By Bernard E. Harcourt

I would be sitting in a special locked isolation cell, sometimes even with the lock welded shut, and there would be no one to talk to – just the sound of screaming voices. And because there is no human contact, you depend on books. No contact with people. Special lock welded on the door. Nobody around. I’m strictly by myself. The only friend I had was a book. Sometimes I find myself talking out loud to the author. I’d sort of wake myself up and I’d hear myself talking to this other person. I guess it was like some kind of wish fulfillment. When I’m asleep at night, I still find myself talking to those guys.

— George Jackson[1]

Those authors, George Jackson listed them: the Black Panthers, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Marx, Mao, Lenin, Trotsky—all, worldly, revolutionary philosophers.[2] Albert Woodfox recounted them as well: George Jackson, Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Steve Biko, Eldridge Cleaver, J.A. Rogers—and Mao’s Little Red Book, Ho Chi Minh, and other revolutionary thinkers.[3] Their writings created revolutionary cycles that regenerate critique and praxis in and outside the prison.

Equally remarkable is each individual rotation—each individual journey along the path of politicization, of consciousness, of self-transformation.

In many ways, that is the brilliance of the way in which George Jackson’s prison letters read in Soledad Brother. They carry the reader along Jackson’s personal journey, from his earliest letters addressed to his father, dated June 9, 1965, asking for some books and reading materials by Mao Tse-tung and W.E.B. DuBois,[4] to his request a few months later, September 6, 1965, again to his father, for “a portable typewriter and of course the carrying case.”[5] “Send a lesson book also,” Jackson adds. “A used one will be all right.”[6] And from those early encounters to his political awakening and, ultimately, to the radical revolutionary writings that he penned calling for “a true internationalism with other anti-colonial peoples.”[7]

His letters to Angela Davis in May 1970 chart that personal journey and his quest for critical thought and praxis. “’One doesn’t wait for all conditions to be right to start the revolution, the forces of the revolution itself will make the conditions right,’” he writes to Davis. “Che said something like this. Write me and let me have it straight.”[8] George Jackson’s letters trace a journey of reading, and writing, and thinking critically, going over the words, putting them in action, getting them right. A journey that would lead to the even more revolutionary letters of Blood in My Eye, where Jackson is so directly in conversation with revolutionary figures like Nkrumah—one hears this so clearly in passages like the one where, discussing African societies, he writes “those which allowed capitalism to remain are still neo-colonies”[9]—where he writes so openly about the need for revolutionary change and where he prefigured his own death: “If we accept revolution, we must accept all that it implies,” he wrote: “repression, counter-terrorism, days filled with work, nervous strain, prison, funerals.” (41) That long journey led Jackson to become, in the words of Joy James, a “dragon philosopher and revolutionary abolitionist.” At the seminar, we were honored to walk with Albert Woodfox and Paul Redd and retrace their journeys.

One of the central themes raised by Joy James at Revolution 7/13 concerns the role of critical academics in relation to prison writing, study, and political praxis. James spoke of the need for courage for those in the academy—the courage “to read and not just be a consumer, but be an ally.”[10] James urged those in the academy to actualize that ambition—an ambition that is at the very heart of this seminar.

Paradoxically, the interventions of Albert Woodfox, Paul Redd, and Darryl Robertson convinced me that the most genuine and authentic academy is the one created by the women and men behind bars, in solitary, on the Short Corridor, at Angola or Parchman Prisons, at Rikers. In their reading groups and teach-ins, in their critical examination, study, and debate, and in their resulting political practices, the people behind bars form the true academy.

