By Sania Anwar

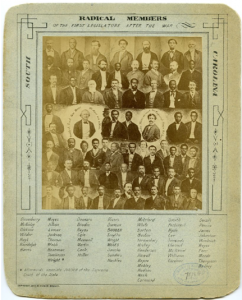

Radical members of the first legislature after the war, South Carolina.

Abolition is a reckoning. A reckoning so profound and exact, in creating and fulfilling the antithetical to what is dismantled, that it can offer redemption along with emancipation.

Eric Foner’s “The Second Founding” is the account of this nation’s post-Civil War constitutional reckoning – the beauty of redemption in its egalitarian promise, and the tragedy in its unfulfillment.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote of post-Civil War Reconstruction: “the slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

“The Second Founding” provides the historical account of the three Reconstruction amendments: Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution – “the most tangible legacies,” according to Foner, of the Reconstruction era, or that brief but monumental “moment in the sun.” It was, Foner says, “[the United States’] first attempt, flawed but truly remarkable for its time, to build an egalitarian society on the ashes of slavery.” It is a poetic claim, although ‘smoldering embers’ might be a more accurate status descriptor for slavery.

“The Second Founding” follows three decades after Foner’s seminal work, “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution,” a comprehensive study in analytical history of Reconstruction discussing the participation and contribution of the Black freedmen and freedwomen to the transformation of Southern Society in line with W.E.B. Du Boise’s thesis of Black centrality in “Black Reconstruction in America” (1935), the interconnectedness of racial attitudes and social and political development, the emergence of a purposeful and expanded national state for the ideal of a national citizenship, the economic and labor developments in the North, and the demise of Reconstruction through political compromises of 1877.

According to Foner, the Reconstruction era amendments were critical in creating the “world’s first biracial democracy.” The book is an ode to the emancipatory potential inherent in the promise of the amendments which “forged a new constitutional relationship between individual Americans and the national state.” For Foner, the profound change brought about by these amendments should be viewed as nothing short of a constitutional revolution, and therefore, a “second founding” during which, as Senator Charles Sumner declared, the federal government was for the first time deemed “the custodian of freedom.”

The book’s four chapters are methodically parsed out and trace the amendments’ path to ratification and their subsequent contested meanings and jurisprudential interpretation. The structure of the narrative can create the illusion of a linear progression to the values and issues being discussed. This is amplified by Foner’s decision to not include in this book – as he does in “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution” – the socio-economic experiential context of freedman and freedwomen during Reconstruction. But he warns early on that “history shows, progress is not necessarily linear or permanent [b]ut neither is retrogression.”

The efficient narrative reads not unlike an experience in theatrical immersion, a tragedy to be sure, where the plot lays bare, through well-researched public commentary and excerpts, the inner demons and struggles of men involved in the process of drafting and ratifying the amendments. It describes the contests and compromises over meanings and scope of consequential words such as ‘citizenship,’ ‘freedom,’ and ‘equality’ within the context of the characters’ own ideals, capacities, and prejudices, and their socio-political roles and motives.

The cast of characters features the speakers, legislators, abolitionists, and jurists involved in contributing to the construction and demise of Reconstruction amendments, including Republican abolitionists in Congress and the most frequent voices in the book: Wendell Phillips, John Bingham, Thaddeus Stevens, and Charles Sumner, the outlier in his unwavering commitment to egalitarian principles with a penchant for controversial[1] speeches; the various Black speakers, organizers, and abolitions often represented by the voice of the great orator, Frederick Douglass; the “incorrigibly racist” Andrew Johnson and his influence and political maneuverings; and the anonymous but powerful voice behind the Brotherhood of Liberty publication, Justice and Jurisprudence, offering valuable critique and alternative holdings of the Supreme Court rulings on the Reconstruction amendments. Although white women make a guest appearance within the context of women suffrage, voices of Black women, and the profound intersectionality of their perspectives, experiences, and identity, remain conspicuously absent.

The first chapter presents the historical account of the Thirteenth Amendment – the first amendment in the nation’s history, Foner notes, to expand the power of the federal government rather than restraining it. Its passage, according to Foner, began the Second Founding, and its ratification in 1865 brought about the “final, irrevocable abolition of slavery.” Lincoln’s proclamation – brought on in significant part for military and policy reasons – had ushered in military emancipation, and with the ratification of the amendment, military and legal emancipation “proceeded together.” Foner notes the “the depth and rancor of Democratic opposition” to the amendment but does not set aside much word count for the overtly racist polemics and remarks put forth in opposition.

Foner sets up the stage for the Fourteenth Amendment by a Sumner quote: “Liberty has been won. The battle for equality is still pending.” Surely it remains far from over today.

