O n Monday, April 17, 2023, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit handed down a decision in California Restaurant Association v. City of Berkeley. The court overturned a District Court ruling to invalidate a Berkeley, California, prohibition on natural gas infrastructure in newly-constructed buildings. Berkeley’s so-called “natural gas ban” was the first local ordinance in the country to effectively require all-electric construction of new buildings.

n Monday, April 17, 2023, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit handed down a decision in California Restaurant Association v. City of Berkeley. The court overturned a District Court ruling to invalidate a Berkeley, California, prohibition on natural gas infrastructure in newly-constructed buildings. Berkeley’s so-called “natural gas ban” was the first local ordinance in the country to effectively require all-electric construction of new buildings.

Since 2019, more than seventy local and state jurisdictions have followed Berkeley’s lead in requiring or strongly incentivizing all-electric or fossil-fuel-free new buildings, with more considering similar approaches. Electrification is a critical component of building decarbonization, and local governments are taking a leading role in this policy space. But local governments operate under varying legal parameters, and the Ninth Circuit decision has different implications for different building electrification requirements depending on location, legal landscape, and policy approach.

While a handful of local prohibitions fall within the Ninth Circuit decision’s scope, many more do not. In exploring what the CRA v. Berkeley decision does and does not say, local governments can better understand that many of them have options for electrifying new buildings.

CRA v. Berkeley: Berkeley’s Ordinance Preempted by U.S. Energy Policy & Conservation Act

Following Berkeley’s 2019 gas prohibition ordinance, a trade group representing members “interested in opening a new restaurant or in relocating a restaurant to a new building in Berkeley,” brought suit against the city. While the California Restaurant Association made both state and federal claims, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California substantively heard only the federal claims asserting preemption by the federal Energy Policy & Conservation Act, or EPCA, which preempts state and local governments from setting standards “concerning the energy efficiency, energy use, or water use of” products regulated by EPCA. In 2021, the District Court ruled that the Berkeley ordinance was not preempted by EPCA, rejecting the notion that EPCA preempts local ordinances that do “not facially address any of those [energy conservation or energy use] standards.”

Yesterday, the Ninth Circuit reversed the District Court decision, invalidating Berkleley’s ordinance and holding it preempted by Section 6297(c) of EPCA. Under EPCA, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) sets energy conservation standards for many common building appliances such as furnaces, HVAC systems, and hot water heaters (a few of many EPCA “covered appliances”), and state and local governments are mostly preempted from setting energy standards for those same pieces of equipment. The Ninth Circuit interpreted EPCA’s preemption provision to have a broader scope than asserted by both Berkeley and the U.S. Department of Energy, which is tasked with implementing EPCA and its preemption provisions. Rather than adopt the DOE view that EPCA preemption does not “prevent States and localities from adopting health and safety regulations that indirectly affect the quantity of energy or water used by” an EPCA covered-appliance, the Ninth Circuit held that EPCA preempts state and local standards that interfere with “the end-user’s ability to use installed covered products at their intended final destinations” (emphasis in original). The court further wrote that “by using the term ‘concerning,’ Congress meant to expand preemption beyond direct or facial regulations of covered appliances.” This is in contrast to the District Court, which had concluded that EPCA preemption should be interpreted as limited in order to avoid “sweep[ing] into areas that are historically the province of state and local regulation.

Berkeley has not yet said whether it will appeal the Ninth Circuit’s ruling. Even if the decision stands, it applies only in the Ninth Circuit, which encompasses Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Moreover, it applies only to the Berkeley ordinance and, effectively, those that are structured similarly. Local governments have structured or are considering structuring all-electric construction policies in a variety of ways, some of which remain untouched by the Ninth Circuit ruling. Options that remain available to local governments are addressed in the next section.

Beyond Berkeley: Local Governments Have Building Electrification Options

In enacting its ordinance, Berkeley relied on its police powers, or its authority to govern with respect to health and safety, to prohibit the extension of natural gas piping to new buildings. In contrast, many other jurisdictions — in California and beyond — used their building code authority to require or incentivize all-electric construction. New York City took a third approach, enacting an air emissions standard for new buildings that was silent on the energy performance of any building or EPCA-covered appliance. Each of these approaches remains an option to at least some local governments looking to electrify new construction. In addition, local governments retain any authority over natural gas distribution they may be delegated by their states.

Building code authority: While EPCA broadly preempts many state and local energy conservation standards for appliances, the law also contains a statutory exemption to EPCA preemption for state and local building codes. For local governments with building code authority, building code requirements may include standards that relate to the energy efficiency or energy use of EPCA-covered appliances if the codes meet seven conditions, namely that the code (1) “permits a builder to… select[] items whose combined energy efficiency” meet an overall building energy target; (2) does not specifically require any EPCA-covered appliance to exceed federal standards; (3) offers options for compliance, including an appliance that exceeds federal standards, on a “one-for-one equivalent energy use or equivalent cost basis”; (4) bases any baseline building design used by the code on a building with covered products that do not exceed federal standards; (5) offers at least one “optional combination[] of items” that does not exceed federal standards for any covered appliance; (6) the frames any energy target as a total for the building; and (7) uses EPCA-specified test procedures for determining the energy consumption of covered products.

