By Bernard E. Harcourt

Judith Butler and Stathis Gourgouris have brilliantly framed Foucault’s 1981 lectures on Subjectivité et vérité and Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling. Their comments pose three questions for our discussion:

- How individualized are we when we bind ourselves, given that we each are hardly alone in these acts but “bound to others who are doing the same act under a similar constraint,” as Judith Butler suggests?

- Is it possible to loosen the ties or deconstitute the way that we bind ourselves to truth through our avowals? And how would the unbinding work? Or, as Stathis suggests, how do we focus both on the binding and the opening?

- What makes sexual avowal different than every other avowal? Or to be less “passover-ish,” how do these avowals differ as we shift in time (historically) and between fields (the political, the sexual, etc…)?

To begin to frame these questions, it is important to place ourselves in our own proper historical period, because one of the most salient points in both Judith and Stathis’s comments is the importance of historicizing these moments of truth telling—whether it is in the Homeric poem, the Stoic examination of conscience, the 19th century asylum, or the courtroom with Robert Badinter in 1977—in order to ensure that we always remain deeply conscious of the political dimensions of those truth telling performances. So as to avoid, as Stathis just mentioned, depoliticizing our analysis.

Judith and Stathis have placed on the table, for our seminar, the breadth of historical moments of truth telling and the range of types of avowal:

- the sexual avowal

- the criminal avowal or inability to satisfactorily say who one is

- the avowal or not of madness

- the confessional and penitent avowals

- the vesperal examination of one’s daily actions and wrongdoings

- the political avowal of Antilochus.

I would like to add to that list—taking a more retrospective and equally political approach—the forms of avowal that mark our new digital mode of life, or, to borrow from the ancient Greek, our digital techniques of living, our tekhnai peri ton psifiakon bion or, from Latin, our own artes vitae digitalis.

***

I will begin, then, with a contemporary episode. It involves the following statement: “I mean, you know, you can call it what you want, but I am a truth teller, and I will tell the truth.” Those are the exact words, not of Antilochus, not of Oedipus, not of John the Ascetic. No, but let me repeat them. “I am a truth teller, and I will tell the truth.”

Those are the words of Donald Trump, yes, Trump, just the day before last, on Super Tuesday 2016, in his victory speech at his headquarters and resort in Palm Beach, Florida.

“I am a truth teller.”

When I heard those words, I could not but think of the epigraph to Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling—that marvelous passage from the philologist and anthropologist, George Dumézil’s book, Servius et la Fortune:

Looking back into the deepest reaches of our species’ history, ‘truthful speech’ [la parole vraie] has been a force few could resist. From early on, truth was one of man’s most formidable weapons, most prolific sources of power, and most solid institutional foundations. (WDTT, p. 28)

Or to a passage in the 1981 lectures, Subjectivité et vérité, on page 17 of the French edition, where Foucault states:

A discourse of avowal on an indissociable part of ourselves: it is around this question that we have to understand the problem of the relations “subjectivity and truth.”

Now, in these 1981 lectures on Subjectivity and Truth, Foucault would concentrate on sexuality—or rather aphrodisia since he is reading texts from Greek and Roman antiquity and Late Antiquity—in order to study the ancient arts of living. But his point extends to living in general – as we will see in the next lectures on the Hermeneutics of the Subject that generalize and extend the analysis beyond sexuality.

The role of avowal is central to our broader arts of living, our modes of existence today in this digital age. And not coincidentally, Trump’s speech is full of avowal. Not only of avowal, but of the courage of truth. Here is another statement he just made:

I’ll tell you what, it takes a lot of courage to run for president. I’ve never done this before. I’ve been a job-producer. I’ve done a lot of things but this is something I’ve never done, but I felt we had to do it.

Yes, notice the admissions, the confessions: “I’ve never done this before,” and how closely they are tied to courage. Avowal is a key elements of Donald Trumps campaign. Avowal and disavowal, especially on social media, on Twitter and Facebook.

On Super Tuesday, again, Trump repeatedly disavowed. This was concerning David Duke’s endorsement, so his relationship to the Ku Klux Klan… “Look, I disavowed. I disavowed…” Trump said in his Super Tuesday statement.

right after, when I reviewed it, I put out a tweet and I put out on Facebook that I totally disavow. […] And I disavowed then; I disavowed today on ABC with George Stephanopoulos, I disavowed again. I mean, how many times are you supposed to disavow? But I disavow and hopefully it’s the final time I have to do it. But if you look at Facebook and if you look at Twitter, right after the show I put out a statement because I want everybody to be sure.

Earlier, on CNN, Trump said “”I’ve disavowed David Duke all weekend long on Facebook and Twitter.” On Facebook and Twitter: that is telling—and I will come back to it in a moment.

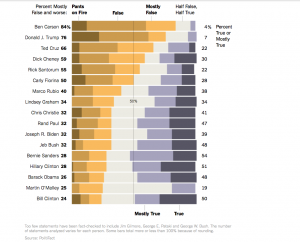

Now, despite claiming to be a truth-teller, Donald Trump’s record on truth is poor, the second worse this election season only to Ben Carson—who is no longer in the running. So that makes Trump perhaps the worst truth-teller in truth.

