By Bernard E. Harcourt

Michel Foucault identified in the Iranian uprising of 1978 a modality of religious political revolt and a form of political spirituality that privileged, in the secular realm, expressly religious aspirations. What Foucault discovered in Iran was, in his words, a political spirituality: a mass mobilization on this earth modeled on the coming of a new Islamic vision of social forms of coexistence and equality.

Foucault described the mass mobilization in Iran as an Islamic uprising. He did not minimize in any way its Islamic religious foundations or modes of expression. On the contrary, Foucault framed the uprising through the lens of Ernst Bloch’s thesis, in The Principle of Hope (3 vols., 1954-1959), on the rise, in Europe, from the twelve to the sixteenth century, of the religious idea that there could come about on this earth a form of religious revolution (see Foucault, There Can’t Be Societies without Uprisings, interview with Farès Sassine, August 1979). Foucault related the events in Iran to this religious model, originally formulated by dissident religious groups in the West at the end of the Middle Ages—and which Foucault referred to as “the point of departure of the very idea of Revolution.” (Ibid.).

Foucault explicitly characterized the will of those Iranians in revolt with whom he had contact as taking the form of a “religious eschatology”—not the form of a quest for another political regime, nor in his words for “a regime of clerics,” but instead for a new Islamic horizon. (Sassine interview, 4) When those in revolt spoke of an Islamic government, Foucault maintained, what they had in mind were new social forms based on a religious spirituality, sharply different than Western models. (Sassine interview, 5-7) Foucault pointed to Ali Shariati as the thinker who had most clearly posed the problematic and formulated this vision. (Sassine interview, 10)

It is to this model of uprising as political spirituality, this modality of religious political revolt that we turn to in Uprising 6/13. By contrast to the modality of revolt that we discussed during our seminar Uprising 3/13 on the Arab Spring, the modality of revolt that Foucault identified in Iran in 1978-79 was expressly and primarily religious. Much (but of course not all, as evidenced once again by subsequent events) of the ideological wellspring in Tahrir Square was more secular, leaderless, and occupational: a form of disobedience against a secular authoritarian regime—at least as portrayed in much of the reportage and documentaries like Tahrir: Liberation Square, directed by Stefano Savona (2012). The situation was very different in 1978 Iran, at least on Foucault’s assessment. And it gives rise to a different modality of revolt: a religious eschatological modality of uprising.

~~~

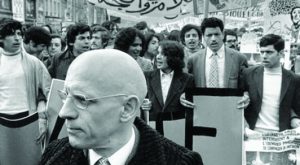

In 1978-79, Foucault published a series of long-form essays, part editorial, part reportage, in the Italian newspaper Corriere della sera regarding the uprising in Iran. His first editorial, “The army, when the earth quakes,” was published on September 28, 1978, after he returned from his first trip to Iran from September 16 to 24, 1978. By that time—by the end of September 1978—martial law had already been declared in Iran, following several months of uprisings and the brutal repression and mass murders of demonstrators by the Shah’s army. Foucault published another five essays in October and early November, before returning to Iran from November 9 to 15, 1978. After that second trip, Foucault published three more essays in the Corriere della sera, the final one appearing on February 26, 1979. By that time, the Shah was deposed, having left for exile mid-January 1979, Khomeini had returned to Teheran and formed a new government, and Mehdi Bazargan was heading the country. Only a month later, at the end of March 1979, the country voted by referendum for an Islamic republic. Foucault published his last intervention on Iran, a capstone editorial in Le Monde, titled “Useless to revolt?,” on May 11-12, 1979. Foucault also gave several interviews over the period, and engaged in other debates, with a final interview in August 1979.

From the opening essay (“The army, when the earth quakes,” Sept. 28, 1978), practically in the first opening paragraph, Foucault identified Islam as the symbol, node, and magnet for power resistance to the Shah. The Shah, on one side, is represented by terms such as “the administration,” “the government,” “the ministry,” “the official plans,” and simple “the power” [le pouvoir]; and is associated with “the notables” and the United States (D&E3 #241, 664, 668-69). The US, which restored the Shah to power, is portrayed as the dominating force in Iran—with 30 to 40 thousand American advisers to the Shah’s army, pervasive American military equipment, and the imposition of an American order in Iran. As a high military official, in the opposition, confided to Foucault, “the Americans dominate us.” (668)

The other pole is “l’islam”—Islam: “Facing the government and against it, Islam: for ten years already.” (664). Islam is symbolically represented by that “cleric,” an anonymous cleric (not Khomeini, who does though already appear in the next paragraph), who leads and organizes the “artisans” and “farmers,” and together who respond to the earth quake and destruction of their village by building a mosque. (664) The only other force present is the specter of communism: the 80 military officers executed for being communist, the apparent international communist uprising that is not, the government propaganda against communism. (667) But the mounting uprising remains “the street, the merchants of the bazaar, employees and the unemployed” all “under the sign of Islam.” (667, emphasis added)

This central opposition—the American Shah versus an Islamic popular movement—motivates Foucault’s interpretation of the events in Iran. And it is precisely the Islamic movement that he believes alone could overtake the army: “of the two keys that might control the army, the one that seems more adapted for the moment is not the one, American, of the Shah. It is the one, Islamic, of the popular movement.” (669)

These themes run through the essays. The theme of Islam as the only possible form of opposition in a Cold War context where communism in Iran has been crushed by American domination in the face of the Soviet specter. It is within that geopolitics that Foucault identifies and develops a theory of political spirituality. A thesis about the Iranian uprising as a religious political form, modeled on religious eschatology:

Their hunger, their humiliations, their hatred of the regime and their willingness to overthrow it, they inscribed it all within the bounds of heaven and earth, in an envisioned history that was religious just as much as it was political. […] Years of censorship and persecution, a political class kept under tutelage, parties outlawed, revolutionary groups decimated: where else but in religion could support be found for the disarray, then the rebellion, of a population traumatized by “development,” “reform,” “urbanization,” and all the other failures of the regime? (Useless to Revolt?)

The resulting modality of revolt that Foucault identified and developed in the Iranian context of 1978-79 was framed by the relation between political uprising and religious eschatology. (Sassine interview, 2) And it was, for Foucault, an important discovery—not just in its descriptive accuracy, but also in its normative potential. For, as Daniele Lorenzini correctly emphasizes, “This was what Foucault was looking for: a mass uprising, in which people stand up against a whole system of power, but which isn’t inscribed in a ‘traditional’ (Western) revolutionary framework.”

Foucault did not condemn this mode of political spirituality—to the contrary, he wrote about it with respect and admiration for those who rose up and risked their lives against their oppressors. Foucault did warn that “Islam—which is not simply a religion, but a mode of life, a belonging to a history and to a civilization—risks constituting a gigantic powder keg, at the scale of hundreds of millions of people. Since yesterday, any Muslim state can be revolutionized from within, from the basis of its secular traditions.” (A Powder Keg Called Islam, D&E3 #261, 761). But he traveled to Iran without hostility, rather with sympathy for the uprising. (Sassine interview, 8)

For that, Foucault was excoriated by the French press and by his peers. To this day, Foucault is criticized vehemently for not having taken a position against the Islamic uprising. The book by Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson takes that position, guided by the opening question “Why, in his writings on the Iranian Revolution, did he give his exclusive support to its Islamist wing?” and by its argument that Foucault’s choice reveals deeper problems about his Nietzschean-Heideggerian influence. The controversy continues to the present, with the most recent publication, in 2016, by our guest, Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, of Foucault in Iran: Islamic Revolution after the Enlightenment (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), offering a dramatically opposite reading. On this recent controversy, I will here leave the last word to Talal Asad:

One may recall here a remark Foucault once made in relation to the Iranian revolution: “Concerning the expression ‘Islamic government,’ why cast immediate suspicion on the adjective ‘Islamic’? The word ‘government’ suffices, in itself, to awaken vigilance.” Naive critics of Foucault have taken his interest in the Islamic Republic of Iran as evidence of his romance with political Islam (in response perhaps to his early criticism of the left-wing romance with revolution). But they are mistaken. Foucault’s reaction to the Iranian revolution is his concern (as so often in his writings) to think beyond clichés and, in particular, to formulate questions about how truth is manifested in connection with the exercise of self on self, “the relations between the truth and what we call spirituality”—atopic that preoccupied him in his last years. In the comment about the Iranian revolution he is posing a question about the modern state’s practice of sovereignty and the sovereign subject in that state. The modern state (including varieties of the liberal state) is held together not by moral ideals and social contracts but by technologies of power, by instrumental knowledge, and also, importantly, by the way it requires dependence on and demonstration of truth (traitors are those who conceal the truth).[1]

