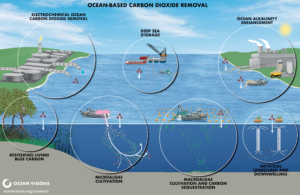

The Sabin Center wrapped up Climate Week NYC last Friday with an event exploring the opportunities and challenges posed by ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR). As evidenced by the 150-plus people in attendance, ocean CDR is attracting growing attention as a possible climate change mitigation option. It is not hard to see why. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently concluded that CDR will be needed, alongside deep emissions cuts, to limit global warming to 1.5 to 2oC in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement. There is growing consensus that a variety of CDR approaches will be required. Ocean-based approaches, such as ocean fertilization and ocean alkalinity enhancement, appear to hold promise. But, as noted in a 2021 National Academies of Sciences (NAS) report, key questions remain about their efficacy, benefits, and risks. The NAS report called for development of “a research program for ocean CDR,” and identified priority research investments totaling approximately $1.4 billion. Others have advocated for even larger investments in research (see here for an example).

Funding is, of course, essential to advance ocean CDR research but other factors could also have a major bearing on future projects. As previously reported on this blog, ocean CDR research could implicate various international and domestic laws that might affect whether, when, where, and how projects take place. Among the international legal instruments that might apply to ocean CDR are the 1972 Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention or LC) and the 1996 Protocol to the Convention (London Protocol or LP). Parties to those instruments are set to meet in London next week—from October 2 to 6—to discuss the regulation of so-called “marine geoengineering activities” (among other things). The outcome of those discussions could have a major bearing for future ocean CDR projects.

Briefly, by way of background, both the LC and LP aim to limit ocean dumping. The LC was adopted first in 1972. Twenty years later, in 1992, the parties agreed to the LP which was intended to update and eventually replace the LC. However, before the LC can be replaced, all of the countries that are party to it must ratify the LP. Many haven’t yet done so. The U.S., for example, is a party to the LC but has not yet ratified the LP.

Both the LC and LP require parties to adopt domestic laws to regulate the “dumping” of “waste and other matter” at sea. Dumping is defined broadly to mean “the deliberate disposal of waste or other matter at sea from vessels, aircraft, platforms, or other manmade structures.” Legal scholars, myself included, have long debated whether and when this definition might encompass ocean CDR activities that involve adding materials to the ocean.

For example, would the definition capture ocean fertilization projects in which vessels discharge iron or other nutrients onto the surface of the water, with the goal of stimulating the growth of phytoplankton that uptake carbon dioxide as they grow? What about ocean alkalinity enhancement projects that involve the discharge of alkaline substances (e.g., ground rock) into the ocean? What about artificial upwelling / downwelling projects that use long vertical pipes to cycle water between the deep ocean and the surface? In each case, something is added to the ocean—nutrients in ocean fertilization, ground rock in ocean alkalinity enhancement, and pipes in artificial upwelling / downwelling. But the projects arguably don’t involve “deliberate disposal.” After all, materials are not being added to the ocean to get rid of them, but rather for the purpose of CDR.

In both the LC and LP, the definition of “dumping” excludes the “placement of matter for a purpose other than mere disposal thereof, provided that such placement is not contrary to the aims of” of the LC / LP. What this means for ocean CDR has, too, been hotly debated.

Some clarity emerged in 2008, when the parties to the LC and LP adopted a resolution, dealing with ocean fertilization. The resolution stated that ocean fertilization projects conducted for research purposes “should be regarded as placement of matter for a purpose other than mere disposal, and thus will not be classed as dumping, provided they are “not contrary to the aims of the” LC / LP. The parties subsequently, in 2010, adopted a framework for assessing research projects. The framework provides that countries “should” only conclude that research is not contrary to the aims of the London Convention and Protocol, and thus not dumping, if “conditions are in place to ensure that . . . environmental disturbance would be minimized and the scientific benefits maximized.”

The 2008 resolution and 2010 assessment framework are not legally binding. But, in 2013, the parties to the LP adopted an amendment that is intended to be. The amendment deals with the “placement of matter into the sea” for the purpose of “marine geoengineering,” which the parties defined to mean:

“a deliberate intervention in the marine environment to manipulate natural processes, including to counteract anthropogenic climate change and/or its impacts, and that has the potential to result in deleterious effects, especially where those effects may be widespread, long lasting or severe.”

The amendment requires parties to the LP to prohibit “the placement of matter into the sea” in connection with listed marine geoengineering activities “unless the listing provides that the activity . . . may be authorized under a permit.” Only ocean fertilization has been listed so far. The listing only allows for the issuance of permits for ocean fertilization research (not deployment) and only if certain requirements are met. Some in the ocean CDR community have expressed concern that the requirements are difficult to meet and thus could hinder needed research. Particular concerns have been expressed about a requirement that research not result in any “financial and/or economic gain,” with some arguing that this could prevent privately-funded research that is intended to advance commercial interests.

The 2013 amendment has not yet entered into force. For that to happen, it must be ratified by two-thirds of the parties to the LP. That seems unlikely in the near future given that, in the 10 years since the amendment was adopted, only six of the 55 parties to the LP have ratified it. Moreover, even if (or when) the amendment does enter into force, it will only be legally binding on LP parties. Countries, like the U.S., that are only party to the LC won’t be legally bound by the amendment. It might still influence their actions, however.

In June this year, a legal committee appointed to advise the LC and LP parties on marine geoengineering issued a draft statement on the 2013 amendment. While the exact wording is still to be finalized, as shown by the inclusion of text in square brackets, the draft statement emphasizes the importance of the 2013 amendment, not only for parties to the LP but also for non-parties. According to the statement:

“Parties to the LP who accepted the 2013 amendment [shall][should] refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose of the amendment pending its entry into force . . . Parties to the LP who have not yet accepted the amendment, and Parties to the LC are strongly encouraged to refrain from such acts.”