The meaning of ‘equality,’ ‘American citizenship,’ and ‘civil rights’ was debated at great lengths during the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and then again during the drafting of the Fourteenth Amendment. According to Foner, the Fourteenth Amendment was a plan to secure the guarantees contained therein for when the southern states were restored to the union, and it was also a “political document” serving as Republicans’ single-issue congressional campaign platform. Foner calls the election of 1866 “the closest thing American politics has seen to a referendum on a constitutional amendment” ushering in the remarkably overlooked and misrepresented period of Radical Reconstruction – “the experiment in interracial democracy known as Radical Reconstruction.” Through the Reconstruction Act of 1867, the new southern governments adopted constitutions that attempted to create the framework for democratic and egalitarian societies. During this period, Foner identifies the earliest arguments for incorporation of the Bill of Rights to be applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, a belief deemed “a virtually uncontroversial minimum interpretation of the amendment’s purposes” for the Republicans. This notion was subsequently nullified, at least through the amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause, by the Supreme Court and resurrected again gradually during the “rights revolution of the twentieth century” via the Due Process Clause.

Today, the significance of the Fourteenth Amendment in constitutional jurisprudence remains uncontroverted. In carrying forward the tradition of revolutionary constitutional expansion, where the Thirteenth Amendment served as the first to expand federal authority, the Fourteenth Amendment was the first to elevate “equality to a constitutional right of all Americans.” But what did “equal protection” mean, what did it offer, and did it offer protections against actions of private actors? What were the attributes of national citizenship? The Supreme Court would continue defining and interpreting the meanings of rights incorporated within the guaranteed of these amendments to this day, rarely for the benefit of Black Americans.

The ratification of Fourteenth Amendment was met with little elation in 1868, writes Foner, as it was seen as a weak compromise in setting aside the provision for black suffrage. Despite the passage of the Reconstruction Act of 1867 during Radical Reconstruction, many black men still remained without the right to vote. Foner attributes the “rapid evolution of rights consciousness” during Reconstruction for the increased acceptance of Black men’s suffrage as the logical extension or part of abolition of slavery. But few states supported surrendering that power to the federal government.

As Foner lays out, the debates and the movement for the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment brought out the “limits of western Republicans’ egalitarianism” by exposing prejudices against various other groups, especially Irish Catholic – the “minions of despotism” according to one Senator – and the Chinese immigrants. Typical of the zero-sum view of rights in a non-egalitarian system, voter, Black men’s suffrage was negotiated within the exclusion of other groups, including women. Foner writes that the campaign of 1868 brought with it “the most overt appeals to racism in American political history” and this “internal disunity” of the Republican Party in its asynchronous group-based prejudices contributed to its complicated path to passage in 1869. In the end, a weaker version was adopted, not from a lack of support for Black male suffrage, says Foner, but from the “opposition to equality for others.” This would ultimately prove to be a “disastrous miscalculation” which failed to anticipate and protect against the proliferation of disenfranchisement of Black Americans through over a century and a half.

Enter, stage right, the Supreme Court.

The final chapter, the climax of this tragedy, begins with the abandonment of Reconstruction and the battle over the meaning of its legacy amendments. The post-election political compromises of 1877 resulted in withdrawal of federal troops from the south and the Democratic control of the southern states. Foner traces the retreat from the ideals and promises of Reconstruction in various Supreme Court holdings, attributing the abandonment to both “judicial racism but also to the persistence of federalism.”

The issues related to the amendments before the Supreme Court were of meanings, scope, and purpose of the amendments’ guarantees. Did the Thirteenth Amendment include protections against the “badges and incidents” of slavery, and if so, what were they? Did the amendments’ protections apply to “public rights” such as rights to public accommodations and against violations by private actors? Were laws that were race-neutral on their face yet designed to achieve discrimination or interference with right to vote invalid?

In the years and decades that followed, the Supreme Court’s constitutional jurisdiction significantly abrogated the egalitarian and emancipatory guarantees of the amendments with respect to Black Americans. It did so by rejecting claims of inequality classified as “badges and incidents of slavery,” by nearly nullifying the promises of the Privileges or Immunities provision, by distinguishing between civil and social rights, by refusing to invalidate state disenfranchisement measures, and by limiting its scope for reviewing discrimination or violations of constitutional protections by private actors. Foner does not hold back in attributing another cause in the Supreme Court’s abrogation of constitutional guarantees: deficit of intellect. With the exception of the few talented jurists, he writes, most of the twenty-four men who served on the Court between 1870 and 1900 were “mediocrities.” This mediocrity still championed white supremacy, a belief further strengthened by the country’s “imperial adventures” in the Spanish-American War, and the implementation of the vicious Jim Crow system.