According to Angie Holan at PolitiFact, the political fact-checking website, “Donald J. Trump’s record on truth and accuracy is astonishingly poor. So far, we’ve fact-checked more than 70 Trump statements and rated fully three-quarters of them as Mostly False, False or “Pants on Fire” (we reserve this last designation for a claim that is not only inaccurate but also ridiculous).”

76% of his checked statements (n = 70) are false or mostly false or worse. Only 7% are true or mostly true, with the rest half-true, half-false. So the ratio there is 76% on the false side versus 7% on the true side.

To give you a comparison point or two:

- President Obama, who “has the distinction of being the most fact-checked person by PolitiFact — by a wide margin, with a whopping 569 statements checked,” comes in at 26% on the false side to 48% on the true side.

- Ted Cruz 66% on the false side to 22% on the true side

- Marco Rubio: 40 to 38

- Hillary Clinton: 28 to 51

- Bernie Sanders: 28 to 54. In fact, of the 17 politicians in their study, Sanders was the only one with a majority of true or mostly true statements.

- Bill Clinton had the lowest percentage of false or mostly false statements, at 24%, with 50% true or mostly true. (To remind you, the reason we are not at 100% is the gap in the middle of half-truth, half-false).

To give you a sense of the truthfulness of our politicians, here is a graphic from the Times:

Now I am sure that, however non partisan PolitiFact may be, Donald Trump would question their objectivity—probably deploying a power-knowledge argument that he would attribute to Foucault if he were here.

And perhaps because of power-knowledge, so many Americans believe Trump. Believe that he is telling the truth. That is his draw it seems. At least if you listen to the man or woman on the street who supports Trump:

- “He tells it like it is.”

- “He says what he means.”

- “I honestly believe he is telling the truth.”

- “He is funding his own campaign. Nobody owns him.”

This last theme is important. The idea that because Trump is funding his campaign—or more appropriately, lent his campaign about 17 million dollars—he is not beholden to anyone. He is his own man. He can say what he believes. He does not need to bend to anyone. He has no political or spiritual guide but himself.

He is not engaged in an act of obedience. Trump says this himself: “I am self funding my campaign. I tell the truth.” Actually, let me give you the full quote here: “I don’t lie. I mean I don’t like. In fact, if anything, I’m so truthful that it gets me in trouble, OK? They say I’m too truthful. And, no I don’t lie. I don’t lie. I’m self-funding my campaign. I tell the truth.”

The fact that he is bankrolling himself, to many Americans, does not raise questions about our campaign finance laws or the corrupt nature of campaign finance today—but rather it says something about his truthfulness. He does not owe anybody anything. He is not in a condition of obedientia. Not at all like that other figure in history that Foucault describes on page 136 of Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling:

the example concerns a woman, a wealthy woman who had decided to renounce life and had accepted as the form of renunciation to become the servant of someone else. She came upon a mistress who was just towards her—not indulgent, but just. She therefore asked the bishop to find her an old and particularly unjust and cantankerous woman whose caprices she followed so well that she achieved salvation precisely due to the fact that the person she served was unjust.

No, he is not obedient, nor does he present himself as subservient. Not like Abbot John, who, Foucualt tells us:

took the path of saintliness as the disciple of a monk who, one day, told him to plant a dried stick in the desert far from any well or spring. He told him to water it twice a day, promising him that the stick would blossom (this is an addition from a later version, but no matter). No need to tell you how the story ends: at the end of the year, the stick was still withered. The master criticized his disciple Abbot John for not having watered it sufficiently, and so he watered it for another year, and of course the tree finally blossomed.

No, Trump can tell the truth because he is funding his own campaign. He does not serve anyone. He does not obey another, only himself and his truth, he tells us.

***

I have emphasized Donald Trump in part to de-romanticize truth-telling and to re-politicize it. Too often, we associate truth-telling with our favorite heroes, like Antilochus, or with tragic heroes, like Oedipus. We focus on vesperal examinations of conscience, or on the performativity of the words of Pierre Rivière or Patrick Henry—the excluded other, the mad. We gravitate toward the parrhesiaste who we admire or the courage of truth. But it is important to remember, lest we get too romantic, that Donald Trump too claims the position of the truth teller and, for many, he is the parrhesiaste.

So with this context in mind, let me begin to address the three questions raised in Judith Butler’s and Stathis Gourgouris’s brilliant comments. What I would suggest, perhaps to launch the discussion, is that we may need to write a new chapter on avowal in the digital age. As I have tried to establish in The Expository Society, power circulates differently in the digital age. Donald Trump’s presidential campaign is a reflection of that. Trump has succeeded in drawing attention to himself precisely because he is a master of reality TV and a great communicator on social media.

