By Che Gossett

Black AIDS activism confronts premature death—not as a new violence on the political scene but rather as constitutive violence of modernity, a plantation modernity realized and actualized through the slave ship and the apparatuses of the slave fort as colonial, bio and necropolitical and carceral technologies. HIV is a symptom of anti-blackness and coloniality, as its etiology shows. The epidemiological and zoonotic history of HIV is bound up with anti-blackness and colonialism, HIV is entangled with the “scramble for Africa.” This colonial, eco-cidal and anti-black enterprise was, as Adam Hochschild observes in his book King Leopold’s Ghost (Houghton Mifflin, 1998)—which is indebted to and prefigured by the brilliant work of Walter Rodney’s 1972 text How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and W.E.B. Du Bois’s post WWII text, The World and Africa (Oxford University Press, 1947) —the “largest single land grab in history.”[2]

In their recently published text Atmospheres of Violence (Duke University Press, 2021), Eric A. Stanley contextualizes HIV/AIDS as part of the historical crisis and continuum of coloniality and anti-blackness. “HIV is now generally understood to have first multiplied in pre-independence Kinshasa (then Léopoldville) in the Congo, perhaps moving there from Cameroon, where simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) jumped to humans, creating a new zoonotic disease (HIV).”[3] This follows studies by historians and professors of medicine on HIV—such as Paul M. Sharp, Beatrice H. Hahn and Jacques Pepin—tracing to the colonial period in the Belgian Congo and the genocide of African indigenous peoples under King Leopold’s fascist regime.

After the death of Black queer liberationist Kuwasi Balagoon in 1986 from HIV/AIDS related illness, David Gilbert and other former members of the Weather Underground such as Kathy Boudin and Judy Clark orchestrated peer to peer education HIV/AIDS education programs inside. The ACE program at Bedford Hills formed in December of 1987, soon after a study conducted by the Department of Corrections disclosed the AIDS and serophobic violence faced by incarcerated PWAs in New York.[4] Incarcerated PWAs in the early 1980s faced violence and malign neglect from prison staff, as well as segregation and isolation, as well as alienation and exile from non-HIV positive incarcerated people—the AIDS phobic responses of the outside folded in.

Isn’t it possible that I was attacked by the guards, and not the other way around?

And just how many “weapons of choice” does a shackled person have, anyway?

– Gregory Smith[5]

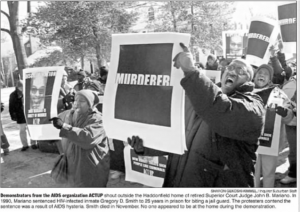

In 1990, AIDS activists including Judy Greenspan of California Prison Focus, ACT UP Philadelphia members including Kiyoshi Kuromiya, and the ACLU organized in support of Gregory Smith, a HIV positive Black gay activist locked up in Camden, New Jersey, who was sentenced to 25 years under HIV criminalization statutes. The assistant prosecutor Harold Kasselman described Smith as wielding his HIV status as “his own personal weapon of misery,”[6] anti-black and anti-queer rhetoric which conjures longstanding imagery of blackness and queerness as lethal threats to the functioning and reproduction of civil society. Even though it was medically proven that HIV was not transmissible through saliva and despite Smith’s testimony that the guard, while beating him and shouting racist slurs, had cut his wrist on Smith’s handcuffs, Smith was convicted and sentenced by Judge Mariano to the maximum of 25 years. William Kunstler represented Smith in an appeal and AIDS activists and the ACLU filed an amicus brief on his behalf. “An appeals court today upheld the attempted murder conviction of an H.I.V.-infected prisoner who bit a prison guard. The court said it did not matter whether the virus that causes AIDS can actually be transmitted by biting as long as the prisoner believed it could.”[7] Smith died while still in state custody at Northern State Prison in Newark, New Jersey, on November 10, 2003. Such loss and suffering, racial and sexual violence is both ritualized and naturalized through the daily operation of the prison industrial complex.

