On March 21, 2024, state regulators in Ohio approved the Oak Run Solar Project, an 800-megawatt (MW) solar generation project that will include 300 MW of battery storage, as well as 4,000 acres of crops and 1,000 sheep on site. This blog post will highlight key features of the project, as well as the opinion approving it, explaining: (a) what is important about the project; (b) who the key constituencies opposing and supporting it are; (c) how the Ohio Power Siting Board (Siting Board) decides whether to approve or deny solar projects; and (d) how the Siting Board decided that this project “will serve the public interest, convenience, and necessity,” as required for approval.

What Is Important About the Oak Run Solar Project?

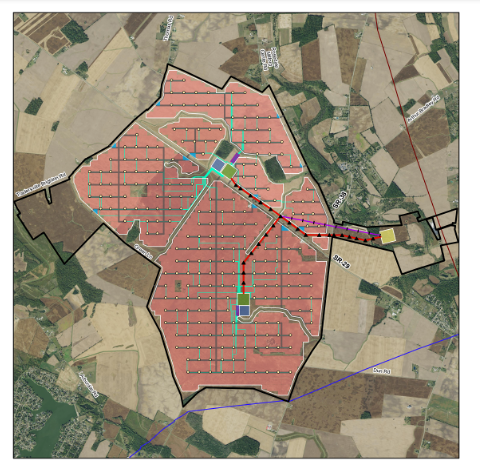

Oak Run is a solar-plus-storage project that will span 6,050 acres of private land in Madison County, Ohio. The project is an industry leader along three dimensions: generation capacity, battery storage capacity, and the incorporation of agrivoltaics (i.e., dual-use farming and solar generation) into project design.

First, with 800 MW of generation capacity, Oak Run is the largest solar generation project ever approved in Ohio. It will produce nearly three times as much power as the largest completed solar facility, Yellowbud (274 MW), and almost 40% more power than the next largest approved project, Fox Squirrel (577 MW).

Second, Oak Run’s 300-MW battery storage system is likewise the largest battery system ever approved in Ohio. No other approved system has a capacity greater than 200 MW.

Figure 1: Map of the Oak Run Solar Project area (Credit: Ohio Power Siting Board)

Third, and most importantly, Oak Run will be—by far—the largest agrivoltaics project in the United States. (Opinion ¶ 220.) The developer previously committed to including at least 2,000 acres of crops in the 6,050-acre project site. However, in the decision approving the project, the Siting Board set benchmarks that are even more ambitious. The decision stipulated that, after one year of operation, Oak Run must include 1,000 sheep and 2,000 crop acres; after eight years of operation, “at least 70 percent of the farmable Project Area, or 4,000 crop acres, shall contain agrivoltaics.” (Opinion ¶ 221.) For context, at the time of the evidentiary hearing on May 15, 2023, the largest agrivoltaics project in the country was Madison Fields (also in Ohio), where 150 acres of soybeans had been planted among rows of solar panels three days earlier. Before Madison Fields, the largest agrivoltaics project in the country was less than 5 acres.

Who Opposes Oak Run—and Who Supports It?

Like many projects across the country, Oak Run encountered local opposition. Opponents include three township boards of commissioners (the Townships), which issued resolutions against the project and intervened in the Siting Board proceeding to file testimony and briefs against it. The county board of commissioners also issued a resolution against the project and intervened in the proceeding, but it never submitted testimony or briefs. Opponents emphasized visual impacts (or, as they put it, “the inconsistency of the industrial solar facility with the rural character of the area”), as well as concerns about the loss of farmland.

Notwithstanding this opposition, Oak Run also found significant local support. The Sabin Center, through the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative (RELDI), partnered with Ohio attorney Trent Dougherty to help a local supporter named Dr. John Boeckl intervene in the Siting Board proceeding to advocate for approval of the project. As an intervenor, Dr. Boeckl submitted written testimony and two briefs (see his opening brief here and reply brief here) explaining why he supports the project. Others who intervened in support of the project were the local chapter of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), the Ohio Environmental Council, and Ohio Partners for Affordable Energy. Supporters primarily emphasized economic and environmental benefits of the project.

Others intervened without taking a stance on whether the project should be approved or denied. In particular, the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation and the Madison County Soil and Water Conservation District intervened for the more limited purpose of advocating for measures to protect agricultural soils, the farming industry, and water quality. In addition to those who formally intervened in the proceeding, state and local residents submitted at least 890 public comments expressing a wide range of views about the project.

How Are Solar Projects Approved in Ohio?

Solar projects in Ohio with a generation capacity of at least 50 MW and wind projects of at least 5 MW require approval from the state Siting Board. Smaller projects are permitted at the county level.

