To talk about independence, insurrection, autonomy, I’ll use three photographs as my point of departure—two of Fortino Sámano, about to be executed on March 2nd, 1917, and one of Pablo López, also about to die on June 5th, 1916. The fate of the two men is similar in many ways. Both participated in the Mexican Revolution, both were very young (neither was 30-years old), and the two of them face imminent death in a casual, nonchalant, even defiant way. Perhaps their boldness should not be surprising. As men participating in the armed struggle, they could have been killed many other times. López, in fact, had recently survived an attack—the crutch he holds under his left arm is a reminder of the injuries he had sustained, of how he had been hiding and incapable of moving, a few weeks before.

That is, to the extent that these men were willing to die—and they were, otherwise they would not have been fighting—their pictures, their death by firing squad, add nothing to a story of risks taken and assumed, that had been foretold. And yet, the photographs also remind us that it’s one thing to die in the midst of the battle, but another thing to know they are about to be shot by a firing squad, that they have a few minutes, seconds? to choose a particular stance, a final bearing that could condense all they stood for and were. Sámano and López are not dying in battle, instead they had time to think, to take in the fact that there was someone there with a camera, ready to capture a permanent impression of their last attitude toward death, toward life. What would, could, they communicate? But then again one has to wonder if they really had the time. Or is it precisely in those very last minutes that they lost all possibility of preparing a stance, and instead something deeper, more truthful than a prepared script, emerged? Or perhaps a combination of both?

Agustín Casasola’s images of Sámano do not show a submissive, repentant man (he had been accused of robbery), but on the contrary someone who faces what’s to come with eyes wide open, so to speak. But there’s more than this. In the first photograph, Sámano shows us the pressure of the moment (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Agustín Casasola, Fortino Sámano, de pie frente a un paredón para ser fusilado, retrato. ARCHIVO CASASOLA.

The elegance of his clothes, knee slightly bent as if resting, hands in his pockets, might make it seems as if he were making a brief stop during a stroll in the park, but all of this is betrayed by the dirt on his shirt, his untrusting eyes, his tightly clenched cigar. The tension is high in this very alone figure. In the second photograph a resolution was reached, no more ambivalence: a firmly held hat showing respect, and a straightened body posture with his face looking forward expresses no doubt (Figure 2). The shirt, tucked in rapidly as if its owner had been caught unprepared in the first photograph, has been covered by his coat in the second, as if a split second before the shot was taken he had said to himself, here we go, and then arrange the coat, the hat, and go. A form of regaining control when apparently there was none.

Fig. 2. Agustín Casasola, El Capitán Fortino Sámano en espera de ser fusilado. ARCHIVO CASASOLA.

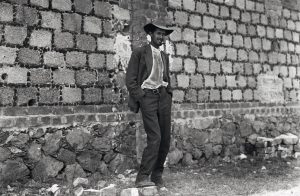

For his part, Pablo López, his whole body against the wall, a wall that bears the markings of many other executions, is in a different state (Figure 3). Were it not for the accounts of this very moment, perhaps we would not know that he’s probably uncomfortable, in pain: his bent knee, his looking for the support of the wall, his slender body, have to do with the bullets he had taken, the blood he had lost, the hunger he endured. Nevertheless, like Sámano, and maybe more so than him, he seems ready. Looking directly at the camera, indifferent to the people on his right, as if the line dividing the wall separated him from them as well. Worlds removed from one of the soldiers who are about to kill him, he looks on. López holds himself with a hint of ironic knowledge, and with more self-respect, than the high ranking officer who seems out of place, like an extra unsure of his role. The photograph is about López.

Fig. 3. Anonymous. Pablo López

As recordings of convulsed times, the photographs might erase the difference between the two moments, the two men. They might appear to materialize the often-cited Mexican indifference toward death, a supposed national closeness to it. Viewed in this sense they are disturbing because they erase the politics behind the Revolution, or any other struggle. They show two of many young men about to be killed, as if the Revolution (and many thought this exactly) were an unsalvageable waste of life whose very excess—and the one million lives it took is indeed extremely high—extinguished all other meanings. Young people died and that’s what we see. Even in cases in which the viewer, the readers know the reasons for the struggle, the undeniable violence of the moment (of any insurrection, perhaps) along with the negative results of the Revolution in this case (and what for?), give some people (many of my students, for example) a reason to pause. They provide a cautionary tale about the futility, again, the waste, of insurrections which lose their reason for being along the way.

I take then these photographs as a way to enter into a discussion on the relationships among death and insurrection (I am aware of this group’s previous conversations differentiating between insurrection and revolution, but allow me to use the words in this way), politics and life, not because it is necessary (there are many ways to approach this issue: tactics, strategy, overarching political programs, etc.), but as a way to clarify my own thinking in order to provide a better response to my skeptical students, but also to understand what is at stake in armed insurrections in general, and the Mexican Revolution in particular.

To do that the context of the photographs is important. And it matters that Sámano, a Carrancista, spent his last days arguing his innocence in the crime for which he was about to get killed by his own army. He was angry, we’re told by the newspapers of the period, but proud because he knew who he was. Yet, in 1917 he was a colonel in Carranza’s army, which means he had been fighting against Villistas and Zapatistas, that is, he was part of the faction that in the name of order had betrayed the Revolution, and reduced it to timid reforms. Whereas López, the young general, was a Villista, who, injured as he was, refused to surrender to or apologize for having participated in the attack on Columbus, New Mexico, and whose last two wishes were first to request that the one U.S. person among the “public” attending his shooting be removed, and second to ask that the shots be directed at his chest. Ruthless as the Villistas supposedly were, López’s group had decided not to stop in spite of the many losses—and in 1917 the Villistas knew about this—and to press on because they were sure of what they wanted and deserved.

The photographs show single men, and not the communities, the ideas, the realities for which they fought. That is, they show us men about to die, but not the lives that sustained the actions that lead them there. In this way, they can conceal the politics of the strong affirmation, the “here I stand,” crutches and all, of López. But to talk about independence, insurrection, and autonomy it is necessary to remember that these photographs are not therefore, an acceptance of the unacceptable, death, but quite the contrary, in the contrast between them they should be seen to represent more than sameness in death, a profound disagreement on life and politics.