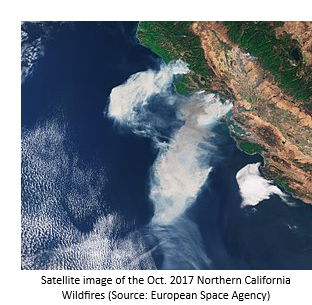

On October 9, 2017, the Tubbs Fire ripped through Sonoma County, California, destroying nearly 5,000 homes and killing 22 people. It was the most destructive wildfire in California’s history and the largest urban conflagration in the United States since the 1906 San Francisco earthquake fires. And it was only one of approximately 250 wildfires that sparked that same night in Northern California, causing a total of 44 fatalities and more than $9.4 billion in economic damages.

Now, nine months later, the process of reconstruction has begun. Some of the first homes have gone up on burned lots. Many of these lots are located in the “wildland-urban interface” – rural, forested areas on the outskirts of cities that are much more prone to wildfires. Commenters have questioned the prudency of rebuilding in these areas in light of existing fire hazard and predictions of how the warming climate will fuel more frequent and severe wildfires in the western United States. But there are social and economic factors which are driving reconstruction despite the risk – specifically, the emotional attachment of many property owners to the place they call “home” and the fact that property values in the areas remain extremely high (with some lots listed at over $1,000,000).

The availability of insurance is a critical factor for rebuilding. But many areas prone to wildfire are becoming too risky to insure. As noted in a 2017 report from the California Department of Insurance, premiums and wildfire surcharges have increased significantly in the wildland-urban interface, and several major insurers have stopped writing new policies and renewing plans in areas with high wildfire risk. As insurers begin to account for climate change in their wildfire risk models, they will likely become even less willing to issue and renew policies in these areas.

At this time, insurance is still available to property owners who are rebuilding their homes in the aftermath of the fires. This may be due, in large part, to a California law which prohibits insurance companies from cancelling a policy while a primary residence is being reconstructed after a covered disaster, and requires them to renew the policy at least once following a total loss caused by a disaster (Cal. INS § 675.1). The law provides short-term protection for property owners affected by the fires, but it does not guarantee that insurance will be available in the long run. Most homeowners’ insurance policies are written for a term of only 12 months, and there are no laws in California which prohibit an insurer from refusing to renew a homeowner’s policy (apart from the one exception noted above). The bottom line is that thousands of homes may be reconstructed due to the short-term availability of insurance, only to become uninsurable in the near future.

When private insurance becomes unavailable, there is still a fall back option: a state-sponsored program called the California FAIR plan. This program is already considered a “last resort” insurance option due to high premiums and coverage limits. As more property owners in high risk areas enroll in the plan, state regulators will likely need to increase rates to reflect risk exposure and reduce coverage limits to keep the program actuarily sound (as required by Cal INS § 10100.2). Ultimately, relying on the California FAIR plan as the primary insurer of homes in high risk areas may prove a losing proposition for the state – and recognizing this, the California Department of Insurance’s 2017 report outlines different legal approaches for maintaining private coverage in these areas, which include:

- Prohibiting insurance companies from cancelling or non-renewing a policy that has been in effect for a certain time period unless a strict rescission standard is met.

- Requiring that insurance companies obtain approval from the state insurance commissioner before they can materially reduce the volume of policies in a given area.

- Requiring insurance companies to provide mitigation discounts and continued coverage to homeowners who make investments in hardening their home.

All three approaches would require legislative action from the state of California.