According to Foner, the Warren Court’s decisions in the 1950s and 1960s – a period Foner calls the “Second Reconstruction” – finally provided the reinvigoration of the Reconstruction amendments. However, the denouement of this entire saga – and one in which we as the audience are participating today – is the ongoing abrogation of the democratic principles of Reconstruction.

Whether intentional or not, irony is a recurring theme in the book. It begins with Foner’s connection with the Dunning School through Columbia University, and ends with the final words of the book, urging Americans to “return to the nation’s second founding and find there new meanings for our fractious and troubled times.” How complete was a founding which remains lost to those for which it was sought? Does the word “Second” indicate potential for a third? Was the ‘Founding’ in the title of the book meant to be a noun – designating the period in time and constitutional history – or is it a verb indicating a process that will remain perpetually unfinished, a direction to be travelled?

Foner acknowledges the fraught historiography of Reconstruction, the “politics of history,” and the crucial role played by the account of Reconstruction developed by Professor William A. Dunning of Columbia University and his students. The Dunning School’s scholarship condemned Reconstruction and provided the academic, legal, and intellectual foundation for Supreme Court jurisprudence limiting the guarantees of Reconstruction amendments, Jim Crow, and the Lost Cause ideology of the South – depicting a benign and nostalgic view of slavery and the saving of the South by white supremacists following the failed Reconstruction. In “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution” (1988), Foner notes the irony of his original research on Reconstruction – which dismantled the erroneous historiography of the Dunning School – and was partly covered by the Department of History’s Dunning Fund at University of Columbia.

But the Dunning School itself developed on an ironic perch of academic standing. In support of introducing an amendment abolishing slavery in 1863, congressional representatives had relied on a proposal presenting a draft of seven amendments developed by Professor Lieber of Columbia University. According to Foner, Lieber’s ideas and writings had influenced the passage of both the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. In 1903, Dunning was appointed the Francis Lieber Professor of History and Political Philosophy at Columbia University, and it was from this academic pulpit that he developed the Dunning Scholarship.

The Second Founding reveals how the unanticipated subversion of the guarantees provided in Reconstruction amendments were built upon the very language of the amendments – language decided mostly on compromises made to promote acceptance, or in one situation, to allow for timely dinner.[2] The irony in constitutional enshrinement of rights and guarantees is that it invites interpretation of the limits and confines of such rights.

The Thirteenth Amendment, seeking to end slavery, allowed involuntary servitude to survive as a punishment for crime. This sounded the constitutionally sanctioned death knell for “the brief moment in the sun” of the freedman and freedwomen and their generations to come, through convict leasing and involuntary prison labor in today’s increasingly carceral system.

The second section of the Fourteenth Amendment provided a penalty for restriction on voting rights of men, but not women. Not only was the penalty never enforced in favor of Black suffrage, it introduced a gender distinction for the time in the Constitution and further delayed suffrage for women. This sowed further division between the suffrage and abolitionist movements. The division and strife would get deeper during the legislative and rhetorical battle over the Fifteenth Amendment.

The Fifteenth Amendment, in failing to provide a positive guarantee of enfranchisement, left itself vulnerable to circuitous interpretations which resulted in proliferation of laws disenfranchising most Black people without explicitly relying on race.

The reader, as the audience to Foner’s account of the amendments’ grand egalitarian promise, can appreciate the dismaying irony provided by his critique of the Supreme Court decisions abrogating and nullifying the amendments’ guarantees. The Supreme Court was more willing and more creative in its interpretations to extend protections to corporations rather than the Black people. During the Jim Crow period, Foner writes, the Supreme Court had a full docket of cases invoking the Fourteenth Amendment – but almost every single one of the cases sought liberty for corporations. The Court employed “a state-centered approach in citizenship matters and a nation-centered approach in affairs of business,” and felt it a legitimate interpretive exercise to extend the protections of the Due Process Clause to corporations as legal “persons” and yet at the same time deny similar protections to Black personhood.

“Ironies abounded” Foner says, in the Slaughterhouse Cases, where those who sought an expansive interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment were whites.

Even modern-day Supreme Court jurisprudence, Foner notes, has proved more sympathetic to white plaintiffs claiming reverse discrimination in affirmative action than to the continuing “badges and incidents” of slavery and the legacies of Jim Crow and convict leasing.

