By Michael Burger

Climate change nuisance litigation is entering a new and dynamic phase. Tomorrow, Thursday, May 24, Judge William H. Alsup in the federal district court in San Francisco will hear oral argument on motions to dismiss filed in City of Oakland v. BP P.L.C., a consolidated case in which Oakland and San Francisco claim that five fossil fuel companies’ production and promotion of fossil fuels constitutes a public nuisance under federal and California common law. Three weeks later, on June 13, Judge John F. Keenan of the Southern District of New York will hear oral argument on the motions to dismiss filed in City of New York v. BP P.L.C., a case in which New York City alleges these same companies’ same activities constitute a public nuisance and trespass under New York State law. The decisions on these motions could influence pending and future litigation in the same vein – lawsuits seeking damages, compensation or abatement funds to alleviate the costs borne by local governments to adapt to climate change impacts.

At the moment, it’s pretty messy out there. There are eight other climate change tort cases pending: six alleging nuisance and a variety of other state common law violations in California courts, one claiming state public nuisance along with other state common law and statutory violations in Colorado, and one claiming state public nuisance and trespass in Washington. One set of California cases – filed by San Mateo County, Marin County and Imperial City – was removed by defendants to federal court, then remanded to state court, based on Judge Vince C. Chhabria’s conclusion that federal common law has been displaced and that state law should govern the cases – a conclusion opposite to that previously reached by Judge Alsup in a decision preserving the removal of the Oakland/San Francisco case. Judge Chhabria then certified his decision for interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit, and in March defendants filed their petition. Late yesterday, May 22, the Ninth Circuit panel denied the petition for interlocutory appeal. A separate appeal, challenging Judge Chhabria’s decision that the federal officer statute does not require removal, is pending, with briefing scheduled to take place over the summer. Meanwhile, a second set of cases – filed by Santa Cruz County, the City of Santa Cruz, and the City of Richmond – have also been removed to federal court and assigned to Judge Chhabria. A motion for remand has been briefed. The cases filed by the City and County of Boulder, Colorado, and by King County, Washington are still young, and defendants have not yet responded to the complaints.

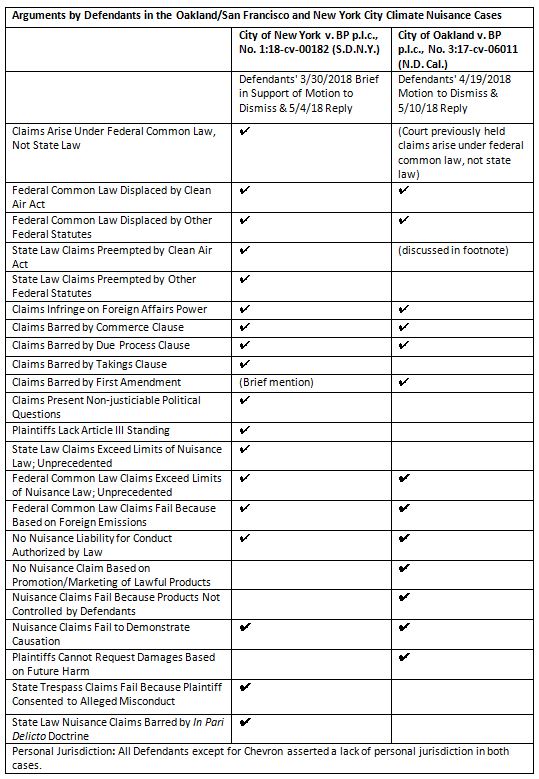

The table below, pulled together by summer intern Patrick Woolsey (Yale Law School/Forestry & Environmental Studies, ’19) seeks to summarize – in a simplified manner – the arguments set forth by the defendants in the Oakland/San Francisco and New York City cases. Plaintiffs’ arguments, broadly construed and without getting into specifics, are that defendants are wrong on each point.

These arguments – about displacement of federal law, preemption of state law, the foreign affairs power, political question, standing, the applicability of common law to defendants’ activities, causation, and so on – will recur in the other lawsuits, when they get to the motion to dismiss phase. Here, I want to just flag two meta-questions that I think are central to these cases, that cut across the particularized legal debates, and that are likely to feature in any and all of the litigation to come:

First: Are courts the appropriate branch of government to determine rights and assign responsibilities for the production of fossil fuels and its consequences? Defendants argue that the other branches have through their actions and by virtue of our constitutional structure occupied the field, so to speak, in this area. For instance, federal legislation establishing national energy policy, providing for the leasing of federal lands, and setting up permit schemes for fossil fuel production activities, according to defendants, displaces federal public nuisance claims and preempts state common law claims. The global nature of the climate change problem and its potential solutions, according to defendants, means both that court intervention would “infringe on the federal foreign affairs power” and that there are no manageable standards for a court to apply to plaintiffs’ claims, making it a necessarily political question. As I’ve noted in an earlier blog looking at preliminary issues in these cases, the Supreme Court found in AEP v. Connecticut that the Clean Air Act displaced a federal nuisance claim seeking to enjoin the direct greenhouse gas emissions from a handful of power companies, and the Ninth Circuit found that that holding controlled a separate suit seeking damages from emissions. But the Second Circuit (in Connecticut v. AEP) and the Fifth Circuit (in Comer v. Murphy Oil) have addressed other issues raised by defendants in these motions at length, and found the arguments unpersuasive.

Second: Can any plaintiff establish a sufficient connection between the fossil fuel companies and climate impacts to survive a motion to dismiss? The standards for pleading (and proving) such a connection vary among jurisdictions and among causes of action, but the broad contours of defendants’ arguments are similar in the different cases. For one thing, defendants argue that climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, not by the production of fossil fuels, and so any claim against these companies is necessarily “indirect.” This raises difficult questions of spatial and temporal proximity to the harm, invokes the specter of the many unnamed third parties involved in producing the harm (including, as defendants repeatedly point out, plaintiffs themselves), and feeds into and off of defendants’ argument that they did not have “control” of the product at the time it “caused” the alleged nuisance. What’s more, defendants argue that their contributions, whatever they are, examined individually or taken together, cannot be shown to be a “but for” cause of climate change, due to the existence of competitors who arguably would have swooped in and produced whatever fossil fuels they did not and myriad other industrial and non-industrial factors that contribute to the problem. Again, panels at the Second and Fifth Circuit have concluded that causation in climate tort cases can be adequately pled to survive motions to dismiss, and those decisions may offer some guidance for how the courts respond here. But none of the judges in these cases are bound by those decisions.

It can be difficult to discern from a hearing where a judge will end up on a motion, but the upcoming arguments may begin to shed some light on which aspects of these cases Judge Alsup and Judge Keenan are most interested in or concerned about. Ultimately, wherever these judges do come out on these motions, the litigation will continue in other courtrooms, and the outcome will be far from settled.