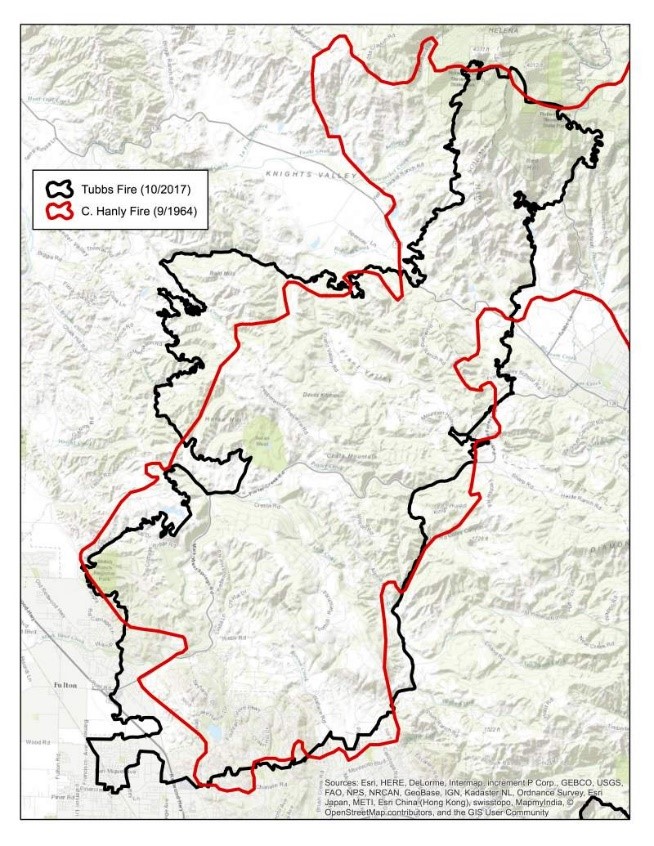

The problem with these types of approaches is that they do not address the underlying problem – that in some areas, wildfire risk may become so high that it does not make fiscal sense to construct and insure a home. Consider the region affected by the Tubbs Fire in Sonoma County. As illustrated on the map below, the Tubbs Fire followed almost exactly the same path as the 1964 Hanly Fire, which occurred under very similar circumstances: extremely hot, dry winds caused the fire to move rapidly westward. With two similar fires just 50 years apart, one might surmise that the risk of annual fire in this particular corridor is approximately 2% and that risk may grow due to factors such as climate change and the expansion of electrical infrastructure.

To put this into perspective: if an insurance company’s models determined that an area did in fact have a 2% annual risk of fire, then the company would need to charge a premium of at least 2% of the total policy coverage (e.g., $20,000 per year for a $1,000,000 home) and that doesn’t account for other risks, such as earthquakes or flooding. If annual wildfire risk were to increase to 5% or 10%, the premiums would soon become unaffordable.

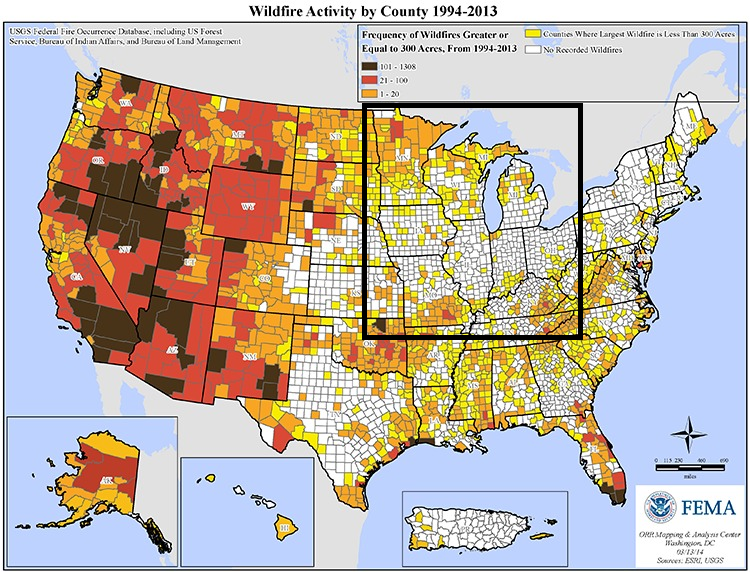

The Tubbs/Hanley corridor is not unique. Wildfire risk is prevalent across large swaths of the Western U.S., and research shows that the severity and frequency of western wildfires is increasing and will likely continue to increase as the climate warms.

