On September 22, 2022, the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and the Columbia Climate School co-hosted a Climate Week NYC webinar on “Siting Renewables in New York: Ambitious Climate Goals, a New Siting Process, and How It Is Going.” This blog post will summarize the highlights of the event, focusing on updates from Executive Director Houtan Moaveni of the New York State Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES), as well as recommendations from panelists on how to further improve the siting process.

Background

In 2019, New York State enacted a landmark climate law called the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). The CLCPA requires that 70% of the State’s electricity be generated by renewable energy by 2030 and that 100% be generated by zero carbon sources, including nuclear and renewables, by 2040. See N.Y. Pub. Serv. Law §§ 66-p(2)(a), (b). The CLCPA also requires that emissions be reduced 85% from 1990 levels by 2050. N.Y. Envtl. Conserv. Law § 75-0107(1)(b). The CLCPA will require siting and developing a very large number of major renewable energy projects at an unprecedented pace throughout New York State.

However, at the time the CLCPA was enacted, the process for siting major renewable energy facilities, then governed by Article 10 of the Public Service Law, was too slow for the state to meet its goals. From 2011 to April 2020, when the Legislature finally created the new process described below, only six renewable energy projects had made it through the Article 10 process, and only one project had actually begun construction.

On April 3, 2020, to help the State achieve its mandates under the CLCPA, the Legislature enacted the Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act. Among other things, the law created a new Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES) to conduct a “coordinated and timely review” of all major renewable energy projects in the State to “meet the state’s renewable energy goals while ensuring the protection of the environment” and other considerations. See N.Y. Exec. Law § 94-c(1). Under the new law, ORES must make a decision on issuing a siting permit within one year of determining that an application is complete (or six months for projects proposed to be located on brownfields). Id. § 94-c(5)(f).

ORES Executive Director Houtan Moaveni’s Update

To kick off the event, ORES Executive Director Houtan Moaveni dialed in to provide an update on the agency’s progress implementing the new siting process. First, Moaveni provided some figures, including the following:

- To date, ORES has received 16 complete applications and issued seven final siting permits.

- So far, ORES has met all statutory deadlines and, for six out of seven of the approved projects, ORES issued its final decisions in “around six months,” well within the one-year deadline.

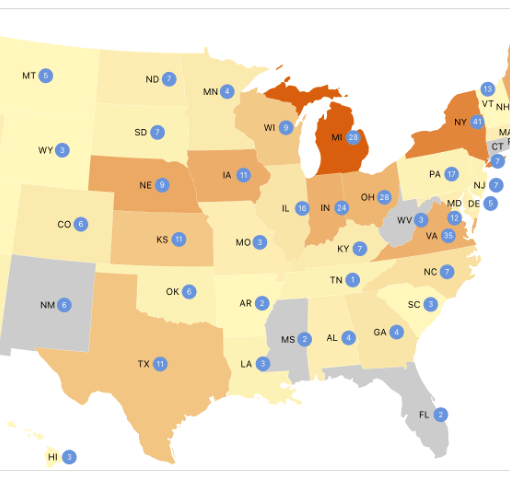

- In total, there are 74 major renewable energy facilities at various stages of progress in the application pipeline before ORES, which add up to roughly 11 gigawatts (GW) of capacity.

Moaveni stressed that while the quantity of applications and the speed of review are very important, the “quality” of the environmental impact assessment is “equally important.” He noted that, for all seven of the approved projects, ORES “conducted a detailed [environmental] review” and invited those viewing the webinar to review the dockets of individual projects here.

Second, when asked what distinguishes the new siting process from the Article 10 process that preceded it, Moaveni explained that there are “three cornerstones” of the new siting process, namely: (1) a mandatory pre-application process that requires applicants to consult with state agencies, host municipalities, and communities “to identify at the earliest point in the project planning and development process” the principal environmental and cultural resources impacts as well as important project- and site-specific issues of local concern; (2) a comprehensive application that includes 25 exhibits tailored to major renewable energy facilities, which “sets forth specific design goals and methodologies for analyzing potential significant adverse impacts [common to] these types of facilities”; and (3) uniform standards and conditions that “put applicants on notice” of the standards and conditions designed to address potential adverse impacts typically associated with “particular classes and categories of major renewable energy facilities.” Moaveni explained that these three cornerstones are intended to “inform facility design at the earliest possible stage,” to “avoid major siting impacts in the first instance before an application is submitted,” and to provide greater certainty to applicants.

Third, when asked whether he has any tips for participants in the siting process, Moaveni responded that: (1) “applicants should approach [ORES] early and often,” noting that “the earlier an applicant communicates with [ORES] staff, the greater the chance of eliminating any major issues for a proposed facility”; (2) applicants should seek to build local support for their projects, including by “establish[ing] a good working relationship with host communities and develop[ing] and maintain[ing] direct communication with local officials”; and (3) local governments and host communities should stay involved throughout the process.

