convicted of any criminal offense. Even then punishment was typically limited to fines or suspended sentences for offenses such as rioting or disorderly conduct.[31] The goal of white social control over blacks was not abandoned, merely the “extreme and increasingly embarrassingly public tool of lynching.”[32] The death penalty was the primary replacement. Southern leaders through editorials and speeches urged that capital punishment would ensure nearly the same degree of social control as lynching.[33] The transition was gradual but clear. The ratio of lynchings to state executions was 2.1 in the 1890s, the ratio flipped in 1915, and by the 1920s the ratio was 0.4 lynchings to every execution. While the death penalty eventually supplanted lynching, together they took a heavy toll of black lives in the intervening decades.[34]

Black lives continue to be devalued by capital tribunals. Today, significantly more innocent black people than sent to death row than any other group; this can be most readily seen in that while black people are roughly a quarter of the national population, more than a half of death row exonerees are black.[35] Innocent black people nationally are seven times more likely to be convicted of murder than innocent white people.[36] Counties with large black populations experience higher rates of death sentencing.[37] This is not a retrospective, because that implies distance. Rather, this section is an acknowledgment that the stream carrying us along has its ignoble headwaters in slavery. The abolition of the death penalty would not be a metaphorical sibling of the abolition of slavery, it would be a literal continuation of Emancipation.

Conclusion

In wrapping-up her remarks, Professor Jones-Rogers explained “since its founding American Democracy was premised on the full or partial exclusion of black people, even if it never stated this explicitly. . . .Perhaps, then, contemporary calls for abolition are on to something.”[38] I fully agree. Acknowledging that the struggle to abolish slavery is still being carried on today is a vital precept for our continuing discussions of modern abolition. Abolition is not a metaphor.

While we opened with the dehumanizing words of Taney, I would like to end with the far more meaningful words of Letetra Wideman, Jacob Blake’s sister:

“When you say the name Jacob Blake, make sure you say father; make sure you say cousin; make sure you say son; make sure you say uncle; but most importantly make sure you say human. Human life—let it marinate in your mind—a human life and his life matters. . . .this has been happening to my family for a long time. It happened to Emmett Till. Emmett Till is my family. Philando [Castile]. Mike Brown. Sandra [Bland]. This has been happening to my family.”[39]

Notes

[1] The Declaration of Independence para. 2 (U.S. 1776).

[2] Dred Scott v. Stanford, 60 U.S. 393, 410 (1856) (Taney, C.J., writing for the majority). A public version is available at www.supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/60/393.

[3] Dred Scott v. Stanford, 60 U.S. 393, 410 (1856) (Taney, C.J., writing for the majority).

[4] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:05:36, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=3936.

[5] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 59:37, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=3577.

[6] W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk 129 (1st Library of Am. ed. 2009). A public edition is available at www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm.

[7] Dread Scott, A Man was Lynched by Police Yesterday (2015), www.dreadscott.net/portfolio_page/a-man-was-lynched-by-police-yesterday.

[8] Angelic Rogers, Does This Flag Make You Flinch?, N.Y. Times (July 14, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/15/us/artist-flag-protests-lynching-by-police.html.

[9] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 31:57, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=1917.

[10] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:07:07, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=4027.

[11] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:09:41, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=4182.

[12] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:11:40, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=4301.

[13] Remarks by President Trump at the White House Conference on American History, The White House (Sep. 17, 2020), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-white-house-conference-american-history/.

[14] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 32:51, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=2571.

[15] W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction 718–19 (Free Press ed., 1998).

[16] W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction 506 (Free Press ed., 1998).

[17] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 43:17, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020) (emphasis added), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=2597.

[18] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:15:45, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=4545.

[19] Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy 92 (Seven Stories Press, 2005).

[20] Freedman’s Bureau, Report of Outrages and Murders 1866-68 Georgia, www.freedmensbureau.com/outrages.htm.

[21] Freedman’s Bureau, Report of Outrages and Murders 1866-68 Georgia, www.freedmensbureau.com/outrages.htm.