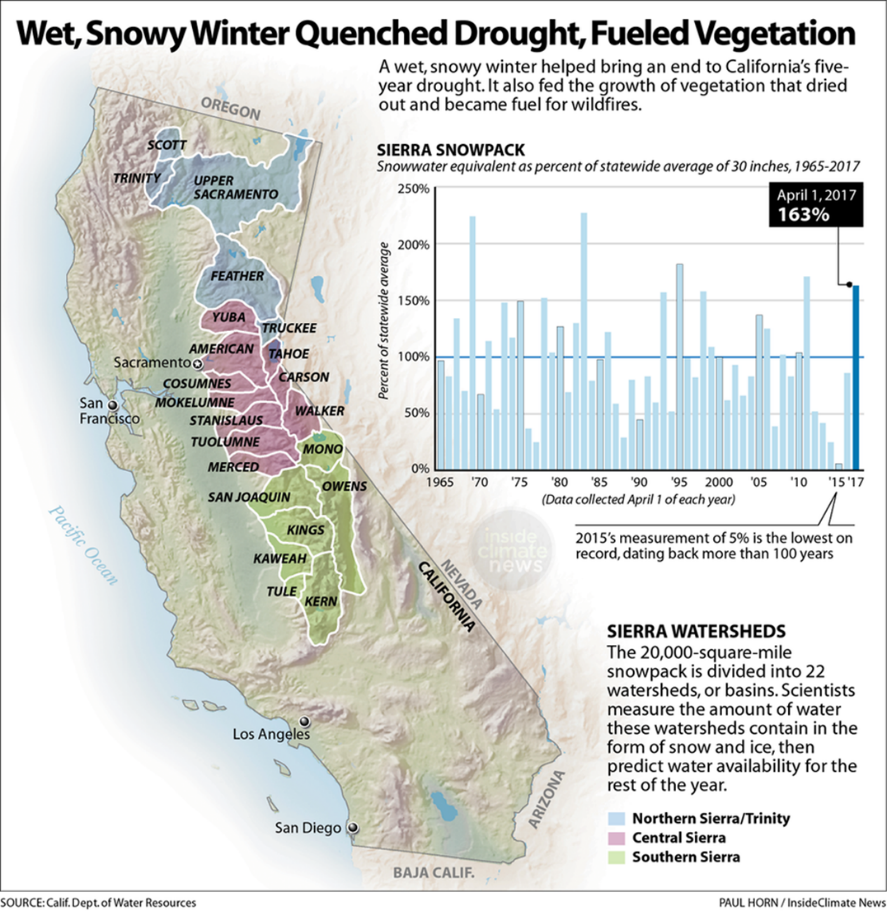

Climate change likely contributed to the severity of the Northern California wildfires in October. There are three specific ways in which climate change may have played a role. First, there was an unusually wet winter, which lead to the rapid growth of vegetation (fuel for the fire).

