By Romany Webb

On Wednesday May 17, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled a new Methane Reduction Plan, designed to advance the state’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. To date, state efforts have primarily focused on lowering emissions of carbon dioxide, which is the most prevalent greenhouse gas. The state has, however, recognized the need to also address methane emissions. Although methane is emitted in smaller quantities than carbon dioxide, it is much more potent, trapping up to 84 times more heat in the earth’s atmosphere in the first 20 years after it is released (on a per ton basis). Thus, according to the Governor’s office, “methane reduction is a key piece of New York’s policies to address the risks from climate change.”

On Wednesday May 17, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled a new Methane Reduction Plan, designed to advance the state’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. To date, state efforts have primarily focused on lowering emissions of carbon dioxide, which is the most prevalent greenhouse gas. The state has, however, recognized the need to also address methane emissions. Although methane is emitted in smaller quantities than carbon dioxide, it is much more potent, trapping up to 84 times more heat in the earth’s atmosphere in the first 20 years after it is released (on a per ton basis). Thus, according to the Governor’s office, “methane reduction is a key piece of New York’s policies to address the risks from climate change.”

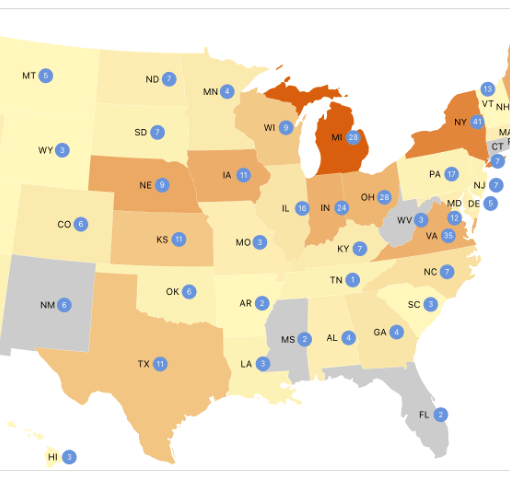

The Methane Reduction Plan targets the three major sources of methane emissions: (1) the oil and gas sector, (2) agricultural producers, and (3) landfills. It identifies 25 actions to be taken across the three areas by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (“DEC”), Department of Public Service (“DPS”), Energy Research and Development Authority, and Department of Agriculture. Interestingly, of those 25 actions, almost half are aimed at controlling emissions from the oil and gas sector. Those controls go significantly further than existing regulations at the federal level and may provide a model for other states looking to more tightly regulate oil and gas operations.

As previously reported on this blog, federal action on methane has moved backwards in recent months, with President Trump looking to remove many of the controls put in place by the Obama Administration. These include the new source performance standards adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) in June 2016 to limit methane emissions from new oil and gas facilities. (Those standards are summarized in my previous blog post here.) In his so-called “Energy Independence” Executive Order, President Trump directed EPA to review the standards, and revise or revoke them as appropriate. This followed an earlier decision by new EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt to withdraw an information request issued to oil and gas operators to obtain data needed to develop methane emissions limits for existing facilities. As discussed in a previous post, these developments suggest that further federal action to control the oil and gas sector’s emissions is unlikely, reinforcing the need for states to adopt their own controls.

New York’s Methane Reduction Plan is a good example of state-level action to curb methane emissions from oil and gas operations. It builds on the federal regulatory regime, requiring the DEC to implement EPA’s new source performance standards for new oil and gas facilities, while also directing it to develop additional regulations to control emissions from existing facilities, not covered by those standards. Similar regulations, applying to existing facilities, have recently been proposed or adopted in some other states (e.g. California, Colorado, and Pennsylvania). The regulations in each state focus primarily on controlling methane emissions from gas leaks, requiring operators to conduct frequent inspections at well sites and ensure prompt repair of identified leaks. New York is likely to adopt similar requirements. Indeed, the Methane Reduction Plan expressly calls for improved leak monitoring at well sites, and the prompt repair of leaks. The Plan goes further, however, also targeting leaks from the gas transportation system. That system, which consists of the network of pipelines and associated facilities used to move gas from production sites to customers’ premises, is regulated at both the federal and state levels. Federal regulation is limited to interstate pipelines (i.e., those crossing state boundaries), while intrastate pipelines are regulated by the states. As a result of this division of authority, the New York Methane Reduction Plan focuses on intrastate pipelines.

Currently, in New York and most other states, intrastate pipeline operators (“utilities”) are only required to repair leaks that are or may become hazardous. In determining whether leaks are hazardous, utilities focus on their proximity to buildings, rather than their size. As a result, leaks in isolated areas can be classified as non-hazardous and left unrepaired, even if they emit substantial methane. Seeking to prevent this, the Methane Reduction Plan directs the DPS to review the “current methodology and ranking system for repair of [non-hazardous] leaks . . . to ensure higher volume leaks are addressed by utilities, regardless of classification.” That’s something other states’ pipeline authorities should do as well. State authorities should also look at using their authority over pipeline rates to incentivize leak repair. In doing so, they may learn from the experiences of the DPS, which is required to take such action under the Methane Reduction Plan.

Pursuant to the New York Public Service Law, DPS regulates rates to ensure they are just and reasonable. Each utility is required to file a rate case with DPS outlining its forecast costs over the next regulatory period and establishing rates for the recovery of those costs. This approach may create disincentives for leak control as:

- while utilities can recover the costs of replacing leak-prone pipes in their rates, recovery often does not occur until the next rate case is filed, with the utility forced to carry the cost of its investment in the interim; and

- utilities can recover, in their rates, the cost of gas lost from the pipeline system due to leaks and other causes.

The Methane Reduction Plan requires DPS to address such disincentives and “[u]tilize rate cases to incentivize utilities to maintain a low backlog of leaks and replace leak-prone pipe.” Just how the DPS will do that remains to be seen. The fact that it will consider the issue at all is extremely significant, however. No other state has, to my knowledge, ever sought to address the problem of pipeline leaks through rate making. Now that New York has taken the first step, let’s hope others will follow suit.

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.