By Jack Halberstam

This semester I have been teaching a class titled “World’s End.” In the class, we are reading both post-apocalyptic literature, standard zombie fare, as well as more speculative works that imagine how worlds end and how other worlds emerge. The category of ‘world’ is itself under scrutiny here, and “end,” as in “end of the world’ is itself a rather loose temporal marker. But the idea of “world’s end,” like the concept of “Becoming Numerous” is designed to break with the continuity of history, the forward momentum of progress and the endless focus on individual survival. Many of the novels and films on my syllabus actively imagine the collapse of the world crafted by global capitalism, and a few offer alternatives to it. The power of the speculative work I have assembled under the heading of “world’s end” however is not that it serves as an archive for world-building according to a feminist or queer agenda, but instead, most of it advocates very forcefully and specifically for world-breaking, world-unbuilding and for a dismantling of life as we know it.

While an earlier moment in queer studies made its investments firmly into the utopian project of world-making, I am thinking about how to unmake this world, and how to continue the work begun by an earlier generation of activists who wanted to smash dominant systems (smash patriarchy!) and bring oppression structures down. For example, in the 1970’s there were many feminist expressions of violent refusal (Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto, Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames, the Dutch film A Question of Silence about the spontaneous murder of a man by three anonymous women); there were also stunning examples of aesthetic practices committed to collapse (Alvin Baltrop and Beverly Buchanan) and activist projects that sought to refuse political inclusion altogether (Combahee River Collective). These earlier projects that sought to unmake and unbuild structures are much more meaningful to me, and seem much more resonant for current activist movements, than over-memorialized events like Stonewall. As Martin Manalansan, among others, has proposed, what we call “Stonewall” is a false and imperial memory of a singular event that supposedly shifted public attitudes about queerness from incomprehension to understanding and initiated social change. In reality, the Stonewall rebellion was a small event within a much larger arc of struggle and, as Leslie Feinberg’s incredible novel, Stone Butch Blues, makes clear, queer bars were raided by the police long before Stonewall and long after, and on multiple occasions, butches, queens and queers fought back, got arrested, went to jail and faced public rituals of shaming and punishment. Stone Butch Blues also documents and narrates collaborations between queer and transgender activists and working-class unions who all worked together to use strikes and walk-outs to oppose dangerous working conditions and gender-based violence and homophobia. The Stonewall rebellion appears in Stone Butch Blues as an event that, when they hear about it, compels the butches, the femmes, the hookers and the queens to resolve not to submit any more to police harassment, but the Stonewall rebellion itself, for most people outside the New York metropolitan area, was news from afar that may or may not have impacted local configurations of violence, social disapproval, queer life and trans vulnerability.

The narratives circulated about the drama of Stonewall change as each era reimagines the event for itself. At first, the story of the Stonewall was focused upon white gay men – indeed, the plot of the hapless film Stonewall, from 2015 directed by Roland Emmerich, literally turned the whole thing into the coming out story of a young white gay man from a small town in Indiana who arrives in the big city and falls in with a multiracial group of street kids and queens. He then somehow ends up leading the charge against the police when they come to raid the Stonewall Inn. This representation has been hotly contested through oral histories and more recently Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera have been named as the instigators of the action at the bar. Regardless of this shift from gay white men to trans women of color as leaders of the rebellion, the framing of this moment as revolutionary is part of the mainstreaming of queer culture and it condenses an array of complex aesthetic and political expressions into a series of individual acts and statements that can be readily digested within the socially accepted framework of political change and within a conventional rendering of revolutionary action.

And this is not to say that Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were not extraordinary figures, marginalized, brave and fierce, precarious and imaginative. They were all of that and more but they cannot be used to stand in for all the political activists who have not survived in the historical records. Just to give an example of a forgotten queer figure who challenged trans-exclusionary feminism, played music in bars and at festivals and was arrested for singing a song about being queer in public in 1969, I offer: Maxine Feldman. Feldman was a kind of unusual women’s music musician – she identified as a “big, loud, Jewish butch lesbian” and in later years, according to her partner, identified as transgender! Max(ine) Feldman came out as queer early in life and was expelled from school for doing so and a doctor proposed electro shock treatments for her, which she refused. Feldman was queer before queer, punk before punk, and angry long before Stonewall. Indeed, her most powerful anthem is a song titled “Angry Atthis,” written and performed in the late 1960s and credited as one of the first out lesbian songs to be performed publicly. Indeed, the police showed up at a concert at Ventura College by Feldman in 1969 and the concert was shut down after this song was played and Feldman was charged with public indecency for singing a song about being queer. In this song, Feldman, a butch singer with a very low and full voice, veers away from the soft and soothing rhythms of so-called Women’s Music and pioneers a kind of early lesbian punk music: https://youtu.be/-ZwnYY2Yg78

Angry Atthis is an astonishing song that builds in intensity, claims words like “queer” and “lesbian” and turns folk into punk, punk into lesbian rage and “women’s music into trans rebellion.” At times in the song, her deep voice growls lyrics like “feel like we are animals in cages” – the next line uses enjambment – “and have you seen the lights in the gay bars” to remind us that gay bars were not simply places of freedom but also sites of quarantine, secrecy, furtive and shameful activity and they had a carceral feel. The song sums up the mood of the pre-liberation reality of queer lives. The fact that this singer with their low voice, their tuxedo and their acoustic low-fi performance has been totally forgotten now, despite their arrest in the months before Stonewall, reminds us of how lesbian/trans masculine history as a category has been cordoned off from protest altogether and obliterated by the charisma exerted by Stonewall. And the goal here is not to just add more names to the wall of memory, but instead we should think of other methods of archival retrieval, memorialization and precedent that contribute more meaningfully to the goal of becoming numerous. So, let me offer two examples of abstract queer rebellion for discussion, examples that are not available within the arc of rebellion that stretches from Stonewall to ACT UP to gay marriage but that offer different lexicons for revolution, rebellion and change.

