By Romany M. Webb

On Tuesday, January 28, House Democrats published a draft of the so-called “CLEAN Future Act” which aims to “achieve a 100 percent clean economy by not later than 2050.” The Act’s authors describe it as a “comprehensive” plan for achieving “net zero greenhouse gas pollution, while also . . . revamp[ing] the U.S. economy and uplift[ing] the middle class.” An important component of the plan is stricter regulation of methane, which is both a highly potent greenhouse gas and a valuable source of energy that could be captured and used, resulting in economic and environmental benefits. Despite this, however, any attempt to strengthen methane regulation is likely to be staunchly opposed by the Trump administration.

Last year, the administration rescinded key provisions of the Methane Waste Prevention Rule, which was adopted by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) under President Obama, and required oil and gas producers on federal lands to capture methane. Three other Obama-era methane rules adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) – one targeting the oil and gas industry and the other two applying to landfills – are currently under review and expected to be substantially weakened. Many lawmakers are starting to push back, however. Along with the CLEAN Future Act, lawmakers are currently considering five other bills, aimed at preventing the Trump administration rolling-back existing methane regulations and/or requiring further regulatory action. To inform the ongoing debate about those bills, this blog reviews the history and current status of methane regulation in the U.S.

Why Regulate on Methane Emissions?

A highly potent greenhouse gas, methane is the second largest contributor to climate change, after carbon dioxide. While emitted in smaller quantities than carbon dioxide, methane is a much more potent warming agent, trapping 87 times more heat in the earth’s atmosphere in the first 20 years after it is released (on a pound-for-pound basis). Methane also contributes to the formation of other heat-trapping greenhouse gases. For example, global methane emissions are estimated to have caused two-thirds of the observed rise in tropospheric ozone which, as well as trapping heat in the lower atmosphere, also contributes to ground-level smog, which can cause various respiratory and other health problems.

