By Romany Webb

Australia has a long, proud tradition of environmentalism. It is home to the second oldest national park in the world (after Yosemite) and was one of the first countries worldwide to adopt species protections. Despite this history, however, Australia has given up its leading position in recent years. This is especially true in the area of climate change, where Australia is at the very back of the pack, consistently ranking as one of the worst performers worldwide.

Australia has a long, proud tradition of environmentalism. It is home to the second oldest national park in the world (after Yosemite) and was one of the first countries worldwide to adopt species protections. Despite this history, however, Australia has given up its leading position in recent years. This is especially true in the area of climate change, where Australia is at the very back of the pack, consistently ranking as one of the worst performers worldwide.

The Australian government has a modest goal of reducing climate-damaging greenhouse gas emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. It has, however, adopted few concrete policies to ensure achievement of that goal. For example, whereas other countries have mandated emissions reductions in electricity generation and other sectors, no such mandates have been adopted in Australia. Nor does Australia have any long-term plan for reducing its use of high-emitting fossil fuels in generation and other applications. That’s long been a concern for local environmentalists. It should also worry anyone with an interest in reliable electricity as, according to a new government-commissioned study (the “Finkel Report”) published on June 9, “[t]he lack of a transparent, credible and enduring emissions reduction mechanism for the electricity sector is now the key threat to system reliability.”

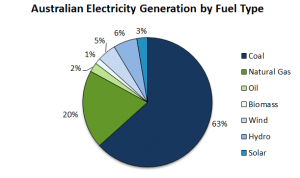

Australia currently obtains approximately two-thirds of its electricity from coal-fired generating units. The continued use of coal has been supported by successive governments, with former Prime Minister (“PM”) Tony Abbott recently declaring that the fossil fuel is “good for humanity” because its development and use supports economic growth, and his successor PM Malcolm Turnbull suggesting that it is needed to ensure “energy security.” At the same time, however, there is growing recognition that continuing to use coal will make achievement of Australia’s emissions reduction goal difficult and perhaps impossible. (It was, for example, recently reported that Australia will need to shut its coal generating units at a rate of one per year until 2035 to meet its emissions reduction goal.)

Recognizing this, and concerned about the potential for future emissions controls, industry participants have been reluctant to invest in new coal generating units. Thus, according to the Finkel Report, “aging [coal] generators are retiring . . . but are not being replaced.” Little has been done to encourage alternative generation, for example using wind and other renewable resources. While the government has adopted a renewable energy target (“RET”), under which electricity retailers are required to purchase credits to support renewable generation, that scheme is extremely limited. Even with the RET scheme, renewable generators are expected to provide just 23.5 percent of electricity by 2020, well below the rates achieved elsewhere. (For example, a similar program in California is expected to result in 33 percent renewable electricity by 2020, rising to 50 percent by 2050.) The Australian government has not indicated whether the RET scheme will be renewed post-2020 or what (if any) other policies will be adopted to support renewable generation. Nor has it provided any guidance on future policies with respect to fossil fuel generation.

According to the Finkel Report, uncertainty about the future of energy and climate policy in Australia has discouraged investment in new generation, threatening electric system reliability. The report concludes that, before generators will make investments needed for reliability, they must have “clarity regarding the future of Australia’s emissions reduction policy.” It therefore calls for the establishment of “a long-term emissions reduction target for the electricity sector [and] a credible and enduring mechanism for the sector to achieve” that target. The report describes two key mechanisms:

- An emissions intensity scheme (“EIS”), which would effectively involve emissions trading. The government would set an emissions baseline for the electricity generating sector. Generators with emissions above the baseline would have to purchase credits from generators with emissions below the baseline.

- A Clean Energy Target (“CET”), which would operate similarly to the current RET, providing incentives for low-emission generation. Generators would receive certificates based on how far their emissions fall below a specified threshold. Retailers would be required to purchase those certificates to demonstrate that a certain share of their electricity comes from low-emission sources.

Adoption of an EIS has been supported by a number of industry and other bodies, including the national Climate Change Authority and Australian Energy Market Commission. Despite this, however, the government last year ruled out adoption of an EIS on the basis that it could lead to higher electricity prices. Contrary to this claim, the Finkel Report indicates that adoption of an EIS would actually result in lower electricity prices between now and 2050, compared to a continuation of the status quo. So too would adoption of a CET. Both mechanisms would deliver significant benefits, reducing emissions while maintaining system reliability. Hopefully this will be enough to convince the government to act and restore Australia to its rightful position as an environmental leader.

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.