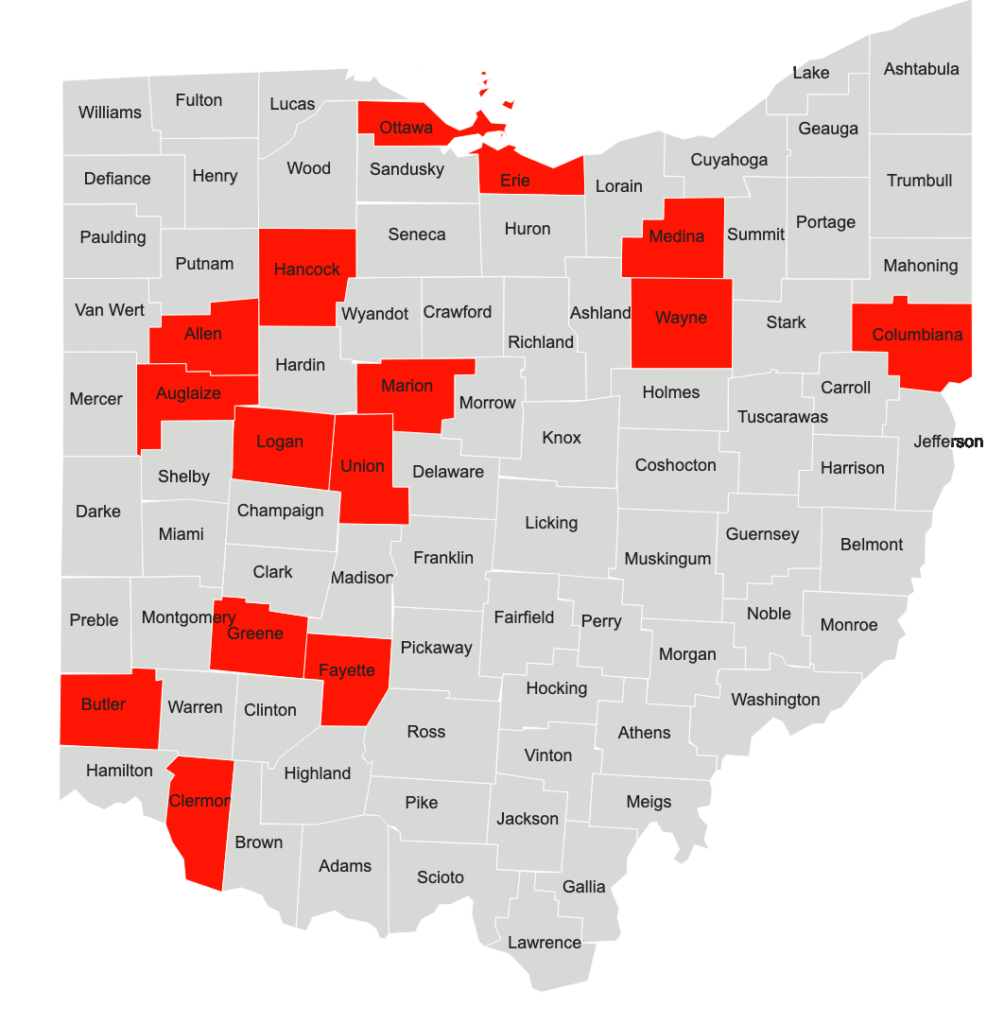

Renewable energy projects face significant disadvantages in the siting process compared to fossil fuel projects due to a three-year-old state law that allows counties to block large solar and wind projects—but not large fossil fuel projects. S.B. 52, enacted in 2021, empowers counties to block solar projects of at least 50 MW and wind projects of at least 5 MW by: (a) vetoing applications for individual projects; and/or (b) establishing restricted areas where any such project is prohibited. As shown below, at least 16 counties have now created restricted areas where solar is prohibited.

Figure 2: Ohio counties with restricted areas where solar projects of at least 50 MW are prohibited

Importantly, however, because Oak Run was already in the interconnection queue at the time S.B. 52 was passed, it is one of a dwindling number of projects that are “grandfathered in” to the Siting Board’s exclusive control and exempt from county veto or restrictions. The only provision of S.B. 52 that applies to Oak Run is the requirement to include two ad hoc voting members nominated by the townships and county among the nine voting members of the Siting Board.

To approve a project, the Siting Board must “find and determine,” in relevant part:

***

(2) The nature of the probable environmental impact;

(3) That the facility represents the minimum adverse environmental impact, considering the state of available technology and the nature and economics of the various alternatives, and other pertinent considerations;

***

(6) That the facility will serve the public interest, convenience, and necessity;

(7) [W]hat its impact will be on the viability as agricultural land of any land in an existing agricultural district …

(8) That the facility incorporates maximum feasible water conservation practices as determined by the board, considering available technology and the nature and economics of the various alternatives.

Ohio Rev. Code 4906.10(A).

What Is Significant About the Siting Board’s Opinion?

In its March 21 opinion, the Siting Board found that Oak Run satisfied all of the statutory criteria for approval. The most significant part of the decision was the Siting Board’s analysis of whether the project will “serve the public interest, convenience, and necessity,” a criterion that is notoriously opaque. Four key aspects of the Siting Board’s decision are particularly interesting.