Fourth, when asked whether ORES is positioned to help the State meet the CLCPA goals, which will require increasing renewable energy’s share of electricity from 27% to 70% by 2030, Moaveni responded that he is confident that ORES will achieve its mandate for two reasons: (1) because ORES has established an efficient “one-stop” process for scaling up renewable energy facilities that provides “increased certainty and predictability” while allowing consideration of pertinent social and environmental factors and providing transparency to local communities; and (2) because ORES has built a team of subject matter experts to implement the permitting process and established operational workflows with sister agencies to work together in a coordinate fashion to review proposed facilities.

Panel Suggestions on Further Improvements to the Siting Process in New York

Following the update from Executive Director Moaveni, there was a panel discussion among four experts: (a) Anne Reynolds of the Alliance for Clean Energy New York (ACE NY); (b) Noah Shaw of Foley Hoag LLP; (c) Cullen Howe of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC); and (d) Audrey Friedrichsen of Scenic Hudson.

The panelists were asked what is working about the new siting process and what could be improved. In response to the first question, the panelists generally agreed that the new siting process, which imposes clear deadlines on applicants and agency staff and sets out uniform standards and conditions, is a tremendous improvement over the previous process. In response to the second question, the panelists offered several suggestions on how to further improve the siting process. This section will focus on the latter.

a. Anne Reynolds (ACE NY)

Anne Reynolds, Executive Director of ACE NY, a membership-based organization whose members include renewable energy developers and other private companies, as well as environmental advocacy groups, offered three suggestions for improvement: (1) reducing the number of deficiency letters that applicants receive; (2) not requiring system reliability impact studies prior to submission of an application; and (3) implementing the provisions of the Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act that require DEC to establish a cohesive program for compensatory mitigation.

First, Reynolds argued that ORES should strive to issue one deficiency letter for each project rather than a series of deficiency letters. She explained, by way of background, that “[o]ne of the frustrations under Article 10 was that an application would be submitted, the response would be a deficiency letter, the applicant would answer the deficiency letter, and they would get another deficiency letter on a different topic.” She explained that this issue has not been fully resolved under the new process, adding that “[w]e really want to get to a place where every application just gets one deficiency letter with everything that the office wants.”

Second, Reynolds pointed out that, for an application to be deemed complete by ORES, the applicant currently needs to obtain a completed system reliability impact study (SRIS) from the independent system operator (ISO) that manages the power grid. See 19 N.Y.C.R.R. § 900-2.22(b). Reynolds argued that this type of study is “not relevant” to siting and should not be required as part of the siting process. For background, the purpose of a system reliability impact study is to evaluate the extent to which connecting a new source of energy to the grid will affect the reliability of the transmission system. Reynolds explained that such studies are ostensibly required as part of the siting process to “make sure the projects are mature,” but argued that this is not a sufficient basis to justify such a requirement when there is a “huge backlog” of such studies at the ISO.

Third, Reynolds explained that the Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act, the same law that created ORES and the new siting process, required DEC to set up a mitigation fund for impacts to endangered and threatened species. See N.Y. Envtl. Conserv. Law § 11-0535-c. She argued that DEC has not done so in the way the statute requires. Reynolds explained that the statute envisioned that “DEC would develop…projects to protect endangered and threatened species” and that “developers would contribute to [a] fund” to support such projects. Currently, however, if the State determines that a project has an impact that needs to be mitigated, DEC will instruct applicants to go out and find a project themselves. When applicants present a potential project to DEC for approval, DEC will reply along the lines of, “Nope, not good enough, how about something else?” In effect, Reynolds explained, the parties “go through a very iterative process to figure out what that project will be,” which is “extremely frustrating to developers.” Reynolds argued that this is “not efficient” and not what the statute requires. Reynolds further argued that if DEC identified the projects itself, as the statute requires, “the projects would be more impactful and cohesive [as] part of an overall wildlife management and protection program.”

b. Noah Shaw (Foley Hoag LLP)

Noah Shaw, a partner at Foley Hoag LLP, who serves as lead permitting counsel for several projects in front of ORES, offered three suggestions for improvement, all focused on communications, namely: (1) that ORES issue written guidance; (2) that the other agencies ORES relies upon be provided with adequate resources to assist ORES in a timely manner; and (3) that ORES staff and applicants communicate more consistently with one another throughout the siting process.

