By Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

I am writing from Ghana, the old Gold Coast, one slim state away from Dahomey, famous for its woman soldiers and brass art, the area from where the largest number of people were put on the middle passage to be enslaved in the United States for cotton, in the Caribbean for sugarcane, and the rest of the European world for various other kinds of forced labor. We remember the infamous apocryphal complaint of the Asante Queen Osei to Queen Victoria about suspending the slave trade as an unnecessary economic loss.

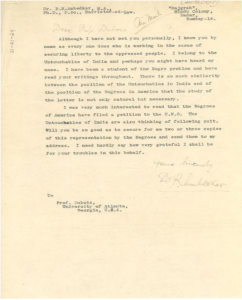

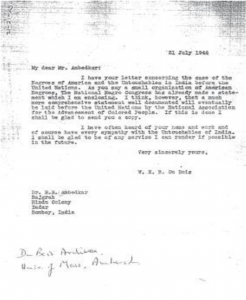

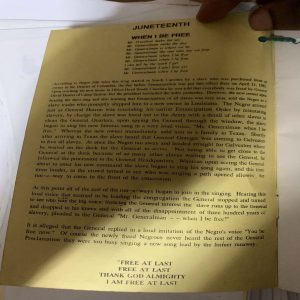

Today is Juneteenth, 19th June, the date when, in 1865, General Granger undid the attempts in the American South to rescind the Emancipation, and declared freedom, once and for all, in Galveston, Texas. I write in the name of my recently deceased friend, the great poet Sankha Ghosh, who wrote movingly of a poem mourning the murder by police in Soweto of a 12-year-old girl-student protesting Afrikaans, on 16th June, 1976. Sankha connects it to the police murder of a 16-year old woman who had joined a demonstration against hunger in the city of Kuch Bihar, in 1951. Sankha Ghosh rewrites a traditional bride-figure from Bangladesh as these two women, writing, in my uncertain translation, that she “crafts her wedding-night with gunpowder in her breast.” In the accompanying essay he writes, again translated by me, “In all lands, at all times, oppression arrives with the same ways and means, as if to build a bridge from one end to the other.” How did he figure intersectionality in 1976? As an Indian, I write in the name of W.E.B. Du Bois, and in the name of B. R. Ambedkar, who wrote to Du Bois in 1946 to annihilate the caste system.

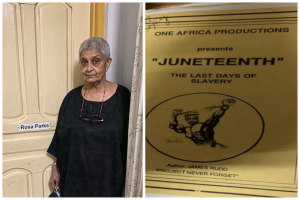

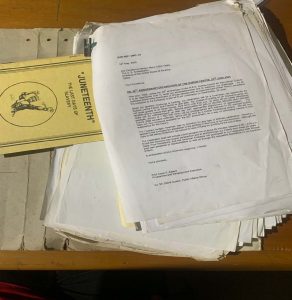

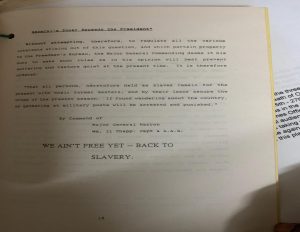

I write from the Marcus Garvey Guest House, on the compound of the W.E.B. Du Bois Centre for Pan-African Culture in Accra, where – among the papers stored in Du Bois’s small, last, core collection, that he brought with him when he came to settle in Ghana in 1961, at the age of 93, harried by McCarthyism, at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah, the first Prime Minister and President of independent Ghana – there is a wonderful stack of papers, citing the programs undertaken at the Centre in the more recent years, inside which is tucked a pamphlet on Juneteenth.

Today is Saturday, and there is no administration at the Centre. But there is, as it happens, a community market, which I hope to photograph, after finishing these remarks. There is a projector in the museum, and every instrument for producing and projecting a little document like this one. I have only a small laptop. If I can somehow show this to the vendors at the market, I will have acted as a neighbor, since I live within walking distance of the apartment on Edgecombe Street on Silver Hill in New York where Du Bois lived for some years; and acting again as a neighbor, standing a few feet away from the mausoleum where his body is laid to rest.

I cite a couple of pages from Juneteenth in closing.

The “run-a-way” slave, General Butler’s “contraband,” the ones who undertook what Du Bois called a “General Strike,” downing tools at the plantation, joining the Union Army, changing the Civil War, from one to keep the country together to one to free the enslaved – “self-liberators” (David Roediger). And following them, standing on that bridge of oppression evoked by Sankha Ghosh, repaying ancestral debt as a caste-Hindu, I raise my voice to join the cry that has still not been fully achieved in the world: “Free At Last!”

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Accra/New York

© Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak