The Trump administration has undertaken a comprehensive effort to prevent the distribution of mandatory federal funding, including billions for climate programs. Attempts to cancel already-obligated federal funding awards have been among its most notable actions and have been met with a slew of lawsuits by aggrieved grantees, states, and other parties harmed by the cancellations. Over the last few months, the Sabin Center has covered developments in the litigation related to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) efforts to terminate nearly $27 billion in grants made through the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), a spending program created by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to finance various greenhouse gas reduction activities. As detailed in previous blog posts, plaintiffs have raised a variety of arguments but have faced headwinds in court, particularly with respect to an ongoing dispute over the proper federal court to hear the cases.

Despite their notoriety, grant cancellations are not the only means by which the administration has attempted to interfere with federal funding. Agencies have also taken various actions to delay disbursement, change program requirements, or otherwise withhold funds that it is obligated by statute to make available. In these instances, there may be another avenue by which to challenge the federal government’s unlawful interference with funding: the Impoundment Control Act (ICA). Enacted in 1974, the ICA prohibits the executive branch from withholding congressional appropriations, except under certain limited circumstances.

This blog post provides background on the ICA, summarizes three recent ICA decisions that pertain to climate programs, and discusses how the ICA might factor into the future resolution of the Trump administration’s withholding or rescission of climate funding.

Background on the Impoundment Control Act

The ICA prohibits the President or executive agencies from impounding (i.e. withholding) mandatory appropriations without the consent of Congress. Congress passed the ICA in 1974 “in response to attempts by [President Nixon’s] executive branch to refuse to spend congressionally appropriated funds.” The rationale for the law is simple: the Constitution vests in Congress the “power of the purse.” Under separation of powers principles, the executive cannot unilaterally refuse to spend Congress’s appropriations, simply because it disagrees with the policy that the funding advances. Nixon’s refusal to spend appropriations across various federal programs—the impetus behind the ICA’s enactment—highlighted how branches of government can collide, and the ICA establishes a clear and public procedure for the Executive to withhold funds.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent agency within the legislative branch, has a special role in enforcing the ICA. The GAO is led by the Comptroller General, who is appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Comptroller General serves a 15-year term, and can only be removed from office through impeachment or a joint resolution of Congress in prescribed circumstances.

Under 2 U.S.C. § 686, the Comptroller General has the authority to make reports to Congress when the President has failed to comply with the requirements of the ICA. Under 2 U.S.C. § 687, the Comptroller General also has the authority to sue the executive for impounding appropriations in violation of the ICA. In a recent decision in Global Health Council v. Trump, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals explained that the Comptroller General is the “enforcer of the [ICA’s] statutory scheme” and the D.C. District Court is “expressly empowered” to issue orders to make the impounded funds available upon a successful showing of an ICA violation. As explained more fully below, it is not clear whether parties other than the Comptroller General can bring enforcement actions under the ICA.

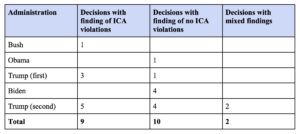

The GAO’s website lists 21 decisions issued by the Comptroller General under the ICA since 2006. Those decisions break down by administration and outcome as follows:

What happens when the GAO finds violations of the ICA? Legally, not a whole lot. Violations of the ICA do not come with penalties—administrative, criminal, or otherwise. As noted above, the Comptroller General of the GAO can sue to compel disbursements of funds impounded in violation of the ICA, but this is not common. In the half-century since the ICA’s enactment, the Comptroller General has brought one legal challenge. That 1975 lawsuit was mooted when the challenged program’s funding was revived. Still, even where lawsuits are not brought, publicizing ICA investigations and violations can help get impounded funds released. For example, in 2020, the Comptroller General determined that the Office of Management and Budget had unlawfully impounded appropriations for Ukraine security assistance. The administration eventually released the funds in response to pressure brought on by the added scrutiny. The same could prove true with the DOT and FEMA violations.

Recent Comptroller General Decisions on Climate-Related Impoundments

In the climate context, the GAO recently investigated and issued decisions for three possible ICA violations. These decision were made pursuant to a request by the House and Senate Budget Committees sent on March 31, 2025 to investigate several Trump directives that paused federal funding, including the executive order “Unleashing American Energy.”