When a man on death row writes to Albert Woodfox, by way of Woodfox’s attorney George Kendall, that “I myself & some other socio-politically conscious comrades have been having teach-in sessions with your book, Solitary, here on […] Death Row”;

when Albert Woodfox describes how he and Herman Wallace aspired to two hours of reading every day and daily teaching, debating, and discussing the principles of the Black Panthers[11];

when the men on the Short Corridor at Pelican Bay State Prison miraculously find ways to pass torn pages from the books of George Jackson, Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault, Bobby Sands, and others, through the vents and cracks of their solitary cells, and when they manage to debate and critique these writings, envisage new ways to understand their incarceration, and develop new practices to resist[12];

when Darryl Robertson is released from Rikers Island and walks out of the New York County Criminal Courthouse at 100 Center Street in downtown Manhattan carrying, as his only property, as his only possessions, two 75-pound bags of books, more than a hundred books, as the only thing that got him through his time at Rikers;

when Darryl Robertson is released from Rikers Island and walks out of the New York County Criminal Courthouse at 100 Center Street in downtown Manhattan carrying, as his only property, as his only possessions, two 75-pound bags of books, more than a hundred books, as the only thing that got him through his time at Rikers;

then it becomes clear that these spaces built to confine, to punish, to do violence to men and women—the Short Corridor, the Red Hat at Angola, Rikers Island, prison and jail cells—these spaces have been turned into, by the people who are imprisoned there, the true and genuine academy where critical thought and debate is really most alive.

Our venerable halls of higher education, our ivory towers, for the most part, pale in comparison. More often, at our schools, colleges, and universities, there just isn’t the same drive, the same hunger, the same need to read, to critique, to engage in praxis—to confront our situation and pursue genuine and radical self-emancipation and liberation.[13]

Listening to Albert Woodfox, Paul Redd, and Darryl Robertson—especially, for instance, when Albert Woodfox speaks of dialectical materialism so seamlessly and in a way that makes possible genuine public exchange and understanding (without any of the jargon that academics typically use)—it is clear that we are in the company of the true and authentic critical theorists and practitioners.

Moving forward, then, as we formulate our inquiry, it is not what academics can contribute to the critique and praxis of men and women behind bars, but instead, the reverse: How can we in higher education transform ourselves to better model the relation between critique and praxis in the true academy that the people in prison create—while we seek to abolish and tear down the prison itself?

As for whether there exist any models for this in higher education, I am drawn to one at least, one historical episode that I think is worth mentioning—there are others of course.

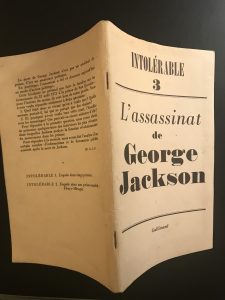

When I came home from Revolution 7/13, I found my copy of the pamphlet that the Prisons Information Group (Groupe d’information sur les prisons or “GIP”) published with Gallimard press in France on November 10, 1971, less than three months after the homicide, under the title “The Assassination of George Jackson.”

With a preface by the writer Jean Genet (who himself had been incarcerated), two translations of interviews with George Jackson, and three essays, including the essay “L’Assassinat camouflé (“The Masked Assassination”) written by Michel Foucault, Catherine von Bülow, and Daniel Defert (which was translated into English and published in a collected volume edited by Joy James[14]), the GIP tract took on the “assassination of George Jackson” just three months after it happened. It offers a militant critical take. On the back cover, it declares:

The death of George Jackson is not just an accident that occurred in prison. It’s a political assassination.[15]

Jean Genet opens the tract, in his preface, with these powerful words:

It is more and more rare in Europe that a person accepts to be killed for the ideas they espouse. Blacks in America do it every day.[16]

Foucault, von Bülow, and Defert continue, in their essay:

Jackson already said it: what is happening in the prisons is war. A war that has other fronts: in the black ghettos, inside the army, before the courts. […] Today, the imprisoned revolutionary militants and the common-law prisoners, who’ve become revolutionaries during their actual detention, have allowed the war front to pass inside the prisons.