First, despite the fact that all three townships and the county in which the Oak Run project is to be located issued resolutions against the project, the Siting Board found that opposition from local governments was not unanimous—and therefore did not compel rejection. For context, in a 2023 decision rejecting another project, the Siting Board held that “the unanimous opposition of every local government entity representing the area in which the Project is to be located is controlling as to whether the Project is in the public interest, convenience, and necessity.” Between October 2022 and January 2023, the Siting Board rejected a total of three solar projects on this basis, abruptly shifting gears after having approved 34 solar projects in a row since 2018.

In the Oak Run case, the Siting Board did not constrain its analysis to whether township and county commissioners had issued resolutions for or against the project. Instead, the Siting Board looked at how individual commissioners had voted, as well as expressions of support from other elected and appointed local officials. The Siting Board noted that the county commissioners were “consistently not unanimous” in their resolution against the project, explaining that one of the commissioners, Mark Forrest, had testified in support. (Order ¶ 226.) The Siting Board further noted that the project “received support from the elected President of the London City School Board, the Superintendent of London City Schools, the Treasurer and Chief Financial Officer of the Jefferson Local School District, the Superintendent of the Jefferson Local School District, and the Superintendent of Benjamin Logan Local School District.” (Order ¶ 226.) This holding shows that there is a high bar for opponents of a project to demonstrate unanimous opposition by local governments, and it is not sufficient merely to show that the township or county boards of commissioners issued resolutions against a project.

Second, the Siting Board examined the merits of the arguments for and against the project and found that many of the arguments against the project were uninformed and without merit. For example, in assessing the opponents’ argument that the battery storage system would be unsafe, the Siting Board explained that it “[did] not find evidence to support the Townships’ contention that the proposed [battery storage system’s] associated risks outweigh the benefits it presents.” (Order ¶ 227.) Specifically, the Siting Board found that the Townships’ concerns about bodily harm were unfounded in light of (a) the Townships’ concession that public exposure to lithium was unlikely as long as the battery system was properly maintained and (b) the developer’s commitment to comply with applicable regulations and industry best practices. (Opinion ¶ 227.) More generally, the Siting Board also found that “some local opposition . . . may not be fully aware of the commitments agreed to in the Stipulation and Application.” (Opinion ¶ 228). In reaching that determination, the Siting Board appeared to accept Dr. Boeckl’s argument that the Townships “failed to substantiate their opposition to the Project”—a point exemplified at the evidentiary hearing, when the Townships’ witnesses admitted on cross-examination “that they had not reviewed the Application and were unaware of conditions applicable to Oak Run.” (Opinion ¶ 213.)

Third, the Siting Board found that the project would have significant and long-lasting economic benefits, including providing $8.2 million of annual revenue to local government and schools. (See ¶ 222.) The Siting Board also noted that the project “is projected to create 500 or more electrical construction jobs and 63 long-term maintenance positions, in addition to long-term jobs that will be created by the agrivoltaics program.” (Opinion ¶ 222.) Here, the Siting Board appeared to accept Dr. Boeckl’s argument that the economic benefits of the project were “not temporary,” as the opponents had argued. (Opinion ¶ 204.)

Fourth, in rebutting concerns that the project would contribute to a loss of agricultural land, the Siting Board leaned on the agrivoltaics component of the project. The Siting Board found that “the dual-land use potential that agrivoltaics unlocks addresses a primary concern of Project skeptics: the conversion of land to a use other than agriculture.” (Opinion ¶ 220.) The Siting Board explained that beekeeping, planting crops between rows of panels, and grazing sheep would allow up to 70% of the farmable land to stay in production. (Opinion ¶¶ 220-21.) The Siting Board further concluded that “Oak Run’s strong commitment to agrivoltaics is additional evidence of Oak Run’s responsiveness to feedback from the local community.” (Opinion ¶ 221.)

In addition to addressing the ways in which the use of agrivoltaics mitigates concerns about the loss of farmland, the Siting Board emphasized the ambitious nature of the project (describing it as the “nation’s largest agrivoltaics project”) and the opportunity to put Madison County and the state of Ohio “at the forefront” of an “innovative” practice. (Opinion ¶ 220.) The Siting Board further emphasized the academic partnership with Ohio State University (OSU), noting that “[t]he collaboration between Oak Run’s sister company and OSU will not only improve the effectiveness of agrivoltaics at this Facility, but it will help to establish BMPs [best management practices] for the cultivation of crops alongside utility-scale solar operations, which will further benefit future projects in the state of Ohio and around the world.” (Opinion ¶ 220.)

Ultimately, the Siting Board concluded that, “as a total package, . . . Oak Run presents unique opportunities that would provide significant benefits to the state, which outweighs opposition that is nonunanimous on a local government level and some local opposition that may not be fully aware of the commitments agreed to in the Stipulation and Application.” (Opinion ¶ 228.) The Townships will have an opportunity to request a rehearing by the Siting Board and appeal to the Ohio Supreme Court.

Matthew Eisenson is a Senior Fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, where he leads the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative (RELDI).