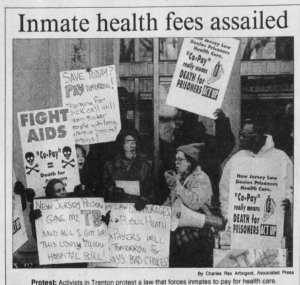

“Greg called us daily with updates on what was happening inside,” said ACT UP/Philadelphia’s Asia Russell. “He reported on the inmates’ concerns over being able to pay to see doctors.”[8] In addition to “diesel therapy”—being moved around from prison to prison to disrupt and destabilize one’s coordinates and community—incarcerated AIDS activists also face political repression and counterinsurgency measures while captive inside, through “ad seg,” or administrative segregation. “Greg believes he is in Ad Seg for trying to organize a prisoner work stoppage against new cost-cutting policies that limit visits and phone calls, eliminate food packages and require inmates to wear only prison uniforms.”[9]

Smith also regularly contributed to the Critical Path newsletter and advocated for AIDS education and treatment inside. Smith fought against the privatization of “healthcare” in New Jersey’s prisons, as he and many others were impacted by the neoliberal shift to single payer care and charged that the company contracted to provide services was errant, which meant that HIV/AIDS medications didn’t arrive on time and that made incarcerated PWA health at risk.

Gregory Smith was murdered by the state but held in collective memory by ACT UP Philadelphia members, his friends and lovers inside and outside and his family. In an act of radical performance designed to both keep Gregory Smith’s memory alive and draw attention to the continued need for better medical care for incarcerated people in New Jersey’s prisons, ACT UP Philadelphia members traveled on buses in January of 2004 to retired Superior Court Judge John Mariano’s home, held a funeral procession, and placed a coffin and flowers on his front yard, making his death visible—a reckoning.

I first found out about Smith when working through Kiyoshi Kuromiya’s archive and seeing their correspondence and Smith’s writing in the Critical Path newsletter over a decade ago.[11] I’m currently completing a political biography of Kiyoshi Kuromiya. On one level biography is also a certain philosophical anthropology. The act of writing a biography can feel like a philosophical experiment of sorts—the problem confronted is how to think through and with—even for—other minds. Yet instead of the sci-fi thought experiment of the brain in a vat (Daniel Dennett) or the phenomenology of what it’s like to be a bat (Thomas Nagel), biographical writing approaches this philosophical quandary with affective possibility (hope and imagination) versus melancholy of the impasse and un-resolvability of paradox (resignation and defeat). Biography creates a historically informed but fictive and imaginative character[12] out of the historical remains of an archive. Perhaps every biography then might be seen as a work of creative non-fiction. The process of writing a biography also reveals the limits of the individuated category of life itself—because (a) life, though singular, is not monadic but rather, shared. Kuromiya’s biography is also the biography of so many others who were part of the movements he was embedded in and passed through.

Perhaps this is one way of interpreting Sylvia Rivera’s resounding call: “We have to show the world that we are numerous. There are many of us out there.”[13]

Kuromiya was an inheritor of abolition. Abolition coursed and flowed through the very Black radical tradition (in the sense of transmission) that he organized in solidarity with, it preceded and exceeded the boundaries of his life and narrative. Born in Heart Mountain Wyoming in an internment camp during World War II, Kuromiya grew up in a securitized and militarized setting of the camp where his family was held for three years. I situate Kiyoshi Kuromiya within a political genealogy of resistance—including abolition—that run a through line connecting the varied movements he participated in. Abolition and the Black radical tradition as political inheritances. After internment Kiyoshi Kuromiya’s uncle, Yosh Kuromiya, was not released, but rather, his incarceration was extended to a federal penitentiary on McNeill Island in Washington State for his refusal to disavow allegiance to Japan and his involvement in organizing at Heart Mountain camp. Yosh’s refusal was not an act of cultural nationalism, instead it rejected the very imposition and problematic of a cruel paradox serving as justification for incarceration. This rejected and refused question was an example of what Lyotard termed the differend[14]—as he could neither express nor forgo allegiance to a sovereign country to which he had no relation as a political subject.

