By Bernard E. Harcourt

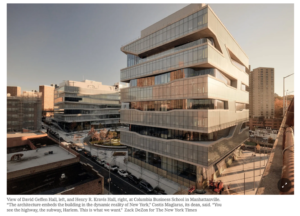

Columbia University has built a new campus for its business school whose architecture will transform capitalism. In Harlem, at the new sprawling Manhattanville campus, prize-winning architects will transform Columbia Business School into a social justice bastion. The New York Times headline (above) says it all.

Columbia president Lee Bollinger captures the transformative nature of the architecture and its ability to ring in a new era of socially conscious capitalism. The Columbia Business School will soon have, as its neighbor and thinking partner, the recently established Climate School, which will be designed by the Genoa-based Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

“The forces at work in the world are necessarily causing a rethinking of the foundations of the economic system we’ve had,” Bollinger tells the New York Times. “Climate change, issues of social justice and what globalization means for societies — all of these are raising profound questions about the nature of what the future can be.”

No more corner offices for professors, the new architecture will weave students and faculty on alternating floors so that they have no choice but to mingle in the meandering stairwells—the “network stairs”—lounges and cafes that will offer views, the New York Times writes, of the “brick tenements and public housing towers — in the process reminding people of the messy world beyond.”

The former dean of the Columbia Business School, Glenn Hubbard—who, you may recall, had a starring role in the documentary Inside Job about the financial meltdown of 2008—praises the new architecture: “We are trying to come up with a framework that can be more about flourishing, not just profit.” According to the New York Times, Hubbard was the person who “saw the need to break free from fealty to the unregulated free market economy that over decades has led to extraordinary wealth concentration. The idea that business should focus only on making money, attributed to the economist Milton Friedman, ‘was a simple and direct idea that took over business, banking, even corporate law,’ Hubbard explained.” No more. With these new buildings and this new architecture, we enter an end of history beyond the free market.

The architecture also makes room for lots of business school centers dedicated to nonprofits, climate change, and social justice for formerly incarcerated people. “The Columbia-Harlem center coaches local producers of food, gifts and cosmetics,” the New York Times reports. “Several products that were introduced with the help of the program are sold in a ground-floor public cafe and in nearby Whole Foods stores.”

To some, the architecture is awe inspiring and exudes socially-conscious capitalism.

Probably not, though, for anyone who has read Manfredo Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia, or spent time with Reinhold Martin’s book Utopia’s Ghost, or learned from Felicity Scott’s Architecture or Techno-Utopia, or came across Tony Vidler’s “Diagrams of Utopia.”

No, the utopia polemics in architectural theory that emerged in the wake of Tafuri’s 1969 article “For a Critique of Architectural Ideology”—which Tafuri reworked and enlarged into Architecture and Utopia—cast a dark shadow over these dreams, aspirations, and hopes in Harlem.

The Utopia Polemics

Tafuri himself would have laughed at all this ideological banter of “doing good while making money,” of a new business school ethic that is “more about flourishing, not just profit.” “Today,” Tafuri wrote, “the principle task of ideological criticism is to do away with impotent and ineffectual myths, which so often serve as illusions that permit the survival of anachronistic ‘hopes in design.’”[1] Yes, Tafuri would have made quick work of these Manhattanville illusions.

How on earth could these prize-winning architects, who are so deeply enmeshed in capitalist modes of production, ever honestly believe that they would be engaged in a utopian transformative project when they are building space for the future of capitalism? How could any commercial architect working within the constraints of the financial and corporate world possibly hope that their design could resist or transform capitalism? In 2023?

Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia blew open these questions, tracing the long history of architecture’s failures at breathing life into utopian dreams. Published in 1973, Architecture and Utopia came at a moment of a certain post-utopianism, and contributed to it. The 1970’s, Felicity Scott reminds us, “marked a watershed and a distinctly postutopian turn. As disenchantment grew with the capacity of recent strategies to effect structural change—from megastructures, domes, and “environmental design” to inflatables and student insurrections—critical and/or utopian vocations for architecture began to seem not only idealistic but […] even impossibly foreclosed.”[2]

Tafuri unveiled architectural illusions through a searing ideology critique. He offered, in Scott’s words, a “despondent reading of architecture’s prospects under capitalism” and a “recognition that avant-garde strategies of resistance and negation had come increasingly to serve the very machinations of an ever more totalizing capitalism.”[3] In demonstrating capitalism’s uncanny ability to overcome resistance and new social forms, his work bears resemblance to Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello’s later book, The New Spirit of Capitalism.[4]

Another Dialectic

In the ensuing utopia polemics, a lot turned on the dialectical relationship or constant struggle between the ideal and the real, between the architectural ambition and the realized project. That tension infused much of the debate.

Tony Vidler associated this “divide between ideal and real,” between “the real and the copy” in Charles Sanders Peirce’s words, between “the schematic and the real,” with the diagram, as opposed to the architectural sketch.[5] The diagram, Vidler proposed, could serve as an instrument of utopia because, in a way, it was not real. It was schematic. It was a model. Vidler points us to the schematic cross-section of Charles Fourier’s design for his phalanstère.[6] “The diagram may be seen as an instrument of and for utopia,” Vidler writes—and vice versa. “All utopias are, of necessity,” Vidler adds, “diagrammatic.”[7]

Might that then give us hope for a way forward, out of the abyss?