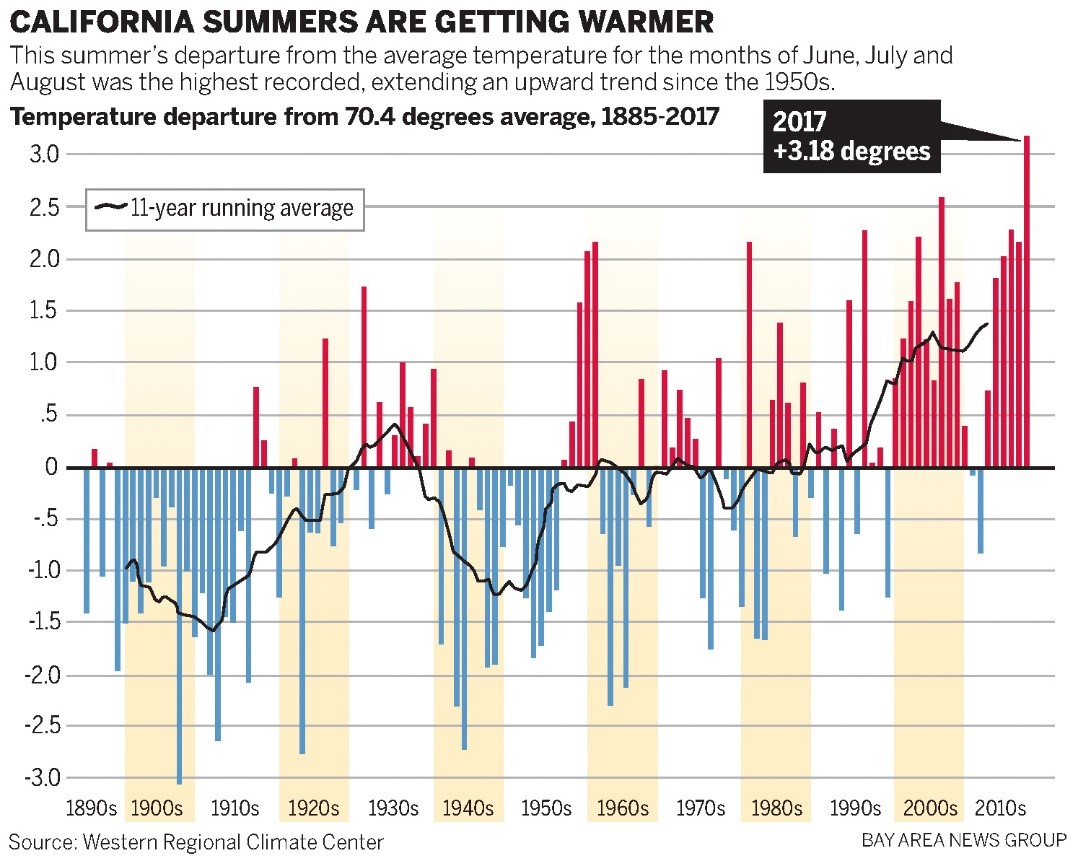

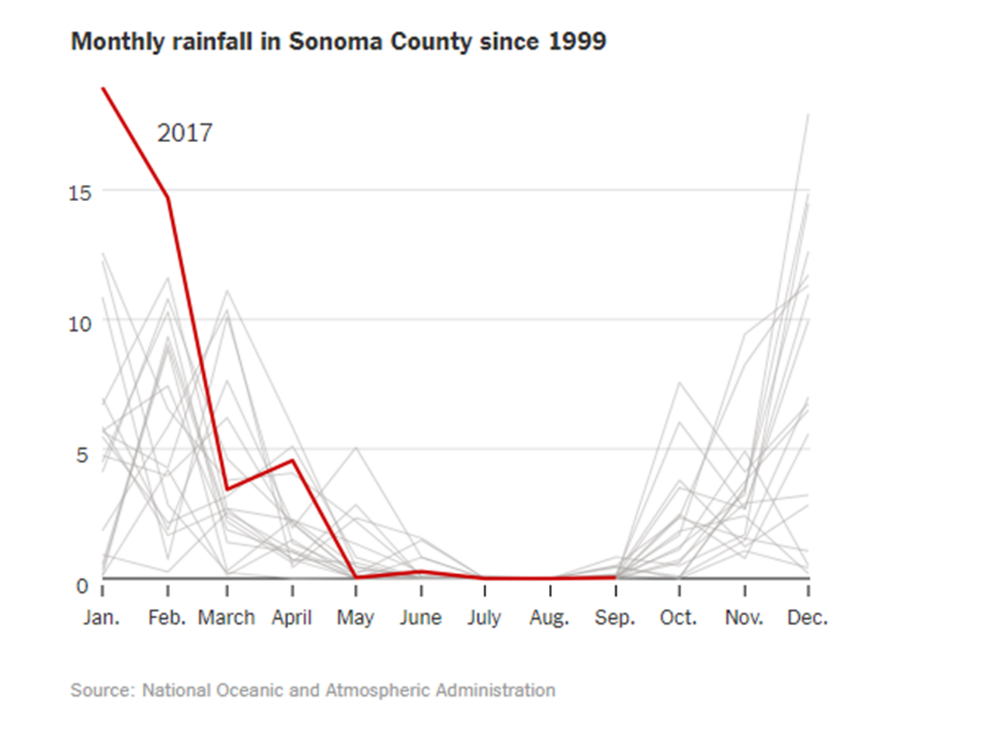

Second, there was an unusually long, hot and dry summer, which dried out all of that vegetation. As depicted below on the chart below, this is part of a long-term trend.