Upon release Kuromiya’s immediate family moved to Monrovia, California—a suburban town. A precocious Kuromiya discerned he was queer while reading the Kinsey Reports at his local public library. Also as a child, he was arrested several times for cruising in the park there and placed in a psych institution as queerness was pathologized and medicalized. Kuromiya ran off to Philadelphia, where he attended the University of Pennsylvania as an undergrad majoring in architecture. Kuromiya participated in the sit-ins with the Congress for Racial Equality in 1962 in Maryland and while leading a group of high school students in Martin Luther King Jr.’s march from Selma to Montgomery he was severely attacked by armed police and hospitalized. Photographs of the bloody scene as well as Kuromiya marching with King, Reverend Shuttlesworth and others by civil rights photographer Jack Rabin are held at the Pennsylvania State archives. In the 1960s and 1970s Kuromiya was part of the homophile movement—participating in the Philadelphia Annual Reminders in 1965 (with Randy Wicker and others) and onward—and following that period, the radical queer movement. He was one of the authors of the “third world gay liberationist” manifestos that emerged out of the People’s Revolutionary Convention convened by the Black Panthers in 1970 at Temple University, which included a demand for sex changes and hormones for all trans people who wanted them.[15] Kuromiya helped to start the Philadelphia Gay Liberation Front and during this entire period was surveilled under COINTELPRO and placed on the national security index. I ordered his FBI file which was over 150 pages and he was regularly monitored by local, state and federal policing agencies starting in the early 1960s with his involvement in SDS.

In 1977 while hospitalized with metastatic cancer, Kuromiya encountered the work of Buckminster Fuller. This began a collaboration that lasted the rest of Fuller’s life and a critical intimacy that extended beyond Fuller’s death, through the posthumous editing, care and publication of his work, as well as his relationship with the extended family. Kuromiya was very close to the Fuller family and helped to transport the coffins of Fuller and his partner Anne from California to Massachusetts after their deaths—which occurred within days of each other—in July of 1983. Having worked with Buckminster Fuller since 1977—serving as his confidant and editor for Critical Path (1981) and the posthumous text published in 1992, Cosmography (Macmillan, 1992)—Kuromiya began the institute that continues to be at the core and heart of his legacy, the Critical Path AIDS Project. Rather than merely recycle Fuller’s grand technocratic and utopian visions of planetary scale, Kuromiya democratized Fuller’s ideas through a scientific and technological praxis rooted in AIDS activism. Kuromiya put the early internet to use for PWA’s (people living with HIV/AIDS), including incarcerated PWAs in Pennsylvania and was co-author of the first standards of care for HIV/AIDS. Kuromiya’s use of the internet, made free and universally available via the Critical Path AIDS project, the project’s newsletter and the bulletin board enabled lifesaving health information to be circulated not through the slow temporality of academic journals or medical and institutional bureaucracy, but rather according to the urgent and pressing needs of patients and activists struggling against premature death from HIV/AIDS. Kuromiya’s politics of care also extended to the everyday—as he provided hospice care for those dying with AIDS and a community chest for HIV/AIDS patients to have access to drugs at no cost and ran a twenty-four-hour HIV/AIDS hotline.