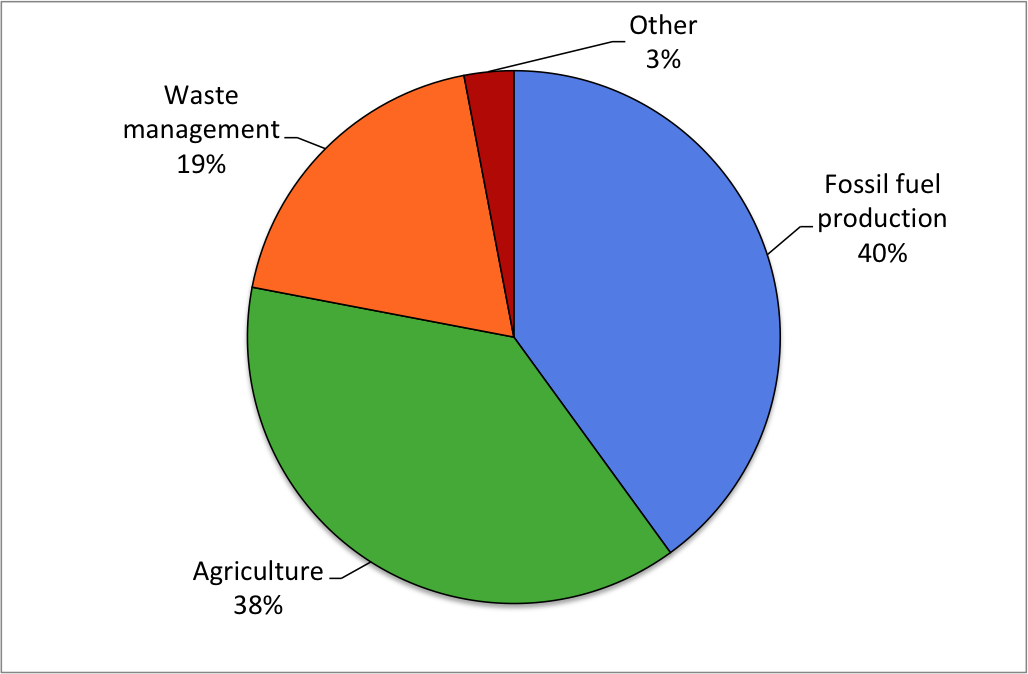

Despite these negative impacts, methane emissions have historically been subject to little regulation at the federal level, perhaps because of the economic and political importance of the key emitters. The fossil fuel industry is currently the largest source of methane in the U.S., accounting for 40 percent of national emissions in 2017. Nearly two-thirds of industry emissions (64 percent) occurred during the production and transportation of natural gas, primarily due to accidental leakage and intentional venting of gas, which is 95 to 99 percent methane. Leaks and venting also occur during coal mining and oil production, as both resources are often co-located with natural gas, resulting in further methane emissions.

After fossil fuel production, agriculture is the next largest source of methane in the U.S., accounting for 38 percent of national emissions in 2017. Most agricultural emissions are attributable to the raising of livestock as methane is released by cattle and other ruminant animals during digestion and from the breakdown animal waste. The breakdown of human waste, in landfills and wastewater treatment plants, is the third primary source of methane in the U.S., accounting for 19 percent of emissions in 2017.

Both geologic methane (i.e., released during fossil fuel production) and biological methane (i.e., from agriculture and waste management) can be used as a source of energy to produce heat or generate electricity. This would have economic benefits for emitters, who could sell the methane to third parties or use it themselves, thus reducing their energy costs. However, emitters are often reluctant to invest in gas capture systems, including due to their high upfront cost and uncertainty regarding the payback period. Regulation is, therefore, needed to encourage or require the capture and use of methane.

Methane Regulation During the Obama Administration

Federal efforts to address methane emissions did not begin, in earnest, until 2014, when the Obama Administration unveiled its Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions. While far from comprehensive, the strategy proposed an initial set of regulatory measures to control methane emissions from oil and gas production, coal mining, and landfills. The strategy also outlined several voluntary emissions reductions programs, targeting the above sectors and agriculture. Notably, the strategy did not provide for regulation of agricultural methane emissions, presumably because Congress has prohibited such regulation in each annual appropriations act passed since 2009. (See section 437 of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act 2020 for an example.)

In accordance with the strategy, in 2016, EPA adopted three sets of methane-related regulations under section 111 of the Clean Air Act (CAA) (42 U.S.C. § 7411). Briefly, section 111 of the CAA provides for EPA regulation of stationary sources that “cause[], or contribute[] significantly to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” Under section 111(b), EPA must establish technology-based standards, known as new source performance standards (NSPS), for new stationary sources of such pollution. Once NSPS are issued with respect to a particular type of stationary source, EPA must (with limited exceptions) adopt emissions guidelines to regulate existing sources of the same type under section 111(d).

Acting pursuant to section 111 of the CAA, EPA adopted regulations to control methane emissions from:

- Landfills: EPA adopted NSPS for municipal solid waste landfills constructed or modified after July 17, 2014, and emissions guidelines for landfills existing prior to that date. Both the NSPS and emissions guidelines require large landfills (i.e., with a design capacity of 2.5 million cubic tons (by mass) and 2.5 million cubic meters (by volume)) to install gas collection systems once their emissions of non-methane organic compounds reach 35 metric tons per year. EPA estimated that this will reduce annual methane emissions by approximately 368,000 short tons by 2025 because landfill gas typically consists of approximately 50 percent methane.

- Oil and gas production: EPA also adopted NSPS for certain oil and gas facilities constructed or modified after September 18, 2015. The NSPS impose restrictions on gas venting and flaring at new oil wells and require enhanced leak detection and repair at new gas wells, gathering and processing facilities, and transmission compressor stations. According to EPA, this will reduce methane emissions by 510,000 short tons in 2025 and could deliver even larger emissions reductions in future years, as more facilities become subject to the NSPS.