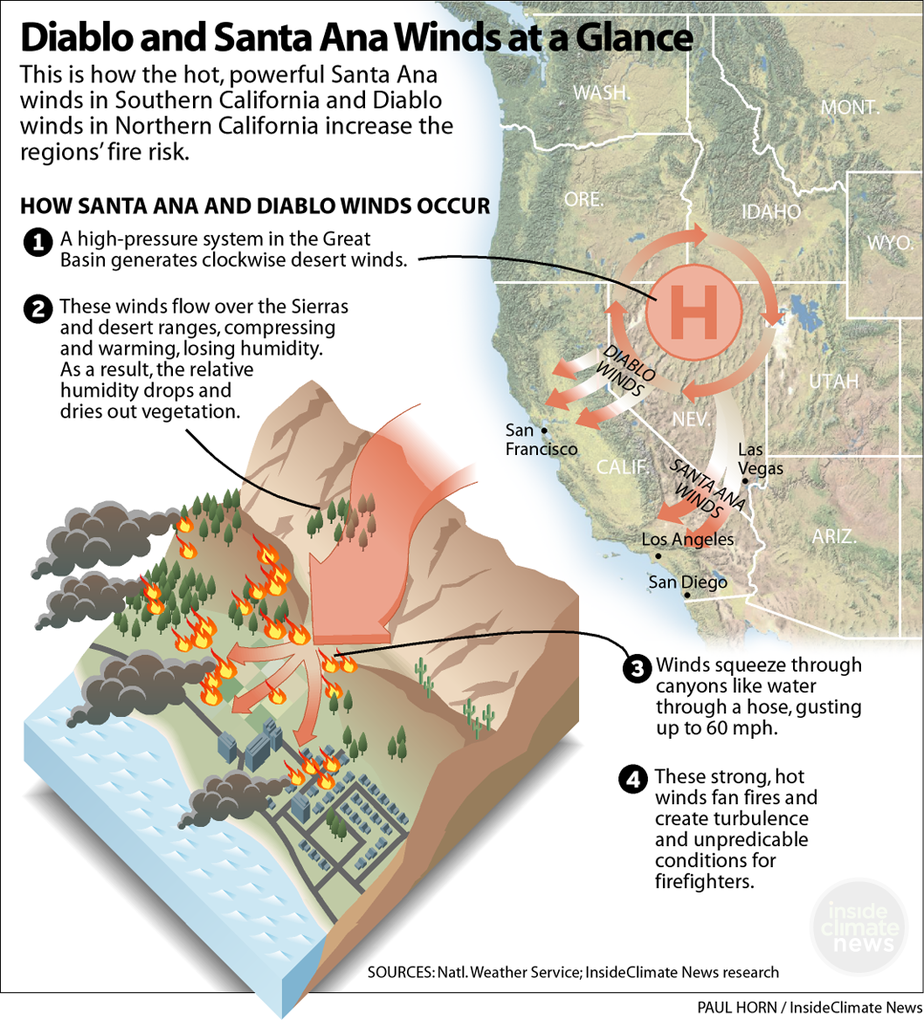

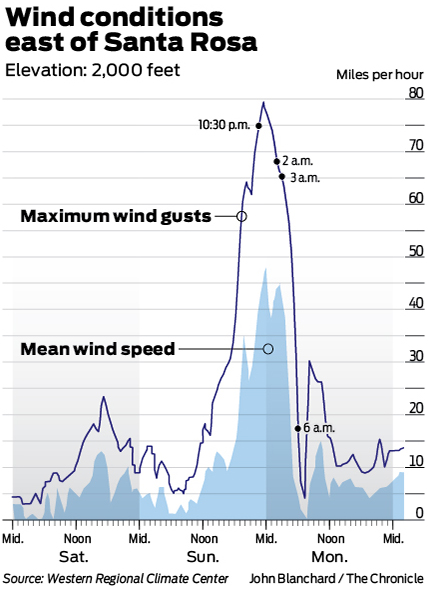

Sonoma County – which was hit hardest by the fires – experienced a particularly sharp decline in rainfall between winter and summer (the red line on the chart below shows how 2017 compares to previous years). Third and finally, there were unusually strong “Diablo” winds the night of the fire which caused its rapid spread. Wind gusts reached nearly 80 mph shortly after the fire ignited. Research has linked increases in the frequency and severity of these winds to climate change.

Third and finally, there were unusually strong “Diablo” winds the night of the fire which caused its rapid spread. Wind gusts reached nearly 80 mph shortly after the fire ignited. Research has linked increases in the frequency and severity of these winds to climate change.

To make fire-prone areas insurable (and livable), we need to address the underlying fire risk. Certainly, climate change is a significant contributor to wildfire risk and we need to quickly reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate that contribution. But there are also more local actions that can be done to reduce wildfire risk and make communities and natural landscapes more resilient in the context of a changing climate. These include:

- Putting electrical infrastructure underground so that it does not spark fires (PG&E’s power lines have already been identified as the cause of many of the Northern California wildfires)

- Vegetation management programs aimed at reducing fuels as well as restoring forest health, removing non-native species, and creating favorable conditions for the propagation of fire-adapted species such as oak trees and redwoods.

- Building fire-hardened homes that are less likely to ignite in the event of a wildfire.

- Building fire breaks to prevent the spread of fires.