In 1991 ACT UP Philadelphia members established Prevention Point, a needle exchange and harm reduction service provider. At the time, needle exchange was criminalized in the city and Prevention Point started as a DIY and underground distribution network through ACT UP members. It was also a form of political education. AIDS activists foresaw how the so called “war on drugs” was also a war against people living with HIV/AIDS. The so-called war on drugs remains the domestic prosecution of anti-black and racial capitalist warfare. At the same time as providing the services in the wake of what Ruth Wilson Gilmore so incisively terms “organized abandonment”[16] and criminalization—they didn’t wait for them to be legalized and organized to distribute clean needles to drug users—they also pursued the legal and lobbying route. In 1992, after AIDS activists and drug users pressured and lobbied then Mayor Rendell, he made a unilateral decision to issue an executive order, legalizing possession of needles in Philadelphia—even as they were still illegal in the state of Pennsylvania—and still are.

“survival is not only what remains but the most intense life possible” – Jacques Derrida[17]

The etymology of survival means to live on, both in the sense of inheritance but also in the sense of living on after others have died. Thus, survival is often accompanied by feelings of guilt, despair, anguish and outrage. It begs existential questions of fate and chance and luck, the odds, a random calculus. Survival figures as a melancholy form of life. Yet the Freudian distinction, as seen through the writing of Jose Munoz in Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (University of Minnesota Press, 1999) and Dagwami Woubshet in The calendar of loss: race, sexuality, and mourning in the early era of AIDS (John Hopkins University Press, 2015), questions the efficacy of a sharp distinction between melancholy and mourning. The closure of mourning is structurally impossible given the continuity of anti-blackness, and so this presents an avenue for melancholy – and the entirety of what Frank Wilderson terms the “grammar of suffering”[18] – to be re-thought and re-worked. The ‘mourning and militancy’[19] that Douglass Crimp so beautifully wrote of can still be found reverberating and resonating both in the archive and in revolutionary action.

Notes

[1] Image from Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2nd, 2004.

[2] Mary-Lea Cox, “Author Hochschild Recounts Lost History of Horror in the Belgian Congo,” The Wilson Center https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/author-hochschild-recounts-lost-history-horror-the-belgian-congo#:~:text=The%20European%20scramble%20for%20Africa,in%20in%20the%20Belgian%20Congo.

[3] Eric A. Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 52.

[4] Judy Clark and Kathy Boudin, “Community of women organize themselves to cope with the AIDS crisis: A case study from Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.” Social Justice 17, no. 2 (40 (1990): 90-109.

[5] Gregory Smith. “Tales From behind the Wall.” Critical Path AIDS Project Newsletter, Summer. 1997, https://web.archive.org/web/20021224223521/https://www.critpath.org/actup/Project%202.htm

[6] Cindy Patton, “Concealed Weapon,” POZ Magazine, November 1st, 1998. https://www.poz.com/article/Concealed-Weapon-1657-8008

[7] Joseph F. Sullivan, “Inmate With H.I.V. Who Bit Guard Loses Appeal,” The New York Times Feb. 18, 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/02/18/nyregion/inmate-with-hiv-who-bit-guard-loses-appeal.html

[8] Cindy Patton, “Concealed Weapon,” POZ Magazine, November 1st, 1998. https://www.poz.com/article/Concealed-Weapon-1657-8008

[9] Patton, Ibid.

[10] Image from Courier-Post (Camden-New Jersey), March 1st, 1996

[11] For wonderful recent writing on Gregory Smith, see Dan Royles “Tales from behind the Wall: ACT UP/Philadelphia and HIV in Prisons” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (October, 2019)

[12] Thanks to my brilliant partner Anna So for this insight about fiction and biography and the biographical subject as a character.

[13] Wilchins, Riki, et al. GenderQueer-voices from beyond the sexual binary (Riverdale Avenue Books LLC, 2020), 87.

[14] Jean-François Lyotard, The Differend (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1983)

[15] Thanks to Hil Malatino, author of Trans Care (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2020) for reminding us all of this on Twitter.

[16] Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California (Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Press, 2007), 178

[17] Jacques Derrida, Learning to live finally: The last interview (Melville House: 2011, 52).

[18] See Frank Wilderson III, Red, white & black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

[19] Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and militancy.” October 51 (1989): 3-18.