Shortly after finalizing the oil and gas NSPS, EPA issued an information collection request to oil and gas producers, seeking data needed to develop emissions guidelines for existing facilities (i.e., constructed or modified before September 18, 2015). At the time, EPA indicated that it was fully committed to addressing emissions from existing facilities but, as discussed below, the agency’s position changed markedly following President Trump’s inauguration.

Also in 2016 BLM adopted the Methane Waste Prevention Rule to limit methane emissions from oil and gas production on public lands. The Rule was adopted under the Mineral Leasing Act (30 U.S.C. § 181 et seq.) which requires BLM to ensure that persons leasing public land “use all reasonable precautions to prevent waste of oil or gas developed in the land.” Concluding that venting, flaring, and leaks result in gas wastage, BLM established a new capture target, requiring 95 to 98 percent of the associated gas produced from oil wells to be captured (i.e., rather than vented or flared), and imposed strict leak detection and repair requirements on oil and gas facilities (among other things). Unlike the EPA regulations, the requirements apply to all facilities on public lands, regardless of age.

Deregulation Under President Trump

President Trump’s election halted, and may ultimately reverse, federal action to address methane emissions. Shortly after taking office, the President signed Executive Order 13783 directing federal agencies to review and, if appropriate, revise all existing regulations “that potentially burden the development or use of domestic energy resources, with particular attention to oil [and] gas.” Pursuant to the Order, BLM and EPA commenced reviews of the Methane Waste Prevention Rule and oil and gas NSPS, respectively. EPA also commenced a review of the landfill NSPS and emissions guidelines.

BLM completed its review of the Methane Waste Prevention Rule in September 2018. At that time, BLM rescinded key provisions of the rule, including the gas capture targets, and leak detection and repair requirements. (For more information about the rescission, see my previous blog here.) The rescission was immediately challenged by the states of California and New Mexico, as well as several environmental groups, in the Northern District of California. The litigation was ongoing at the time of writing.

Also ongoing was EPA’s review of its methane regulations. While EPA had sought to stay each regulation pending review, those stays have either expired or been successfully challenged in court, meaning that the regulations are currently in effect. EPA has, however, proposed to substantially weaken or rescind the oil and gas NSPS. As previously reported, due to the regulatory structure created by the CAA, rescinding the NSPS would not only eliminate the methane controls currently imposed on new oil and gas facilities, but also obviate the need for EPA to adopt new controls for existing facilities. That appears to be the Trump administration’s ultimate goal. Former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt implied as much when, in March 2017, he withdrew the request for information needed to develop emissions guidelines for existing facilities.

Congressional Reaction to Deregulation

The Trump administration’s plan to deregulate methane emissions has been met with mixed reactions on Capitol Hill. There initially appeared to be some support for deregulation in the House which, in February 2017, passed a resolution to repeal BLM’s Methane Waste Prevention Rule. The Senate, however, voted against the resolution. Two other bills – one (H.R.637) intended to “void” EPA’s oil and gas NSPS and the second (H.R.7231) to limit application thereof – also failed in the 115th Congress. The second bill was reintroduced (as H.R.1391) this session, but has so far languished in committee, and is considered unlikely to pass. There now appears to be more support, at least in the House, for maintaining or even strengthening methane regulation.

This Congressional session five bills have been introduced which, if enacted, would codify existing methane regulations and/or force additional regulatory action. One example is H.R.4143, the so-called Super Pollutants Act, which would codify the oil and gas NSPS adopted by EPA in 2016 and require the agency to develop emissions guidelines for existing oil and gas facilities within 2 years. Notably however, under the Super Pollutants Act, those guidelines would only take effect if industry did not voluntarily reduce emissions. Industry would be afforded less flexibility under the draft CLEAN Future Act which, as well as codifying the oil and gas NSPS, provides for the adoption of emissions guidelines to take effect immediately. The CLEAN Future Act does, however, provide for the establishment of new programs to assist industry to reduce emissions.

While the CLEAN Future Act does not currently have bipartisan support, several of the other bills introduced this session (including H.R.4143) do. Whether they will pass remains to be seen, but their introduction is significant in itself, and suggests that methane regulation may soon be a federal priority again.