Last week marked the one year anniversary of President Trump’s second inauguration, and of the Sabin Center’s Climate Backtracker. We launched the Backtracker on inauguration day, January 20, 2025, to record actions taken by the Trump-Vance Administration to scale back or wholly eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures. The tracker is linked to our database of climate change regulations, which documents the history of climate action in the U.S. since the start of the Obama Administration.

So far, President Trump’s second term reflects a doubling down on the anti-climate actions that we witnessed during his first term. In just his first year back in the White House, we’ve recorded 304 deregulatory actions, and counting. The Administration’s policy on climate has been characterized by efforts to advance President Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda, stymie what he terms the “Green New Scam,” and undo foundational elements of the United States’ climate policy.

Back in April, we wrote a blog post about the deregulatory actions taken in the first 100 days of President Trump’s term, where we offered four initial observations: (1) that the Trump Administration appears to be moving much quicker in his second term compared to his first, according to our data; (2) that the first 100 days brought numerous executive orders and announcements of sweeping deregulatory plans but few formal rulemaking activities; (3) that the Administration was issuing interim and direct final rules without notice and an opportunity to comment; and (4) that the Department of Energy (DOE) was the most active agency in climate deregulation. Nine months later, some of those still hold true and some have evolved as the Administration’s deregulatory agenda continues to unfold. For instance, while the Trump Administration has continued to make use of executive orders and memoranda, the rate at which they are issued has declined. On the other hand, we have seen a ramp up in the issuance of proposed and final rules, most of which propose major regulatory roll-backs. And DOE has continued to lead the agencies in deregulatory actions, though the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has advanced its deregulatory agenda considerably in recent months.

Based on entries in the Backtracker thus far, the five busiest agencies have been (1) DOE, with eighty-three recorded actions; (2) the White House, with fifty-eight recorded actions; (3) the Department of the Interior, with forty-eight recorded actions; (4) EPA, with forty-five recorded actions, and (5) the Department of Transportation, with twenty-six recorded actions. We consider deregulatory actions to include announcements of changes in policy, rulemaking and related activities, memoranda and guidelines for agency executives, and similar administrative actions that implicate deregulation in climate policy. Project-specific decisions or announcements are generally not included, unless they have nationwide implications.

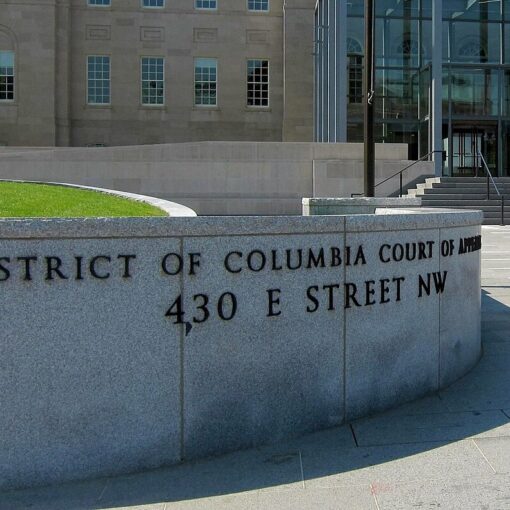

The Trump Administration has vastly expanded its use of executive orders, presidential memos, and proclamations from its first term to its second term. In the first year of his first term, President Trump issued thirteen such actions focused on climate policy; in the second term, he has issued fifty-eight in the first year—a nearly 350% increase. This reflects the Administration’s broader efforts to expand presidential power. Executive Orders were particularly prominent at the outset of President Trump’s second term—twenty were issued in the first 100 days—and have since slowed, with only ten more in the remainder of the first year. They are still outpacing the first term numbers, though: President Trump issued six Executive Orders related to climate law and policy in his first term. See Figure 1.

One particularly notable Presidential action this term was Executive Order 14192 (Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation), which required all Executive agencies and departments to identify at least 10 regulations to repeal for every new regulation promulgated. That Order has driven agencies to pursue a raft of deregulatory actions. Indeed, the White House announced in December that it had achieved a 129-to-1 deregulatory ratio, dramatically exceeding the 10-to-1 target.

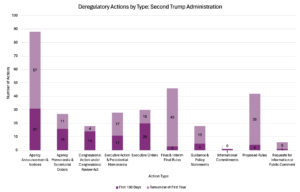

Figure 1: Deregulatory Actions by Type, First to Second Term. This graph shows the number of deregulatory actions taken by type in the first year of the First Trump Administration and the first year of the Second Trump Administration, as recorded in the Sabin Center’s Climate Deregulation Tracker and Climate Backtracker, respectively. We counted 75 total actions in the First Administration as of January 20th, 2018, and 304 in the Second Administration as of January 20th, 2026.

