Earth Day is an opportunity to celebrate the awe-inspiring wonders on this planet — a place full of biodiversity hotspots, from lush rainforests to scenic mountain ranges, home to rich, endemic species. These pristine, ecologically unique landscapes are increasingly threatened by human-caused stressors such as greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to the harmful impacts of climate change on people and the planet.

Tackling the climate crisis requires a multifaceted approach. We know we must rapidly and dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including through a just transition to a renewable-energy driven economy. We must also better prepare for climate change impacts that are already occurring or expected in the future. In recent years, climate litigation has increasingly been used to push governments and others to reduce emissions and invest in adaptation measures (see the Sabin Center’s climate litigation databases here). International agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, and domestic legislation in the U.S. and elsewhere, have also been important in driving change.

While progress is being made, there is still a lot to do. The IPCC has said that, in addition to reducing emissions, it will likely also be necessary to draw greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere to mitigate climate change. The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, a joint center of the Columbia Climate School and the Columbia Law School, has been exploring various ways of doing that, including through “blue carbon” approaches. Blue carbon is carbon captured by ocean and coastal ecosystems. In this post, we will focus specifically on ocean-based carbon dioxide removal and sequestration, also known as “ocean CDR”.

The ocean covers 70% of the Earth’s surface and is a major carbon sink. Through natural processes, the ocean has absorbed around 25% of human-produced carbon dioxide emissions to date, and could take up even more in the future. Uptake of carbon dioxide by the ocean occurs through both biological processes — e.g., via carbon sinks like phytoplankton and whales — as well as non-biological ones.

Ocean-based Carbon Dioxide Removal Techniques

The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law has published a series of four white papers exploring the legal issues associated with a range of ocean carbon dioxide removal strategies, which are outlined below. These white papers, written by Romany Webb, Korey Silverman-Roati and Michael Gerrard, provide the most comprehensive analysis of the legal aspects of ocean CDR. These same authors also published a book on “Ocean Carbon Dioxide Removal for Climate Mitigation: The Legal Framework” this week. For the purposes of this post, we will give a broad overview of these techniques, as well as the potential benefits and risks associated with them.

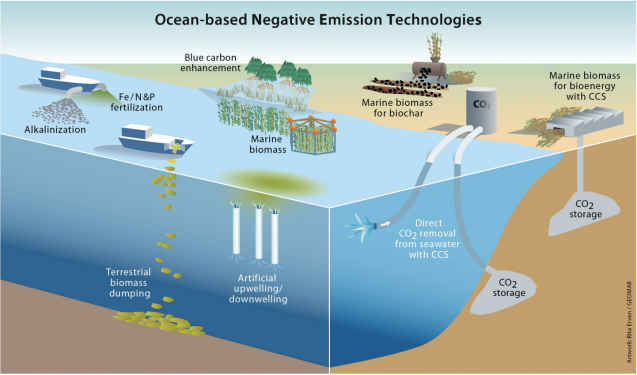

- Artificial upwelling and downwelling: This technique consists of using vertical pipes to cycle nutrient-rich water upward from depth to the surface, where it could stimulate the growth of phytoplankton. The phytoplankton take in CO2 during photosynthesis, then pipes would send the carbon-rich water from the surface down to depth.

- Seaweed cultivation (also known as seaweed farming): This method consists of growing or cultivating seaweed, also known as macroalgae, which converts dissolved carbon dioxide into organic carbon as it grows through photosynthesis. The seaweed may then be harvested (e.g., for use as bioenergy or for low-carbon products such as packaging materials made out of seaweed) or sunk into the deep ocean for carbon sequestration. How long can the biomass be sequestered for? That depends on a variety of factors, including the location of the sinking. Biomass could potentially be sequestered for more than 500 years if sunk below 1,000 meters in some parts of the ocean, but the length of time would be considerably less if the biomass were sunk in shallower waters. The environmental co-benefits include lower levels of ocean acidification, among others.

- Ocean fertilization (also known as microalgae cultivation): In this technique, iron, nitrogen or phosphorus is discharged into the surface of the ocean to stimulate the growth of phytoplankton. The hope is that phytoplankton will take in carbon dioxide and then die and sink, carrying the carbon they contain into the deep ocean or seafloor sediment for long-term storage. Some scientists speculate that the benefits could include increased growth rate of fish populations due to enhanced phytoplankton productivity, while others worry that this could lead to harmful algal blooms or that it could divert nutrients from other locations.

- Ocean alkalinity enhancement (also known as enhanced weathering): This method involves adding ground limestone or other alkaline rock into ocean water. The addition triggers a series of chemical reactions, which enables the ocean to absorb additional CO2 from the atmosphere. The materials needed for this method would be mined on land and then spread onto beaches or added to seawater via pipelines or ships. This method has the potential to drastically accelerate natural mineral weathering processes, which absorb CO2 but normally take thousands of years. Just like seaweed cultivation, this can also lead to decreased ocean acidification. Potential risks include increased levels of toxic metals and other minerals with largely unknown effects on biodiversity.

The Laws of the Ocean

Determining how and where these ocean carbon dioxide removal techniques would work best, what risks they pose and how best to ensure the ocean environment is protected, is subject to ongoing research. Most of the techniques have not yet been tested at scale and require significantly more investigation before we can decide whether and how they might be used to fight climate change.

While there are international and domestic laws governing ocean-based activities, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the London Convention and Protocol, there remains a need to develop robust legal frameworks specifically tailored to ocean carbon dioxide removal research.

With this in mind, the Sabin Center has developed and recently released model legislation to advance safe and responsible ocean CDR research in the United States. According to a recent opinion piece authored by Korey Silverman-Roati and Romany Webb, the goal of this model legislation is to facilitate safe and responsible ocean CDR research, including by “establishing permitting authority in a single federal agency, designating preferred zones for ocean CDR research with streamlined permitting, as well as calling for a balance between climate goals and environmental risks.”

When developing ocean CDR research projects in the U.S., a high priority must be given to involving Native American Indigenous tribes, states, and the public in these decision-making processes. If you are interested in learning more about the significance of this model legislation, join this webinar hosted by Ocean Visions and featuring the Sabin Center Deputy Director Romany Webb.

The larger question with respect to these ocean-based carbon dioxide removal techniques, particularly the ones utilizing labor and cost-intensive technologies, is: Can these approaches make a meaningful contribution to combating climate change? And do the economic, social, and environmental benefits and risks posed by these activities justify their use? Until we have more definitive answers to these questions, we shouldn’t lose sight of taking collective action to drastically cut existing emissions.

Can we avoid the worst impacts of climate change? That depends on how fast we act. Our Earth needs us to ramp up climate action now.

This post was originally published on Columbia Climate School’s State of the Planet here.

* I would like to thank Romany Webb for her valuable guidance on the content of this blog post.

Tiffany is the Communications Associate at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.