By Dena Adler

The Trump Administration is losing on climate in the courts. More than two and a half years into the Trump Administration, no climate change-related regulatory rollback brought before the courts has yet survived legal challenge. Nevertheless, climate change is one arena where the Trump Administration’s rollbacks have been both visible and real. In total, the Sabin Center’s U.S. Climate Deregulation Tracker identifies a total of 94 actions taken by the executive branch in 2017 and 2018 to undermine and reverse climate protections.

But despite the Trump Administration setting a high-water mark for climate change deregulation, a new Sabin Center working paper, “U.S. Climate Litigation in the Age of Trump: Year Two” finds that due to vigilant litigation, the courts have largely constrained extralegal rollbacks and other attempts by the Trump Administration to undermine climate protections by overreaching executive authority, violating statutory requirements for environmental review, or flouting administrative law—at least thus far. (An executive summary of the paper is also available.) This paper updates a report on climate change litigation during the first year of the Trump Administration.

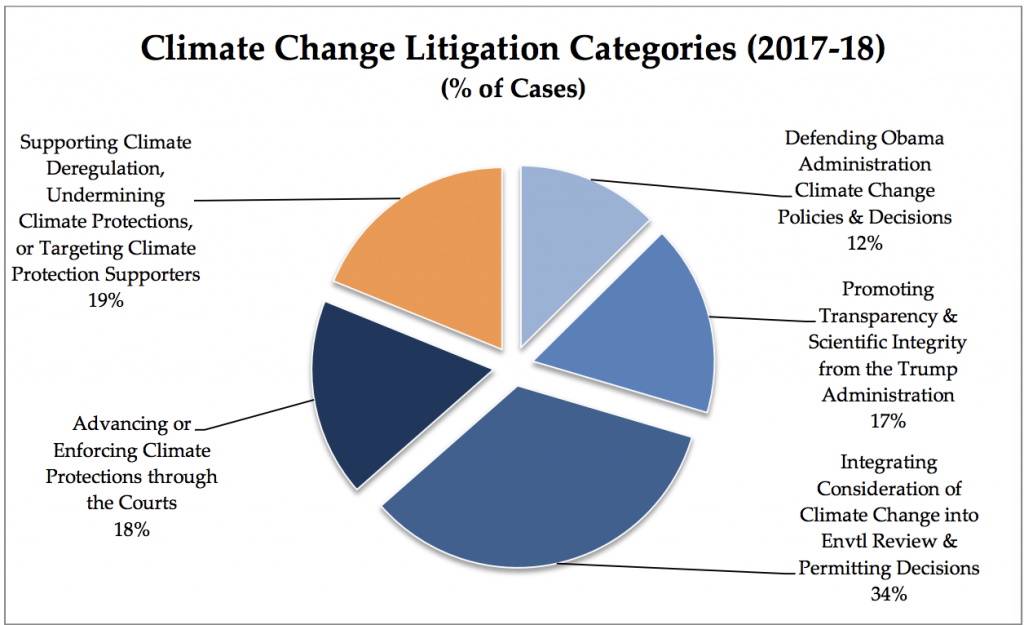

The “Year Two” report seeks to provide a landscape level view of how litigation is shaping climate change law and policy during the first two years of the Trump Administration. To this end, it categorizes and reviews dozens of climate change cases filed during 2017 and 2018 to shed light on how litigation is counterbalancing—and at times complementing—the Trump Administration’s efforts to undermine climate change protections. The analysis reviews 159 climate change cases, (defined as cases that raise climate change as an issue of fact or law), from 2017 and 2018 and pertaining to federal climate change policy. The paper sorts cases into five categories:

- Defending Obama Administration Climate Change Policies & Decisions;

- Demanding Transparency & Scientific Integrity from the Trump Administration;

- Integrating Consideration of Climate Change into Environmental Review & Permitting;

- Advancing or Enforcing Additional Climate Protections through the Courts; and

- Deregulating Climate Change, Undermining Climate Protections, or Targeting Climate Protection Supporters.

The first four categories are “pro” climate protection cases—if their plaintiffs or petitioners are successful they will uphold or advance climate change protections. The fifth category contains “con” cases—if their filing party or parties are successful, these cases will undermine climate protections or support climate policy deregulation. 129 of the reviewed cases were “pro” climate protection and 30 were “con.” To understand how federal climate change litigation is shaping national climate policy in the absence of federal leadership, the paper looks across and within these litigation categories to further examine: 1) who are the litigants, 2) what laws are they utilizing, and 3) how these cases have progressed thus far.

Key Report Findings:

- Lawsuits Advancing and Upholding Climate Protections Exceeded Those Opposing Climate Protections: The pro cases outweighed the con cases roughly 4:1 (81% to 19%).

- Direct Defense of Obama Administration Climate Policies Is Supplemented by a Wide Range of Other Lawsuits Supporting Climate Protections: Twenty of the 129 pro climate cases (16%) concerned “Defending Obama Administration Climate Change Policies & Decisions.” The other 109 pro cases supported climate protections through a variety of ways, including by increasing transparency around scientific misinformation and external stakeholder influence on government policies, upholding requirements to consider climate change impacts during environmental review and permitting, and seeking to compel additional or enforce existing climate protections.

- About a Fifth of Cases Sought to Undermine Climate Protections, But Fewer of These Cases Were Filed in 2018 Than 2017: Roughly one-fifth (19%) of reviewed cases sought to advance climate change deregulation, undermine climate protections, or attack supporters of climate protections. The number of these cases declined in 2018—only seven of the thirty cases in this category were filed in 2018.

- NGOs, Sub-National Governments, and Industry Actors Were Far and Away the Most Frequent Plaintiffs and Petitioners: Pro cases brought by NGOs represent more than half (99/159 cases or 52%) of the reviewed climate change litigation. Industry actors, (primarily private companies and trade groups), brought 16% of total cases and 70% of con cases.

- Thus Far, the Courts Have Not Upheld Any Attempts by the Trump Administration to Delay or Roll Back Regulatory Climate Protections: In 2017-2018, a dozen cases were filed that raised climate change as an issue of fact or law and concerned delay or suspension of climate-related rules. These cases have largely been struck down, voluntarily dismissed, or are still pending a final decision. Early decisions are building a body of precedent that clarifies limitations on the executive branch’s ability to destabilize duly promulgated regulations and to act without regard to proper procedure.

- Courts Have Halted Trump Administration Policies to Promote Fossil Fuel Extraction on Public Lands and in Public Waters for Inadequate Environmental Review and Executive Overreach: For example, recent court decisions have found that the Trump Administration violated requirements of environmental review in its attempt to reverse a moratorium for coal leasing on federal lands and acted beyond its statutory authority when it reversed the Obama Administration’s drilling ban on leasing in parts of the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Though yesterday the Ninth Circuit dismissed a case concerning an outdated Keystone XL Pipeline permit as moot in light of the issuance of a new presidential permit for the pipeline, that merely shifts the battle to litigation over the new permit. That dismissal does not undermine the legal logic of a lower court decision that halted construction of the pipeline prior to further environmental review.

To learn more, read the full report and executive summary.