By Brandon Vines

“You can do what we ask you to, or you can suffer the consequences.”

– Kentucky sheriff’s deputy Kevin Sumner[1]

This seminar series focuses on the concept of “Abolition Democracy”—that is, the combination of the negative act of abolition with the positive act of crafting more equitable replacements.[2] To envision how Abolition Democracy might apply to the police, it is imperative to first understand the social roles filled by modern police forces.

This essay isolates one such raison d’être of modern policing: enforcing formal discipline. This essay will, first, discuss the form and function of police-imposed discipline and, second, identify the role of formal discipline in Alex Vitale’s book, The End of Policing. Particular attention will be paid to the disparate impact of repressive disciplinary functions along racial, gender, and class lines.

An Obsession with Formal Discipline

The idea that police enforce discipline, usually with a moralized undertone, runs through Vitale’s The End of Policing. Vitale often emphasizes that this discipline is not so much intended for the benefit to the recipient but, rather, for the creation of the appearance of compliance with the prevailing social order. I’ll refer to this façade as formal discipline.

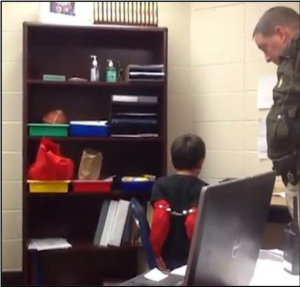

Formal discipline is most readily identifiable in extreme police responses to relatively minor provocations. The following three examples are illustrative. First, the sheriff’s deputy quoted at the beginning of this essay was a part-time elementary school resource officer. In this role, Deputy Sumner was monitoring a 54-pound third grader with ADHD and PTSD, who earlier physically lashed out against school staff. The child attempted and failed to hit Sumner, who responded by placing the child in handcuffs. The child was so small, he had to be hand cuffed around his biceps, and was recorded saying “Oh, God. Ow, that hurts.” The same year, Sumner handcuffed a nine-year-old girl who also has ADHD. The families of both children left the school district and reported their children suffered nightmares, began bed-wetting, and would not let their mothers out of their sight.[3]

Second, Derecka Purnell describes a shooting she witnessed by a security guard at a recreation center. A boy skipped a sign-in sheet before heading to the basketball court. The guard, angry at the infraction, stormed in and shot the boy in the arm.[4]

Third, an officer tasered an elderly man to the point of hospitalization for lacking a registration sticker on his license plate. The elderly man was attempting to summon his boss at the car dealership to explain dealers’ plates were exempt from the requirement. “In the subsequent inquiry, the officer insisted that the man’s passive resistance was a threat that had to be neutralized.”[5] These cases are not unique, but they show how visible breaches of the decorum of formal discipline, even passive ones, are a perceived threat.

Deputy Sumner and the handcuffed child (source).

Foucault offers some insight into the role that the maintenance of formal discipline plays in society. Formal discipline effectively punishes people not for their actions but for who they are. It is an attempt by society to “correct” those who do not conform to expectations through what Foucault called a “moral orthopedics,” that is, the use of strict corrective measures and pervasive regulation of minutiae to form a docile population. By the eighteenth-century, “police added a disciplinary function to its role. . . it was a complex function, since it linked the absolute power of the monarch to the lowest levels of power disseminated in society.”[6] The police extend discipline, and thus impose power, upon the most minute and disconnected elements of society.

While addressing prisons, the following passage from Foucault’s book, Discipline and Punish, casts light on the disciplinary function of police in society:

“[T]he art of punishing…brings five quite distinct operations into play: [(1)] it refers individual actions to a whole that is at once a field of comparison, a space of differentiation and the principle of a rule to be followed[; (2)] differentiates individuals from one another, in terms of the following overall rule: that the rule be made to function as a minimum threshold, as an average to be respected or as an optimum towards which one must move[; (3)] measures in quantitative terms and hierarchizes in terms of value the abilities, the level, the “nature” of individuals[; (4)] introduces, through this “value-giving” measure, the constraint of a conformity that must be achieved[; and (5)] traces the limit that will define difference in relation to all other differences, the external frontier of the abnormal.”[7]

Plates from Discipline and Punish depicting orthopedics (left) and a prison lecture on the evils of alcoholism (right).