The legal committee also suggested that the 2013 amendment could be “provisionally applied” before it enters into force. This has happened with other amendments to the LP. For example, in 2019, the parties to the LP agreed to allow the provisional application of a 2009 amendment allowing the export of carbon dioxide for sub-seabed storage (more on that here). The parties might similarly agree to provisional application of the 2013 amendment.

There is also talk about possibly expanding the range of activities that are listed, and thus regulated, under the 2013 amendment. As noted above, currently, the amendment only applies to ocean fertilization. However, early last year, GESAMP—a group of independent scientific experts that advises the UN system on marine protection—identified seven other activities “that the [LP] parties might wish to consider for listing.” A scientific group advising the parties subsequently published a short-list of four activities that they said deserve “priority evaluation.” Two of them are ocean CDR activities, namely (1) “enhancing ocean alkalinity” and (2) “macroalgae cultivation and other biomass sequestration including artificial upwelling.” The latter category includes seaweed cultivation and sinking, which is gaining increasing attention as a potential CDR technique. (The other two activities listed for priority evaluation involve solar radiation management.)

For the past several months, the scientific group and legal committee have been evaluating the activities, so as to inform the parties’ decision on whether to list them under the 2013 amendment. The results of that evaluation were published in June (see here for the scientific group’s report and here for the report of the legal committee).

Interestingly, the scientific group concluded that the broad category of “enhancing ocean alkalinity” should be divided into three sub-categories based on “how alkalinity is produced and where the [carbon dioxide] drawdown takes place.” Specifically, the group distinguished between:

“A) Adding alkaline material (natural or artificial substances) to the marine environment;

B) Adding alkaline material to the marine environment that is produced by electrochemical approaches; and

C) Controlled alkalinisation in reactors with discharge of a [carbon dioxide]-equilibrated or alkaline solution to the marine environment.”

This may seem like a purely scientific distinction but it has important legal consequences. Indeed, the legal committee determined that while activities falling with sub-groups (A) and (B) above could be listed under the 2013 amendment, those within sub-group (C) may fall outside the scope of the amendment. This is because the amendment only applies to activities that involve “the placement of matter at sea” for the purpose of “marine geoengineering” (as defined above). According to the legal committee, activities in sub-group (C) above that involve the discharge of “equilibrated seawater” (rather than an alkaline solution) do not qualify because the discharge “is merely an act of disposal with no other purpose, and no intention to manipulate natural processes.”

The legal committee also considered whether macroalgae and artificial upwelling projects might qualify for listing under the 2013 amendment. With respect to the former, the committee distinguished between projects that involve growing and sinking seaweed in the ocean, and those in which seaweed is grown and then harvested for use on land. Ultimately, however, the committee concluded that both classes of projects would qualify for listing under the 2013 amendment. So too, in the committee’s view, would artificial upwelling projects. According to the committee, in each case, material is placed in the ocean for the purpose of manipulating natural processes so as “to remove carbon” and that placement “has the potential to result in deleterious effects.” While the legal committee did not elaborate on those potential effects, they are discussed in detail in a report published by the scientific group (see here).

It remains to be seen what the parties to the LP will do with this information but it is sure to be discussed at next week’s meeting in London. Regardless of the outcome of those discussions, it is likely that some countries will enact domestic laws to control ocean CDR and other “marine geoengineering” activities.

Germany has already done just that. In 2020 and 2021, Germany amended two existing laws—1998 High Seas Dumping Act and 2009 Water Management Act—to regulate marine geoengineering activities. The German delegation to the IMO recently reported that, as a result of the amendments, “currently all types of marine geoengineering activities except ocean fertilization . . . research projects [are] prohibited” under domestic law. Australia might do something similar. A bill currently before the Australian parliament would, if enacted, prohibit listed marine geoengineering activities without a permit. Like the 2013 amendment to the LP, the Australian bill currently only lists ocean fertilization, but could be expanded to apply to other ocean CDR activities in the future.

The situation is a little different here in the U.S. The LC is implemented domestically in the U.S. through a federal statute known as the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which is responsible for administering the MPRSA, has concluded that it may apply to some ocean CDR activities. It won’t apply to all of them, however. As the U.S. delegation to the IMO recently reported, the MPRSA will only apply to projects that involve “the deposition of material in the ocean,” if the project developer does “not intend, anticipate or prepare to recover the material form the ocean as part of the project.” So, for example, ocean CDR projects that involve the cultivation and harvest of seaweed for use on land may not be captured. Nor may artificial upwelling projects that involve only temporary installation of pipes in the ocean (i.e., that are later removed). As previously reported on this blog, those activities might be subject to other domestic laws, but exactly how and when those laws will apply is often highly uncertain.

The one thing that is clear is that law—both international and domestic—will have a huge bearing on future ocean CDR research. As the 2021 NAS report noted, “[d]eveloping a clear and consistent legal framework is essential to facilitate research . . . while also ensuring that projects are conducted in a safe and environmentally sound manner.” The Sabin Center recently published a model law that aims to achieve those dual goals by, on the one hand removing inappropriate barriers to research, and on the other still maintaining appropriate safeguards to minimize environmental and other risks. It remains to be seen whether the U.S. and other countries can achieve the right balance.

Note: A video recording of the Climate Week NYC event on ocean CDR, which the Sabin Center co-hosted with Ocean Visions, is available here.

Romany Webb

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.