Jackson’s assassination will never be judged by the American justice system. No court will really try to find out what happened: It was an act of war. And what has been published by the ruling power, the department of corrections, and the reactionary newspapers must be considered “war communiqués.”[17]

Just three months after the homicide of George Jackson, the GIP had the leading French press, Gallimard, publish a 64-page tract analyzing the shooting and the cover-up, and asking critical questions:

1. Who then was this living person who we wanted to kill? What threat did he present, he who was carrying only chains?

2. And why did we want to kill this death, to suffocate it under lies? What could we still fear from it?[18]

And while Genet, von Bülow, Defert, Foucault, and others were conducting these inquiries, writing these tracts, publishing prison writings, exposing prison conditions, publicizing the words of those inside through the GIP, Foucault was researching and writing a monograph that he would publish under the title Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, and that would eventually be read, debated, critiqued, torn up and passed through the vents and cracks of solitary cells in the Short Corridor thirty-five years later and contribute to the men in the SHU theorizing their torturous condition and planning political action.

Militating with the GIP, publishing pamphlets, while writing a book that contributes to those revolutionary cycles—that may be a model for critical thinkers in higher education. No model is perfect, and it is critical that we now tend to the intellectual blind spots that Joy James rightly identifies[19]. This exemplar from the early 1970s, though, shines some light on the question of critique and praxis for those of us in the university.

A brilliant young visiting scholar left our seminar tonight telling me that what he enjoyed most about it is that it is making critical theory dangerous again. How could it be otherwise? How could it ever remain critical and not be dangerous?

There can be nothing dogmatic about revolutionary theory.

—George Jackson, Blood in My Eye (1971) 13, 14.

Notes

[1] George Jackson, Unpublished Interview, quoted in Blood in My Eye (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1971), xiii-xiv.

[2] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 5; George Jackson, Soledad Brother (1970), 16.

[3] Woodfox, Solitary, 161.

[4] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 61.

[5] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 74.

[6] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 75.

[7] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 264.

[8] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 290.

[9] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 4.

[10] Fonda Shen correctly pointed out after the seminar that we were using the term “academy” in a more narrow sense to speak of the critical academy or the abolitionist academy or, in effect, the part of the academy that embraces critical theory and praxis. It is probably true that the vast majority of the academy more broadly actually contributes to racialized mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex, especially the vast criminal justice programs that feed the police forces and departments of corrections.

[11] Albert Woodfox, Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement (New York: Grove Press, 2019), 95.

[12] Paul Redd presentation at Revolution 7/13; see also Allegra McLeod, “Law, Critique, and the Undercommons,” in Didier Fassin and Bernard E. Harcourt, eds., A Time for Critique (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 256.

[13] I use the terms “emancipation” and “liberation” advisedly here, trying to get at a notion of radical self-transformation. Joy James offers a pointed critique of the term “emancipation” in her work on (Neo)Slave Narratives and Contemporary Prison Writings, associating the use of the term emancipation mostly with the more conservative state discourse on the emancipation of slavery (i.e. the Thirteenth Amendment, which makes possible prison slavery) and the more moderate advocate-abolitionism of persons who are not prisoners. James compares it, unfavorably, to the more positive notion of freedom. “Emancipation is given by the dominant, it being a legal, contractual, and social agreement,” James writes. “Freedom is taken and created” (James, The New Abolitionists, xxii). I agree with James’s critique; but I have reservations about the notion of “freedom” or “liberation” as well, as sometimes suggesting, too optimistically, that we can truly and completely get beyond relations of power. This would deserve a full dissertation. Suffice it to say here that I am trying to reach for a conception that involves genuine radical self-emancipation leading to as much freedom as could humanly exist.

[14] Michel Foucault, “Masked Assassination,” 140-160, in Joy James, ed., Wafare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

[15] Groupe d’information sur les prisons [Prisons Information Group], Intolérable 3. L’assassinat de George Jackson [“Intolerable #3: The Assassination of George Jackson] (Paris: Gallimard, 1971), back cover.

[16] GIP, Intolérable 3, 3.

[17] GIP, Intolérable 3, 41-42.

[18] GIP, Intolérable 3, back cover.

[19] Joy James, Resisting State Violence: Radicalism, Gender, and Race in U.S. Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 29; Joy James, “Violations (for Emily),” 3-16, in Joy James, ed., Wafare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 6, 8-9.