It is easy to come out of these readings with some pessimism about architecture and its utopian potential, though that itself may be a necessary precursor to a more chastened view of utopia. It could be that Tafuri’s specter needs to haunt our discussions of utopia. Perhaps it is necessary to constantly recall the dialectic, or failure, in order to guard against illusions or not get carried away with them. This is perhaps reflected in Reinhold Martin’s essay, “Utopia, Again,” which concludes on a cautiously uplifting note: “Utopia’s ghost stands ready—if we are willing—to re-enter the historical stage at a time when nothing less will do.”[8]

In fact, many of the final paragraphs in the tradition of the utopia polemics betray a glimmer of hope. Tony Vidler concludes his meditations on “Diagrams of Utopia” with a similar twist. “The diagram in this context can act to galvanize the discourse only if both political form and architectural form are entered into its equation.”[9] Only, to be sure; but it can, nevertheless. Reinhold Martin concludes his first chapter of Utopia’s Ghost, “Territory: From the Inside Out,” with what he calls a “counterdiagram,” arguing for public housing, rather than affordable housing or sustainable housing, and in that act, risking utopia again. “The choice is whether or not to demand unambiguously public housing with all of its risks, responsibilities, and double binds,” Martin asks, “and thereby to ‘risk’ the dimly perceptible thought called Utopia again.”[10]

Felicity Scott’s book as well has a silver lining. In her words, it argues that

capitalism can be understood to resolve all contradictions only if we continue to regard the dialectic itself [the dualism of melancholy versus uncritical techno-optimism] as the sole mechanism of historical transformation. If we do not, other (positive) prospects arise within that passage of postmodernization, and it is these prospects, and the new modes of social and political subjectivity they subtend, that this book aims to trace within architecture.[11]

All of this suggests that the key question for architectural theory, post-Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia, may be whether the more operative divide, rather than of the ideal and the real, is instead that of disappointment and cautious reconstruction. Perhaps the key moment of the utopia polemics is the dialectic of disillusionment and reconsidered utopia. This could be thought of as the architectural form of Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”

In that dialectic, the path forward may be to eschew Big Architecture and turn instead to more grounded cooperative projects—to cooperation. Within architecture, one direction might be cooperative projects such as the Rural Studio in Alabama or Xavi Laida Aguirre’s initiatives like stock-a-studio or ‘The Digital Now: Architecture and Intersectionality’. Or to public housing as a political right, as Martin suggests in his essay, Utopia, Again. This might represent, in his words, “architecture’s utopian project, scaled back from the horizon of revolution to what prison abolitionists and others call ‘non-reformist reform’: housing as a political right, articulated in the superstructure by the arts and sciences of the built environment in a realistic fashion that, under current conditions, cannot help but appear unreal.”[12]

Space and heterotopias

The topic of “architecture and utopia” brings us back, more so than other sessions, to the spatial dimension of utopia and heterotopias, back from our long historical journey through the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries that produced the tectonic shift in the concept of utopia “from space into time,” as Ernst Bloch wrote—from the spatial realm of geography and architecture to the temporal realm of history. History remains a key dimension, of course; capitalist development demands it. But space once again dominates.

One lesson of being so grounded in buildings, projects, construction, and the architecture of utopia is that, for the rest of us outside the architectural domain, confronted with that dialectic, we too see how entangled we are within systems that sap our projects of their utopian potential. Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia presents a deep challenge to the non-architects among us, who are just as embedded in capitalist modes of production. What makes us think that we could escape those attachments any more than the architectural utopian could? The tentacular hold of extractive capitalism in architecture unveils its equally hegemonic, dominating role in law, in higher education, throughout the American university, in book publishing, etc. Does Big Law differ in any relevant way from Big Architecture? How do we, in a law school, in a political science department, at a press, resist or escape the fealty to the wealthy donors and the exploitation of capital?

These are some of the questions we will explore with our panel of brilliant, critical architectural theorists, Xavi Laida Aguirre, Reinhold Martin, Felicity Scott, and Anthony Vidler.

Welcome to Utopia 13/13!

Notes

[1] Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, trans. Barbara Luigia La Penta (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979), at 182.

[2] Felicity Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics After Modernism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), at 3.

[3] Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics After Modernism, at 8.

[4] Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, Le Nouvel esprit de capitalisme (Paris: Gallimard, 1999).

[5] Anthony Vidler, “Diagrams of Utopia,” Daidalos 74 (2000): 6-13, at 10, 6, and 10.

[6] Vidler, “Diagrams of Utopia,” 7.

[7] Vidler, “Diagrams of Utopia,” 7.

[8] Reinhold Martin, “Utopia, Again,” essay for Utopia 13/13, April 16, 2023.

[9] Vidler, “Diagrams of Utopia,” 13.

[10] Reinhold Martin, Utopia’s Ghost: Architecture and Postmodernism, Again (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), at p. 26.

[11] Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics After Modernism, at 11.

[12] Martin, “Utopia, Again.”