~~~

At the time, in 1979, Foucault responded to his critics. In both an essay in Le Monde, “Is it useless to revolt?” published on May 11-12, 1979, and in several interviews at the time, Foucault argued that one cannot judge others when they revolt against their oppression and that one cannot judge another who revolts by the outcomes of the ensuing political developments. One should not engage in critical thought about political practice from a position of hindsight. (I believe that the Arab Spring now lends additional support to this position).

In perhaps his most direct response, drawing on his histories of the asylum and of the prison, Foucault wrote:

One does not dictate to those who risk their lives facing a power. Is one right to revolt, or not? Let us leave the question open. People do revolt; that is a fact. And that is how subjectivity (not that of great men, but that of anyone) is brought into history, breathing life into it. A convict risks his life to protest unjust punishments; a madman can no longer bear being confined and humiliated; a people refuses the regime that oppresses it. That doesn’t make the first innocent, doesn’t cure the second, and doesn’t ensure for the third the tomorrow it was promised. (Useless to Revolt?)

In this sense, political spirituality becomes part of the “counter-conduct” that Foucault explored and developed—and that Arnold Davidson discusses so well in his essay “In praise of counter-conduct”: “After rejecting the notions of ‘revolt’, ‘disobedience’, ‘insubordination’, ‘dissidence’ and ‘misconduct’, for reasons ranging from their being notions that are either too strong, too weak, too localized, too passive, or too substance-like, Foucault proposes the expression ‘counter-conduct.’”[2]

It is here, in his last writing on Iran, that Foucault most clearly articulated what he called his own “theoretical ethic”: “It is ‘antistrategic’: to be respectful when a singularity revolts, intransigent as soon as power violates the universal.” (Useless to Revolt?)

Respectful of the individual who rises up, in order to keep one’s indignation and intransigence for the power that represses. What a remarkable statement—and an excellent place to start our seminar on Foucault on Iran: Revolt as Political Spirituality.

Welcome to Uprising 6/13!

Notes

[1] Talal Asad, “Thinking About Tradition, Religion, and Politics in Egypt Today,” Critical Inquiry 42 (Autumn 2015), p. 206.

[2] Arnold Davidson, “In praise of counter-conduct,” History of the Human Sciences, 24(4):25-41 (2011), at p. 28. As Davidson argues, this relates closely to the “critical attitude,” which he defines as “a political and moral attitude, a manner of thinking, that is a critique of the way in which our conduct is governed, a ‘partner and adversary’ of the arts of governing (Foucault, 1990: 38).” Ibid., p. 37.