Finally, no jurisprudential doctrine is more infused with irony than the phrase ‘separate, but equal’ from the now infamous 1896 Plessey v. Ferguson case, where the Court denied the constitutional challenge to accommodation of a Black man in a whites-only train car by noting the white race as the “dominant race” and yet holding that as long as facilities were equal, separation was not “a badge of inferiority,” even if the “colored race” chose “to put that construction upon it.”

Sometimes, irony can be more delicious than tragic. Such was the case in Foner’s account of the Taney inkstand. Justice John Marshall Harlan had in his possession the inkstand which Roger B. Taney had presumably used in writing the Dred Scott decision in which the Court had held that a slave could not be a citizen. The Civil Rights Cases made their way before the Court in 1883, comprising of five cases alleging violations of Civil Rights Acts of 1875 arising from denials of public accommodations to Black people. The Court refused to apply the Fourteenth Amendment to private owners. Harlan dissented. While deliberating over the decision, Harlan had suffered from writer’s block in drafting his now famous dissent. His wife, Malvina Harlan, a connoisseur of irony,[3] found and placed the inkstand on his desk, which inspired him to write his dissent and to emerge in his role as ‘The Great Dissenter.’ “It was, I think, a bit of ‘poetic justice’” writes Malvina Harlan in “Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854-1911” (2002), “that the small inkstand in which Taney’s pen had dipped when he wrote that famous (or rather infamous) sentence in which he said that ‘a black man had no rights which a white man was bound to respect,’ should have furnished the ink for a decision in which the black man’s claim to equal civil rights was as powerfully and even passionately asserted as it was in my husband’s dissenting opinion in the famous ‘Civil Rights’ case.”

“Here is a profound irony,” writes Foner, that the Fourteenth Amendment – which avoided language providing for black suffrage, but guaranteed the fundamental rights for citizens in a democracy – would never have passed but for the votes of Black men in southern elections and legislatures. This year’s election and its turnout and results have established the continuing relevance of Du Boise’s poetic words: “Democracy died save in the hearts of black folk.” Time and time again, democracy is saved by those whom it continues to fail.

The tragedy of Reconstruction comes not from its defects but from the failures in acknowledging, fulfilling, and furthering its promise. “If the era was tragic,” says Foner, “it was not because it was attempted but because in significant ways it failed, leaving to subsequent generations the difficult problem of racial justice.” For all the misfortunate in the denied potential of Reconstruction, Foner urges hope throughout. The issues central to Reconstruction, he writes in “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution” (1988) are “as old as the American republic, and as contemporary as the inequalities that still afflict our society.” A century and a half after the ratification of the Reconstruction amendments, the promise of equality remains unfulfilled. In support of his optimism, Foner identifies the use of the amendments as constitutional foundation for the civil rights revolution. We are still trying to work out “the consequences of the abolition of American slavery,” he writes, and in that sense, “Reconstruction never ended.”

In an echo of the fateful election of 1876, the nation is currently trying to grapple with the limits of its democratic institutions with a President who has refused to concede. “Reconstruction history has always been morally inflected,” says Foner “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution” (1988), because writing about the period stands in relation to key problems of our own time. Problems of our own time certainly depict democracy and morality in crisis. But it is hardly unprecedented.

“The most magnificent drama in the last thousand years of human history” writes Du Bois “was the transportation of ten million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent into the newfound Eldorado of the West: They descended into Hell; and in the third century they arose from the dead, in the finest effort to achieve democracy for the working millions which this world had ever seen. It was a tragedy that beggared the Greek; it was an upheaval of humanity like the Reformation and the French Revolution. Yet we are blind and led by the blind.”

Will this nation allow itself the humility of reckoning with the incomplete abolition of slavery and its legacies and give way to the egalitarian promise through the “unused latent power” of the Reconstruction amendments?

It remains to be seen.

And to be found.

Notes

[1] In 1856, Charles Sumner was attacked in the Senate Chamber by a South Carolina Democrat who used his walking stick to beat and seriously injure Sumner. Earlier, Sumner had condemned the pro-slavery senator using charged language in his “Crime Against Kansas” speech. United States Senate, The Caning of Charles Sumner, May 22, 1856 www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm.

[2] In the book, Foner notes Charles Sumner’s regret in allowing the criminal conviction exception – the ultimate tool for abrogating the very freedom guaranteed by the Thirteenth Amendment – in the wording of the Thirteenth Amendment: he had hoped to propose eliminating the clause regarding convicted criminals but failed to act because his colleagues were anxious “to get their dinner.”

[3] In a twist of serendipitous fate, the story of the inkstand comes from Malvina Harlan’s memoirs which were first unearthed by another Great Dissenter, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, from the Library of Congress during her research for a lecture on the wives of prior Justices.