In this digital age, Trump has reached such a wide audience in large part because of his Tweets and reality TV snippets. The cable news network CNN captures this best in a pithy lead to a story titled “Trump: The social media president?”:

FDR was the first “radio” president. JFK emerged as the first “television” president. Barack Obama broke through as the first “Internet” president.

Next up? Prepare to meet Donald Trump, possibly the first “social media” and “reality TV” president.

Trump’s campaign is somewhat unique in this sense and his success has been related, in my opinion, to his command of reality TV—his performances on The Apprentice and Celebrity Apprentice. Trump has become such a social media phenomenon, that even when he did not participate in one of the Republican debates, that very night he dominated the other candidates in terms of searches on the Internet and social media postings. And thanks to John Oliver, the second most searched presidential candidate these days is Donald Drumpf.

But this is merely a reflection of a larger issues: we all are now functioning in a new political reality of public avowals disseminated far and wide. This is having an effect on all the different forms of avowal, including important implications for sexual avowal. Our more curated sexual avowals today are affected by the digital media. So for instance, in contrast to anonymous chat rooms, “public proclamations of non-mainstream or gay sexual orientations seem[s] to be rare on Facebook”—or at least, more infrequent. According to studies, it is more common and disproportionally so to read mainstream, heterosexual displays of affection like this one, by a female student in a Facebook study: “I am currently married to a man named xxx [real name was provided originally but removed here to protect privacy]. He is the reason I wake up ever morning with a smile on my face & the reason why I look forward to living another day. He is my lover & best friend.” Apparently, only recently are people beginning to post about getting divorced on social media like Facebook. Still today it is relatively rare to see “the documentation of strife, anxiety, discord or discontent.”

And it affects us, everyone of us, right here as well. This very evening, our own truth telling … it is being digitized and broadcast, simultaneously, live, on webcam, around the world. We are communicating, right now, with colleagues, friends, strangers, with people in Australia, New Zeeland, Hungary, Brazil, Paris, Slovenia, Korea, Turkey, the Palestinian Territories. Yes, in the last livestream report from our last seminar, there were two colleagues in the Palestinian Territories participating in the seminar.

We have Twitter repeating our truth-telling and Facebook comments. We live in a new world, one in which we are exposed and exposing ourselves – and I do not think we can avoid our own complicity in the shifting sands of avowal.

So, to launch the discussion, we might flesh out the original three questions with a series of other strands:

- Could it be that the increased and pervasive publicity of our digital age has rendered our avowals more thin, perhaps in a useful way, in a way that might loosen the bonds that tie us to our truths? It is, after all, far more easy today to avow or disavow to a huge multitude. Trump can do it in a flash to 6.58 Million followers on Twitter. So on Feb. 28th, Trump would tweet, regarding David Duke: “I disavow.” A disavowal that would get 5.7 thousand retweets and 11 thousand loves, likes, hearts, or favorites, whatever you want to call them. With even more on Facebook – where his official page has something like 6 million likes.

- Are these proliferating avowals in different relation to the other: There is no Dr. Leuret, no judge doing any sentencing, no spouse at the end of that vow. Are these cheaper avowals? Are they less bound to institutional structures? Are we now facing a more instrumentalized form of avowal on-line?

- Do we need to sever these new forms of avowal from the core of truly subjective avowals—the religious confessions, the spiritual guidance? But what is this “truly subjective” that I just mentioned?

- How does Antilochus’ political quasi-avowal differ, in any meaningful way from Donald Trumps? Antilochus, you will remember, was fooled by his youth, or so he said. But in the process, reinstituted, I would say, in an even more solid way, the social hierarchy of seniority and heroism of ancient Greece. His purported truth-telling established a stronger order. Is it any different with Trump today?

Maybe we should end, then, where we began, once again with Dumézil:

Looking back into the deepest reaches of our species’ history, ‘truthful speech’ [la parole vraie] has been a force few could resist. From early on, truth was one of man’s most formidable weapons, most prolific sources of power, and most solid institutional foundations.

How have we arrived at a time in which Trump’s claims of truth-telling stand (to his supporters) in stark contrast to a political field mired in dishonesty and deceit? It seems that his acts of truth-telling are only powerful to the extent that other candidates and politicians are not able to lay claim to the truth in the same way (for a multitude of reasons, campaign financing is a very important one you mentioned). How is this field of dishonesty formed in relation to Trumps avowals? Does this field/arena/collective assignment of dishonesty preceded the truth telling avowals of trump or does the avowal bring it into existence (by marking it as other)? Historically, how has the power of the truth depended on or been shaped by an opposite yet relational dishonesty or untruth? Has the truth only and always been connected with a dishonesty or untruth which with to be contrasted or is this a modern phenomenon?

1. every avowal is the opportunity of its own undoing (deniability)

2. only the truth if spoken is a specific and enforced language (hearability)

3. avowal exposes the skeleton of discourse and nothing else (reflexivity)

4. a dangerous subject : more knowing about the law than by it (desirability)

5. when do we all start yelling? (potentiality)