The cumulative effect of these five operations is to “normalize.”[8] In the modern United States, I argue, normalization in the context of formal discipline means policing to enforce the external appearance of the “norm,” namely whiteness, heterosexuality, and middle-class respectability.[9] In this way, modern policing has something of a panoptic[10] role, particularly visible in broken-windows policing. The result is an internalized surveillance and otherizing of highly policed areas. The paradox, of course, is that, like incarceration, the imposition of formal discipline fails to prevent crime. This is not simply an error, but instead the full realization of the police’s role in the perpetuation of economic, racial, and gender inequities.[11]

Beyond the realm of theory, formal discipline has a profound and damaging human impacts. The remainder of this essay will review formal discipline’s practical role through the lens of two chapters of The End of Policing.

Educational Discipline

The End of Policing’s third chapter details the School-to-Prison Pipeline, where the police’s goal is not to prevent educational failure but to otherize and expel those who do not conform to arbitrary standards of decorum and performance. Approximately a quarter of American schools have a police officer assigned to them whose work involves disciplining students.[12] These officers do not serve an ameliorative role, but, instead, primary perform an exclusionary role.

High-stakes testing has created a further incentive to push students out. Vitale describes how as test scores increasingly determined school funding, schools focused on zero-tolerance disciplinary approaches. The result is abandoning “problematic” students under the guise of a policy of deterrence. To deal with millions of suspensions, for-profit “supermax schools” were developed with intensive disciplinary and surveillance systems. Predictably, underpaid teachers and a hyper-controlled environment led to terrible outcomes for students. One charter school had a “got to go” list aimed at removing students who did not match school disciplinary rules. The result is children who need the support of schools the most. Children like the handcuffed third grader with ADHD and PTSD described above, are further marginalized.

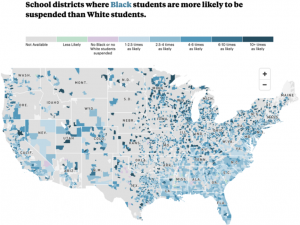

Nearly every America school where there is data suspends

black students far more frequently than white students. (source)

Disciplinary action disproportionately falls on students who are non-white, live in “non-traditional” or low-income homes, grapple with mental illness, are undocumented, or are gender non-conforming.[13] Nationally, black students are 3.9 times more likely to be suspended than white students.[14] According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, between 2006 and 2014, disciplinary officers sprayed 199 students with a painful combination of tear gas and pepper spray. All those sprayed were African American and one was pregnant.[15]

Sexual Discipline

The End of Policing’s sixth chapter details policing sex, where the police’s goal is not to protect sex workers, but to otherize and remove sex workers from view. The police enforce distinctly middle-class heteronormative expectations of sexual “decency.” This expected formal discipline manifests in how sex crimes are treated, with the end result being that sex work is driven underground where the control of pimps and threat of horrific abuse dramatically increases.

While decriminalizing sex work has its pitfalls, the police cause far more harm both directly through police violence and indirectly by driving sex workers underground. The federal government, unprompted by any user complaints, raided and shut down the office of Rentboy.com, where mostly male sex workers posted ads. Recent legislation[16] has virtually banned sex workers from advertising online and confined them to more dangerous business models, like relying on pimps.

Vice policing directly harms vulnerable populations. Police tactics involve raids and policing “known prostitution zones,” and police consider the possession of condoms, a past arrest record, or transgender appearance as sufficient evidence for arrest and prosecution. Criminalizing condoms forces sex workers to choose between short-term harm from police and long-term harms from exposure to sexual transmitted infections. Gender non-conforming people and people of color are more likely to be arrested. Finally, criminalization leaves sex workers without legal recourse if they are raped, beaten, or otherwise victimized.

Vitale explains that residents and business owners couch their complaints of sex work in moralistic terms. Police similarly describe sex work in highly moral terms, which minimizes the autonomy and humanity of sex workers. This morality manifests most directly in enforcement of a formal discipline that reflects whiteness, heterosexuality, and middle-class views of decency. For example, Vitale explains that in strip clubs, police typically enforce vague laws dictating “community standards,” that often reflect the moral standards of a certain portion of the community.

