In March 2021, the Biden Administration announced a target of deploying 30,000 megawatts (MW) of offshore wind capacity by 2030, enough energy to power approximately 10 million homes. As of May 31, 2022, only 42 MW of offshore wind capacity was in operation, less than 1% of the Administration’s 30,000-MW target. While very few offshore wind projects have been completed, the U.S. Department of Energy has reported that projects comprising more than 40,000 MW of capacity are in the pipeline at various stages of development.

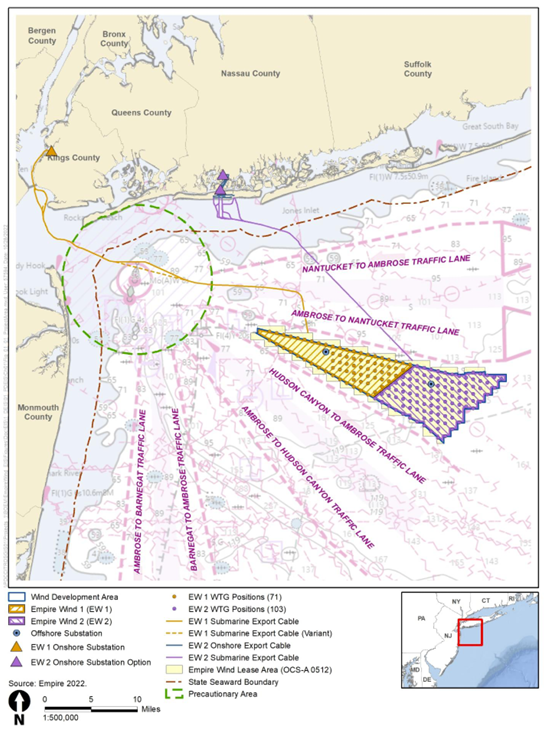

One such project is Empire Offshore Wind, which would add 2,086 MW of capacity to the country’s offshore wind portfolio, approximately 7% of the Biden Administration’s deployment goal. As proposed, Empire Wind would include up to 147 wind turbines more than 14 miles from shore in the shallow waters of the New York Bight between Long Island and New Jersey.

Caption: Empire Wind is divided into two sections, EW1 and EW2. The submarine export cable for EW1 would make landfall in Brooklyn, while the cable for EW2 would make landfall in Nassau County.

This week, the Sabin Center submitted comments on the draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) for Empire Offshore Wind. In those comments, we encouraged the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to fully analyze: (1) the climate change risks facing the project; and (2) the climate change risks facing marine mammals if the project does not move forward, including, in particular, the extent to which climate change poses a population-level risk to marine mammals.

First, we noted that the Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) new interim guidance explicitly directs federal agencies to “consider the ways in which a changing climate may impact the proposed action and its reasonable alternatives, and change the action’s environmental effects over the lifetime of those effects.” We further argued that considering climate change impacts is consistent with the federal government’s responsibility under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to attain the most “beneficial uses of the environment” without “undesirable or unintended consequences.” In light of these authorities, and to ensure that the project is appropriately designed to withstand the increasing impacts of climate change, we recommended that BOEM analyze the climate change risks facing the project as well as the project’s resilience to those risks under each of the alternatives being considered.

Second, we urged BOEM to analyze the extent to which the impacts of climate change, absent the project at issue, pose a population-level threat to marine mammals. As BOEM already acknowledges in the DEIS, “[w]arming and sea level rise could affect marine mammals through increased storm frequency and severity, altered habitat/ecology, altered migration patterns, increased disease incidence, and increased erosion and sediment deposition.” BOEM also finds that the project will result in a reduction of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that cause climate change. However, the DEIS does not address the extent to which marine mammal populations will be affected by climate change absent the project.

We noted that BOEM has performed this analysis in other environmental reviews, including, for example, by noting in the DEIS for Ocean Wind 1 that, absent the project, “[i]mpacts associated with climate change have the potential to reduce reproductive success and increase individual mortality and disease occurrence, which could have population-level effects.” BOEM has also previously noted in the final EIS for South Fork Wind that “populations that are already vulnerable, such as [North Atlantic Right Whale] may face increased risk of extinction as a consequence of climate change.” We argued that an analysis of the likelihood of population-level impacts to marine mammals absent the project is essential for BOEM to accurately establish the environmental baseline against which to evaluate impacts of the project. We further argued that, since a large-scale buildout of wind projects (including offshore wind) is a central element of the U.S. effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this analysis would help readers assess what would happen to marine mammal populations if this large-scale buildout does not occur.

Matthew Eisenson is a Senior Fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, where he leads the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative (RELDI).