To put it more simply, in order to satisfy the building code exception to EPCA preemption, building codes must offer options for builders to install appliances that pass muster under EPCA (i.e., can be fueled by natural gas), and must base these options on a defensible “one-for-one” basis. One way to accomplish this is to effectively require builders to build either all-electric or with fossil fuels but to a more stringent efficiency standard. The City of Ithaca, New York, for example allows buildings to achieve compliance with its 2021 Energy Code Supplement through a “prescriptive” compliance pathway under which buildings have to achieve six points to comply. Two points may be earned through the use of electric air source heat pumps with no fossil fuel back-up, making electrification a straightforward way to accumulate compliance points. Alternatively, buildings may follow a “performance” compliance pathway with a more stringent efficiency standard. (This post is not expressing a legal opinion on Ithaca’s code.) The Ninth Circuit expressly states that the building code exception is an acceptable way to avoid EPCA preemption.

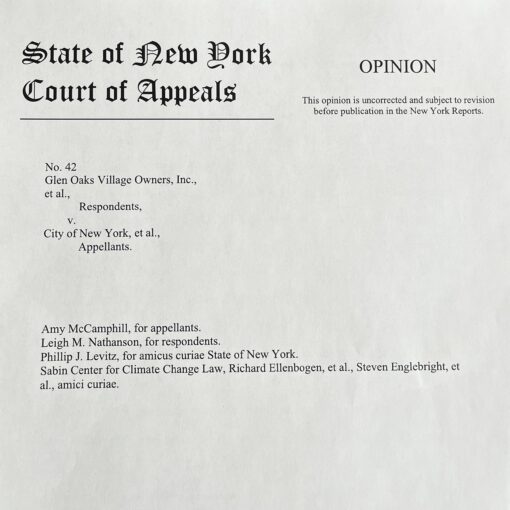

Air emissions standard: New York City’s approach to building electrification currently stands alone in prohibiting newly constructed buildings from “combust[ing] any substance that emits 25 kilograms or more of carbon dioxide per million British thermal units of energy.” This approach should not be preempted by EPCA; EPCA pertains to energy standards, while New York City’s standard is an air emissions standard. Air pollution is governed at the federal, state, and sometimes local levels, and the relevant federal statute is the U.S. Clean Air Act, not EPCA. Legal questions remain in connection with the air emissions standard approach, particularly with respect to limitations of state law, but many local governments retain authority to regulate air pollution to some degree. (New York is located in the Second Circuit, further insulating it from the CRA v. Berkeley decision.)

Police power: Within the Ninth Circuit, a health- and safety-based prohibition on natural gas piping in buildings is blocked by the court’s ruling. However, the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning does not automatically apply to state or local governments in other areas of the country, and there are reasons to argue that the Ninth Circuit’s reading of EPCA preemption is overbroad. Local governments outside of the Ninth Circuit may choose to adopt an approach similar to Berkeley’s and, if sued, make their own case for the lawfulness of the approach (note that a circuit split would increase the likelihood of the Supreme Court taking the case, a strategy approach not to be taken lightly).

Natural gas distribution: While beyond the scope of the blog post, and subject to close review with respect to state law, local governments often have some authority over natural gas distribution at the local level, through franchising, utility siting control, and more. The Ninth Circuit does not dispute this local authority, noting that its “holding doesn’t touch on whether the City has any obligation to maintain or expand the availability of a utility’s delivery of gas to meters.”

Takeaways

While the Ninth Circuit decision does impact some aspects of local authority to electrify buildings, it is far from a knockout blow. Local governments with building code authority retain that authority, and are well-advised to pay close attention to the contours of the building code exception to EPCA preemption. Those with air pollution authority could pursue the New York City approach; EPCA does not preempt air emissions standards. Local governments may also wish to work on their own or with their states to regulate natural gas distribution. Further, the decision applies only in the Ninth Circuit, and does not further limit local governments in other circuits. Finally, Berkeley may yet appeal the decision, meaning that this is not the last word.

Local governments should consider the CRA v. Berkeley decision in the broader context of the many legal parameters — obstacles and opportunities — that govern different jurisdictions differently. Many local governments have no more or less legal authority than they did before the Ninth Circuit issued its ruling, and, at least in some cases, may actually be able to use the Berkeley decision to bolster their chosen building electrification approaches.

Amy Turner is the Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.