1. Alvin Baltrop: The Aesthetic of Collapse

While the police were raiding Stonewall and harassing queers, a whole other scene of queer and trans life in the 1960’s and 1970’s was unfolding on the west side of the city where the Hudson River piers had fallen into disrepair. In the wake of de-industrialization and the collapse of the shipping industry, the piers, massive empty hangars filled with debris and beginning to collapse, became home to a vast sexual and social ecology of queer life. Gay men cruised here, homeless kids slept here, drug addicts scored and sold drugs here. It was a dangerous space but also a place where the police never patrolled and art, sex, and cruising remade the abandoned spaces into landscapes of everyday rebellion. Sylvia Rivera and Masha P. Johnson among many others lived at the piers at various times and David Wojnarowicz made murals on the crumbling walls.

My interest in the piers skirts the scenes of sexual experimentation that have been documented so vividly by Samuel Delaney and others. I am drawn instead to the collapsing architecture that became a frame and symbol for a different kind of rebellion, that marked an alternative set of relations between space and bodies, and that left behind an aesthetics that merged eroticism with unstable structures. Alvin Baltrop, a former marine and an African American photographer spent a decade or so in the 1970’s and 1980’s taking stunning photographs of gay men cruising in these spaces of destitution. His photographs were quite unique and developed a visual language that emphasized the uniqueness of the space and the drama of the collapsing buildings. His photographs were often taken from a distance and the viewer would have to work to see the scene of sexual encounter which would be dwarfed by the timbers, fallen girders, crumbling masonry and massive windows with no glass, open to the sky and the river. His photographs seemed to say – human life is small, inconsequential, the world is falling down, welcome to the revolution. Unbuild everything. Revel in collapse.

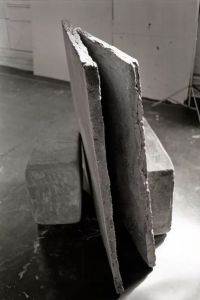

2. The Semiotics of Demolition: Beverly Buchanan

Buchanan, a Black lesbian (she did not use this term but her primary relations were with other women) artist who had grown up in North Carolina, was in NYC in the 1970’s, just after Stonewall and around the same time that Alvin Baltrop was taking photographs at the piers. She was in NYC to attend Columbia for an MA in public health. While in the city, she started taking painting classes and met Norman Lewis and through him she was introduced to abstract art and minimalist painting and was deeply influenced by Romare Bearden. Soon, Buchanan decided to drop out of medical school and become an artist full time. Her first show in 1972 consisted of drawings of Black walls with mottled surfaces, the walls were undefined and in a state of decay. Of these early works which she called “City Ruins,” she said:

My interest in walls involves the concept of urban walls when they are in various stages of decay; walls as part of a landscape. Often, when buildings are in a state of demolition—one or two structural pieces (Frustula) stand out that otherwise, never would have been “created.” This state of demolition presents a new type of “artificial” structural system piece that by itself (its undemolished state) would not exist. These “discards” or piles of rubble can be pulled together to form new systems. These new systems are very personal statements to me. They are inspired by urban ruins but are created, “in my own image” by me, in concrete and painted with dark paint. Deceptively, they appear to be black. (One of my dreams: to place fragments in tall grass where a house once stood but where, now, only the chimney bricks remain.) (Buchanan, n.d.).

This is an extraordinary statement and one that speaks directly to the potentiality that lies coiled in scenes of collapse, in the fragmentation and the new politics forms that emerge. When something comes apart, Buchanan proposes, we are confronted with a new sign system, with different points of support, new entry ways and exits, the rubble and rejected matter become the foundation for something else, something that could not be created but must just show itself –like the unions between metal and flesh in Alvin Baltrop’s photographs of the piers. Buchanan went on to make land art in Georgia and to build concrete boulders precisely so that she could set them in landscapes where they would decay and disintegrate. Crafting concrete boulders and placing them in marshy areas where they would blend into their surroundings and possibly be absorbed by them, Buchanan clearly wanted her work to reckon with time, ephemerality, fragmentation and incompleteness. In one notebook, she described the boulders as: “Not weak in the sense of an instant falling apart at the seams. Rather – it is made to eventually crumble. How fast or slow it becomes a ‘ruin’ is unknown. How long do modern paintings last?” (1977). “It is made to eventually crumble” – Buchanan designs the boulder to hide from view, to disappear among the marshes and then to crumble – its goal here is not to build a world, the goal is ruination and collapse. What can we learn from these counter-intuitive examples of quiet rebellion? Do we know how to live on after the end of the world?