[22] Herbert Shapiro, White Violence And Black Response 12 (1988); William Rogers, The Boyd Incident, 21 Civil War Hist. 309 (1975); Manfred Berg, Das Ende der Lynchjustiz im Amerikanischen Süden, 283 Historische Zeitschrift [Hist. Z.] 583, 587 (2006) (Ger.).

[23] Manfred Berg, Popular Justice: A History Of Lynching In America (2011).

[24] Manfred Berg, Popular Justice: A History Of Lynching In America (2011); Margaret Vandiver, Lethal Punishment 177 (Rutgers Univ. 2005).

[25] See, e.g., Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Tom Watson Revisited, 68 J.S. Hist. 3, 16 (2002) (“With…a defense of lynching, [Senator Thomas] Watson’s Jeffersonian Magazine exercised considerable influence in Georgia politics.); Bryant Simon, The Appeal of Cole Blease of South Carolina: Race, Class, and Sex in the New South, 62 J.S. Hist. 57, 83 (1996) (describing Governor Coleman Blease’s vocal support of lynching, including his infamous, public “death dances,” which grotesquely reenacted lynchings).

[26] See, e.g., Anna Brutzman, 100 Years Later, Notorious Honea Path Lynching Remembered, Indep. Mail, Oct. 9, 2011 (detailing long-time state legislator Joshua Ashley leading a lynch mob with impunity).

[27] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching In America: Confronting The Legacy Of Racialized Terror, 3d ED. 28, 33, 34 (2017); Manfred Berg, Das Ende der Lynchjustiz im Amerikanischen Süden, 283 Hist. Z. 583, 590 (2006); Patricia Sullivan, Days of Hope 26-28(1996) (quoting a letter describing fingers and toes taken as souvenirs); James Clarke, Without Fear or Shame: Lynching, Capital Punishment and the Subculture of Violence in the American South, 28 Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 269, 269 (1998) (describing the 1899 lynching of Sam Hose in Palmetto, Georgia, where his ears, fingers, toes, and entrails were tossed or sold to the crowd of thousands).

[28] Manfred Berg, Das Ende der Lynchjustiz im Amerikanischen Süden, 283 Hist. Z. 583, 590 (2006) (trans.).

[29] Manfred Berg, Das Ende der Lynchjustiz im Amerikanischen Süden, 283 Hist. Z. 583, 584 (2006)

[30] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching In America: Confronting The Legacy Of Racialized Terror, 3d ED. 28, 62 (2017); Michael Pfeifer, Rough Justice 88 (Univ. Ill. 2006).

[31] Michael Pfeifer, Rough Justice 88 (Univ. Ill. 2006); Manfred Berg, Popular Justice: A History Of Lynching In America (2011).

[32] Manfred Berg, Das Ende der Lynchjustiz im Amerikanischen Süden, 283 Hist. Z. 583, 608 (2006)

[33] James Clarke, Without Fear or Shame: Lynching, Capital Punishment and the Subculture of Violence in the American South, 28 Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 269, 283 (1998).

[34] Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching In America: Confronting The Legacy Of Racialized Terror, 3d ED. 28, 63 (2017); James Clarke, Without Fear or Shame: Lynching, Capital Punishment and the Subculture of Violence in the American South, 28 Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 269, 283–85 (1998); Michael Radelet and Margaret Vandiver, 1986 Crime & Soc. Just. 94, 109 (1986).

[35] Death Penalty Information Center, Innocence Database, deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/innocence-database.

[36] Nat’l Registry for Exonerations, Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States 3 (Mar. 7, 2017), https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Documents/Race_and_Wrongful_Convictions.pdf.

[37] Brandon Garrett, et al., The American Death Penalty Decline, 107 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 561, 567 (2017).

[38] Ctr. for Contemp. Critical Thought, Abolition Democracy 4/13: The Abolition of Slavery at 1:00:11, YouTube (Nov. 12, 2020), https://youtu.be/hxgrp3ZxbBg?t=3611.

[39] CTV News, The Sister of Jacob Black makes a powerful statement on his shooting, YouTube (Aug. 25, 2020), https://youtu.be/qGm4jvqBJOo.