In addition to fire prevention and risk mitigation measures, it will also likely be necessary to provide additional resources for fighting fires. The limitations of existing resources were evident the night of the Tubbs fire: there was no effort to halt the initial spread of the fire because many fire crews had been sent to fires that had broken out earlier in the evening, and those that remained were busy getting people out of harm’s way.

All of these measures will be expensive, which raises the question of who should foot the bill. It makes sense for those living in the wildland urban interface to pay additional fees to invest in fire prevention and preparedness. Such fees have been unpopular in the past, but residents may be more willing to pay if it will help them maintain insurance coverage. There are also some costs that could be distributed more broadly among segments of society – for example, fire prevention on public lands, and the cost of undergrounding electric transmission infrastructure that serves urban populations. And if fossil fuel companies are found liable for damages associated with climate change, then local governments may be able to recover some funding for fire-related adaptation measures from those companies. But ultimately, if people want to continue to live in fire-prone areas, they should be prepared to pay more to address wildfire risk (whether through insurance premiums, fire fees, or direct costs associated with hardening homes and removing vegetation).

Going forward, state regulators and local governments should consider how they might align policy goals pertaining to fire risk reduction and insurance availability. For example, regulators could work with insurance companies to create a program whereby insurance is available to homeowners in fire-prone areas if certain criteria are met (e.g., the house is constructed to meet fire-hardening standards, there is a defensible space on the property, and the homeowner pays a fire fee for vegetation management). The 2017 report from the California Department of Insurance touches on some policy and legislative approaches, but there is ample room for more discussion and policy innovation in this field.