First, Shaw suggested that ORES should develop written “strategic guidance” for applicants. He explained that many permitting agencies have detailed guidance regarding how to interact with the agency in addition to their regulatory construct. He further explained that applicants who are not familiar with New York and ORES practices, informal and otherwise, often lack certainty in this respect, especially during the pre-application process.

Second, Shaw spoke about inter-agency communications and the need to ensure that other state agencies involved in the ORES consultation process have adequate resources to respond to requests from ORES in a timely manner. He pointed out that those agencies may have limited resources and competing priorities. He argued that we need to “make sure that DEC and DPS and Parks and everybody else actually have the ability to [act] in a timely way to support ORES so that ORES can move as quickly as it needs to.”

Third, Shaw argued that there needs to be more communication between ORES staff and applicants before and after the application is filed. He explained that “[t]here are lots of instances where a question may be begged by something in the application materials and literally with a five-minute phone call, it could be…figured out on day 5 of that 60-day period as opposed to all piling up and being…listed in some big document that comes out 60 days later.” He further argued that there need not be a “cone of silence for two months and then the big reveal about all the things that need to happen.” Shaw argued that having more consistent and constructive communications throughout the pre-application process would lead to “less work for staff and a more efficient, faster process.”

c. Cullen Howe (NRDC)

Cullen Howe, a Senior Attorney with NRDC’s Climate & Clean Energy program, offered two suggestions for improving the siting process, namely: (1) ensuring adequate staffing of ORES; and (2) increasing public acceptance of projects through education and outreach.

First, Howe explained that ORES initially had so few staff that he was concerned they would not be able to process the applications. While ORES appears to have sufficient staff for now, Howe believes ORES will still need to grow as the number of applications increases.

Second, Howe argued that, while he believes the State has done a good job of getting the policy right in Executive Law § 94-c, securing public acceptance of the projects is going to be a “harder problem to solve.” He noted that the State “can’t regulate” public acceptance and instead needs to do outreach and education, among other things.

d. Audrey Friedrichsen (Scenic Hudson)

Audrey Friedrichsen, a senior attorney at the environmental nonprofit Scenic Hudson, also offered two ideas for improving the new siting process, namely: (1) increasing public acceptance by incorporating local concerns into project design at an early stage and by coordinating agricultural policy and renewable energy policy and; and (2) providing a mechanism to address cumulative impacts to communities where there are multiple projects.

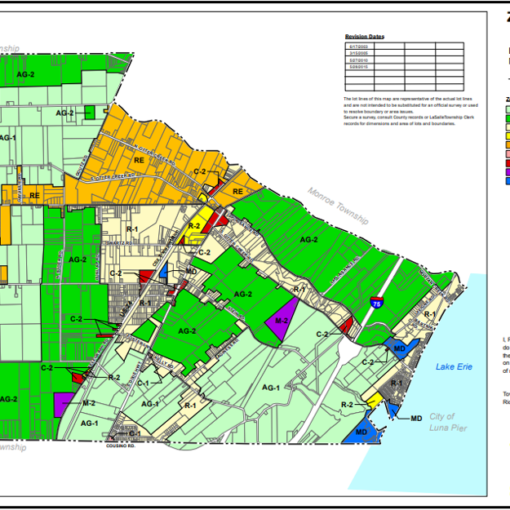

First, Friedrichsen argued that public acceptance of projects could be improved by more effectively incorporating concerns raised by stakeholders into project design and by more closely coordinating agricultural policy and renewable energy policy. Friedrichsen argued that, while the new siting process helpfully requires developers to meet with host communities early in the process, more could be done to incorporate the concerns raised in those meetings into project design. She further explained that many objections to renewable energy are based on perceived impacts to agricultural soils, farming, and the farm-based economy. Friedrichsen argued that more coordination between agricultural policy and renewable energy policy is needed during the siting process. She added, however, that the State deserves “a lot of credit” for having “brought together many stakeholders” on these issues in other forums, including the Agricultural Technical Working Group and Farmland Protection Working Group.

Second, Friedrichsen noted that New York’s siting process does not contemplate cumulative impacts on a specific area or community and raised the question of whether there should be an opportunity, either in the Executive Law § 94-c process or adjacent processes, to consider such impacts. Friedrichsen explained that, in certain communities, there are as many as three large-scale projects being proposed, and the residents are wondering “why us?” The answer, she explained, is usually that transmission is available, that the land values are right, or that there are landowners willing to site projects on their land. Nonetheless, Friedrichsen argued that there should be a mechanism to consider cumulative impacts, perhaps as part of the annual solicitation process of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). She suggested that, as NYSERDA considers its next portfolio of annual awards, it might consider whether there is “a particular community that is going to be seeing a lot of projects.”

Matthew Eisenson is a Senior Fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, where he leads the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative (RELDI).