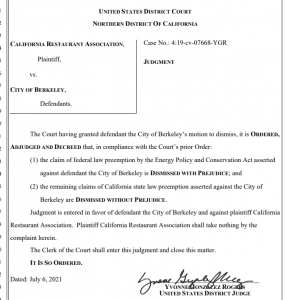

Yesterday, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California issued a long-awaited decision in California Restaurant Association v. City of Berkeley. The decision essentially – and subject to possible appeals – answered in the negative the question of whether Berkeley’s first-in-the-nation prohibition on natural gas hookups to newly-constructed buildings (often termed a “natural gas ban”; herein referred to as the “Berkeley Ordinance”) was preempted by the U.S. Energy Policy & Conservation Act (“EPCA”). But, more than that, the decision offers guidance with respect to other questions on local policymakers’ minds: What, exactly, does EPCA preempt? Does the phrase “local regulation… concerning the energy conservation [or] energy use” capture a huge range of policies that effectively, but indirectly, preclude the use of an energy type, no matter how far from direct energy “standards” they may be? The District Court’s decision indicates that EPCA preemption is not so far-reaching as some had argued.

To take a step back, EPCA – a sprawling law passed in the 1970s meant to conserve energy in the face of the oil crisis – directs the U.S. Department of Energy to set energy efficiency, energy use and water use standards for a range of “covered appliances,” including many large building systems like furnaces, water heaters and HVAC systems. In so doing, the law also expressly preempts state and local “regulation[s]… concerning the energy efficiency, energy use, or water use” set for these same covered appliances. In short, the federal government sets energy efficiency standards for furnaces, hot water heaters and HVAC systems; therefore, local governments generally may not. (There are some exceptions to EPCA preemption, including for standards set in state and local building codes, so long as they offer a range of compliance options. Berkeley’s 2019 Ordinance was not part of a building code.) To date, few cases parse EPCA’s preemption provisions relating to appliance energy standards (and the ones that do look at the building code exception).

In California Restaurant Association, a trade group (the “CRA”) representing members “interested in opening a new restaurant or in relocating a restaurant to a new building in Berkeley,” brought suit against the city. The plaintiffs made both federal and state law claims. (The state law claims can be summarized for our purposes as asserting that Berkeley should have followed the state building code amendment process and other state laws in enacting its natural gas restrictions; those claims were not decided by the District Court and are not relevant for purposes of this post.) The federal law claims asserted that EPCA preempted the Berkeley Ordinance because the Ordinance effectively prohibits the use of natural gas appliances and therefore “concern[s] the… energy use” of covered building appliances. EPCA defines “energy use” as “the quantity of energy directly consumed by a consumer product at point of use,” and “energy” as “electricity, or fossil fuels.” According to the CRA, the Berkeley Ordinance effectively requires appliances covered by EPCA to directly consume “zero” natural gas.

The District Court was not persuaded by the CRA’s preemption argument, calling it an “expansive interpretation of the EPCA… remarkable for its sweeping breadth.” Citing precedents that call for a narrow interpretation of statutory preemption language, the court rejects the notion that EPCA preempts local ordinances that do “not facially address any of those [energy conservation or energy use] standards, let alone mandate or require any particular use of a covered product.” The court further notes that a prohibition on natural gas infrastructure in new buildings “is clearly outside the preemption provision of the EPCA.”

While the decision is undeniably good news for the Berkeley Ordinance, it also offers guidance to the many other local governments around the country considering some sort of restriction on building natural gas use, particularly outside of a state or local building code. First, the District Court puts to rest a broad reading of EPCA preemption that would disallow local laws that (1) do not facially or directly set energy efficiency or energy use standards but that (2) “have some downstream impact on commercial appliances.” In a September 2020 brief, the city of Berkeley lists precedent state and local requirements that regulate equipment “covered” by EPCA that nevertheless are not preempted by EPCA. State safety regulations, for example, set emergency egress requirements for cold-storage units, even though freezers are regulated by EPCA. Similarly, some local requirements in California restrict new swimming pools as a drought mitigation measure; Berkeley notes that EPCA does not preempt these restrictions as impermissible energy efficiency standards for pool heaters. While local governments will still need to navigate state law limitations, yesterday’s decision suggests that they need not overthink EPCA preemption; policies that have some indirect impact on EPCA-covered appliances will not be held preempted on that basis alone.

Second, the District Court repeatedly reaffirms that states and local governments have powers expressly or impliedly delegated to them that EPCA preemption was not intended to displace. In particular, the District Court cites “a city’s exercise of its power to regulate building infrastructure to protect public health and safety,” a traditional exercise of the police power left to the states under the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The decision also notes the federal Natural Gas Act’s delegation of “all aspects relating to the direct consumption of gas” to the states. Noting that “wide swaths of the U.S. … lack natural gas access,” the District Court reasoned that “nothing in [EPCA] evinces legislative intent to require local jurisdictions to permit the extension of natural gas service.” This endorsement of express and traditional sources of local government authority should give local governments some comfort that their building decarbonization policies will not be preempted by EPCA by virtue of their “downstream impact on … appliances.”

It should be noted that California Restaurant Association has not been finally decided. In addition to potential appeals, Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers dismissed the state law claims without prejudice, meaning that plaintiffs may bring those claims in state court. And, of course, every local government is subject to unique state law limitations. Still, the decision is a win for local governments. Cities can take from this decision that EPCA does not – beyond its express terms – impinge on their health and safety authority (to the extent delegated by the state), and that “downstream” consequences of their local laws on appliance energy use will not, without more, doom these local laws to preemption under EPCA.

Amy Turner is the Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.