Most reform efforts are continuations of this moralizing. Some jurisdictions allow clients to be diverted from prosecution to “john schools,” where the stern lectures have a moralizing bent. Other focus on pressuring sex workers to leave the trade, reducing sex workers to the two-dimensional role of a victim without addressing the fundamental pressures and autonomous choices that lead sex workers to the trade in the first place. “As long as women and LGBTQ people are poor, socially isolated, and lack social and political power; as long as runaway and “throw away” kids have no place to turn but the streets, they will be at risk of trafficking and coercion. Neither the police nor the “rescuers” seem keen to address these social and economic realities.”[17] In short, the role of police in sex work does not uplift communities but, rather, enforces a formal discipline intended to remove sex workers from sight.

Conclusion

By imposing formal discipline on sex and education, the coercive force of the state is sanctioning a form of morality. Enforcement of this formal discipline is aimed not only at conversion, but also at exclusion. This othering facilitates the systemic violence and incarceration that too often follows. With this in mind, “[i]s it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?”[18]

This essay has focused on how enforcing formal discipline is one function modern police use to perpetuate the status quo. Implementing Abolition Democracy would mean not just ending this imposed discipline, but replacing it with equitable structures that empower their communities. While beyond the scope of this essay, the answer may well lie in democratization and community autonomy. Ethics should be a collaborative process between the individual and members of their community, not an imposition from an outside elite. As Alex Vitale writes, “We don’t need empty police reforms; we need a robust democracy that gives people the capacity to demand of their government and themselves real, nonpunitive solutions to their problems.”[19]

Notes

[1] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 3 (Verso 2017); see also Kentucky Sheriff To Pay $337k For 2014 Handcuffing of Children in Elementary School, ACLU-KY (Nov. 5, 2018), link.

[2] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 1 (Verso 2017); see also Angela Davis, Abolition Democracy 91 (Seven Stories Press 2005) (“In order to achieve the comprehensive abolition of slavery—after the institution was rendered illegal and black people were released from their chains—new institutions should have been created to incorporate black people into the social order.”). For a review of these ideas, see Abolition Democracy 2/13 on this website, link.

[3] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 3 (Verso 2017); Kentucky Sheriff To Pay $337k For 2014 Handcuffing of Children in Elementary School, ACLU-KY (Nov. 5, 2018), link; Opinion and Order, S.R. v. Kenton Cnty. Sheriff’s Off., No. 2:15-cv-143 (WOB-JGW) (E.D. Ky 2017), link.

[4] Derecka Purnell, How I Became a Police Abolitionist, Atlantic (July 6, 2020), link.

[5] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 1 (Verso 2017)

[6] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish 214–15 (Second Vintage Books ed. 1977).

[7] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish 182–83 (Second Vintage Books ed. 1977).

[8] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish 183 (Second Vintage Books ed. 1977).

[9] For a much more detailed treatment of a similar argument, see Andrew Johnson, Foucalt: Critical Theory of the Police in a Neoliberal Age, 141 Theoria 5–29 (2014).

[10] Designed by Jeremy Bentham, a Panopticon (Greek for “all seeing”) is an institution designed with a tower in the center, allowing surveillance into each cell. For Foucault, the Panopticon internalizes a permanent sense of being observed and scrutinized. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (Second Vintage Books ed. 1977).

[11] See, e.g., Amna Akbar, An Abolition Horizon for (Police) Reform, 108 Cal. L. Rev. 101, 118 (2020) (forthcoming) (“Police are a conduit of segregation, gentrification, and displacement, creating and maintaining spatially and racially concentrated inequity…Police move people ‘and economic resources in and out of place, enact[] borders. . . and reconfigure[] opportunities and various social structures (housing, schools, public transportation, parks) in ways that reproduce racial inequity.’”).

[12] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 3 (Verso 2017) (“Over 40 percent of all schools now have police officers assigned to them, 69 percent of whom engage in school discipline enforcement. . . .”).

[13] See DIGNITY IN SCHOOLS CAMPAIGN, WHY COUNSELORS, NOT COPS? (2018) (cited by Akbar, supra note 11, at 148), https://dignityinschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WhyCounselorsNotCops.pdf.

[14] Lena Groeger, Annie Waldman & David Eads, Miseducation, ProPublica (Oct. 16, 2018), link.

[15] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 3 (Verso 2017).

[16] The Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA), Public Law 115–16 (2018).

[17] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 6 (Verso 2017)

[18] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish 228 (Second Vintage Books ed. 1977).

[19] Alex Vitale, The End of Policing Ch. 1 (Verso 2017).