Figure 1: Deregulatory Actions by Type, First to Second Term. This graph shows the number of deregulatory actions taken by type in the first year of the First Trump Administration and the first year of the Second Trump Administration, as recorded in the Sabin Center’s Climate Deregulation Tracker and Climate Backtracker, respectively. We counted 75 total actions in the First Administration as of January 20th, 2018, and 304 in the Second Administration as of January 20th, 2026.

As we noted in our 100 days blog post, the second Trump Administration came out of the gate quickly with announcements, notices, and executive actions that indicated lofty plans for major regulatory changes. But after 100 days, the Administration had only issued three rules and four proposed rules—less than 8% of all actions. Now, the Executive branch has started to catch up with the promised formal rulemaking: proposed rules, interim rules, final rules, and other rulemaking activities now make up nearly a third (31%) of the total actions in the Backtracker.

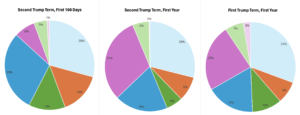

Figure 2: These graphs show the distribution of type of agency action during the first 100 days of the Second Trump Administration, the first year of the Second Trump Administration overall, and the first year of the First Trump Administration. Types of actions were grouped as appears in the key to the right.

Over the course of the first year of the second Trump administration, the distribution across action types has settled into a similar pattern as the first term. As noted previously, the first 100 days of the second term were dominated by White House action (29% of all Executive branch actions) and minimal deregulatory rulemaking activities (8%). But, now that a full year has passed, the breakdown of second term actions is comparable to what we saw in President Trump’s first term. This may reflect a reversion to a “business-as-usual” approach to deregulation—albeit at a much higher output—as in the First Trump Administration.

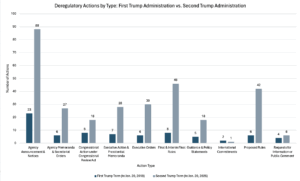

Figure 3: Deregulatory Action by Type, First 100 Days to Second Term Overall. This graph shows the number of deregulatory actions taken by type in the first 100 days of the Second Trump Administration and the remainder of the Second Trump Administration. There were 106 actions taken in the first 100 days, and 198 actions taken in the remainder of the Second Administration as of January 20th, 2026.

Figure 3: Deregulatory Action by Type, First 100 Days to Second Term Overall. This graph shows the number of deregulatory actions taken by type in the first 100 days of the Second Trump Administration and the remainder of the Second Trump Administration. There were 106 actions taken in the first 100 days, and 198 actions taken in the remainder of the Second Administration as of January 20th, 2026.

The Administration’s overall strategy is clearly intended to prop up the fossil fuel industry, while simultaneously making it harder to develop renewable energy resources, particularly solar and wind. Early on in his second term, President Trump issued several executive orders directing agencies to take action along these lines, including Executive Order 14154 (Unleashing American Energy); Executive Order 14156 (Declaring a National Energy Emergency); and Executive Order 14153 (Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential). In response, agencies have made permitting of wind and solar projects more challenging, reopened an Alaskan refuge for oil and gas development, and adopted procedures to fast-track permitting for fossil fuel projects. They have also sought to pause or terminate already permitted wind and solar projects and revive coal plants that were set to close.

In support of the crusade against renewable energy and championing of fossil fuels, the Administration is seeking to roll back or repeal environmental regulations that form the bedrock of US climate policy. For example, EPA has proposed to repeal its 2009 greenhouse gas endangerment finding, which enables it to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles and stationary sources. The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) rescinded its National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) implementing regulations and guidance on considering climate change impacts under NEPA. Individual agencies are following suit, modifying or rescinding their NEPA regulations (see, e.g., the Department of Transportation and the Interior Department). By removing CEQ’s uniform regulations and guidance and returning to an agency-led approach to NEPA, there is no longer a clear, government-wide mandate to consider climate change impacts under NEPA analysis. Several agencies have also adopted “categorical exclusions” to the requirements of NEPA, including the Interior and the Department of Homeland Security, some of which pertain to fossil fuel projects.

Consistent with these deregulatory actions of broader reach, agencies have also proposed to roll back specific greenhouse gas emissions standards, including the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards and EPA’s coal- and natural gas-fired power plant emissions standards.

On the international front, the Trump Administration has also taken notable steps to turn away from coordinated global efforts to address climate change. These include withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, withdrawing from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and blocking the International Maritime Organization’s “Net-Zero Framework,” which would impose a global carbon tax for greenhouse gas emissions from ships.

As expected, President Trump has made attacks on climate change policy a centerpiece of his second term. Deregulatory actions taken so far have been numerous and broad in scope. It still remains to be seen whether the Administration can effectively abandon certain key regulations; EPA’s repeal of the 2009 endangerment finding, for example, would surely be challenged in court. But if the first year is any indication of what’s to come over the next three years, there is still a long road ahead for climate action. The Climate Backtracker will continue to record the Trump Administration’s actions to ensure a clear understanding of the status of federal climate policy.