In May 2025, the GAO issued a decision that the Department of Transportation (DOT) violated the ICA by withholding funds appropriated for the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Program, a federal formula program created through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that provides funding to states to deploy electric vehicle charging stations. The GAO found that DOT delayed the program’s implementation in violation of the ICA by imposing requirements on the program that are not contemplated by the IIJA. The Office of Management and Budget called the GAO decision “wrong and legally indefensible,” and told DOT to disregard the report. However, a group of states brought non-ICA claims against the federal government to get, among other things, their apportioned NEVI funds released for obligation. On June 24, 2025, the District Court for the Western District of Washington preliminarily enjoined the Trump administration from freezing NEVI funds for fourteen states. The federal government has not appealed the order.

In September 2025, the GAO determined that the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) violated the ICA by “improperly withholding, delaying, or effectively precluding the obligation or expenditure of budget authority for the following programs: Emergency Food and Shelter Program (EFSP), Shelter and Services Program (SSP), and Next Generation Warning System Grants Program (NGWS).”

Finally, in August, the GAO found that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had not violated the ICA when, pursuant to certain executive orders (including “Unleashing American Energy”) and internal memoranda, the agency temporarily paused obligations and expenditures for its Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Because USDA is empowered to exercise a significant amount of discretion over the implementation of EQIP, GAO determined USDA permissibly paused obligations and expenditures of EQIP funds based on the executive orders and memoranda.

ICA Implications on the Future Resolution of Impounded Funds

What happens next? As noted above, the GAO decisions are merely reports to Congress, without binding effect or associated penalties. While the Comptroller General of the GAO can sue to enforce the ICA, they have historically shied away from doing so. This administration’s extremely broad interpretation of executive authority to impound funds could very well be seen as justifying a different approach this time. If the Comptroller General does sue, the Trump administration will almost certainly respond by challenging the constitutional validity of the ICA. Leading up to and in his second term, President Trump has repeatedly claimed that the ICA is an unconstitutional constraint on executive authority.

At least one other factor will bear on whether the GAO sues to enforce the ICA or even continues to investigate the Trump administration’s actions: the current Comptroller General, Gene Dodaro (appointed by President Obama), will end his 15-year term in late December. This means that an administration that has consistently tested the boundaries of, and violated, the separation of powers doctrine now gets to choose its top watchdog. The laws dictating the Comptroller General’s appointment and removal ensures some degree of independence. A 10-person bipartisan commission—composed of the Speaker of the House, the President pro tempore of the Senate, the majority and minority leaders of the House and Senate, and the chairmen and ranking minority members of the Senate’s Committee on Governmental Affairs and House Committee on Government Operations—is required to compile a list of candidates for the Comptroller General. President Trump must select an appointee from that list. And, as noted above, President Trump cannot fire the Comptroller General at will. Removal requires congressional action.

Still, the GAO’s general restraint in suing to enforce the ICA, and the impending leadership change, calls into question the effectiveness of relying on the GAO to prevent the administration’s unlawful impoundment of congressional appropriations. As an alternative to GAO action, private parties could seek to enforce the ICA themselves, but will likely face major hurdles in establishing their right to sue.

Several federal courts have held that the ICA does not allow a private cause of action. Most recently, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals confirmed this in Global Health Council v. Trump. In its decision to vacate the district court’s preliminary injunction, the court held that the ICA’s provision authorizing the Comptroller General to bring enforcement actions precludes private parties from suing to enforce the ICA under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). This is consistent with a decision from the Court of Claims in Rogers v. United States, which was affirmed by the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals.

Other federal courts leave the question open. For example, the Rhode Island District Court recently stated in New York v. Trump that it would not adopt “such a narrow view” that private parties cannot seek to enforce the ICA through the APA. It reasoned that the APA prohibits agencies from acting “not in accordance with law,” which applies to “any law” including the ICA (citing the Supreme Court’s decision in FCC v. Nextwave Personal Communications Inc.). Although the Supreme Court has only dealt with the ICA in passing, its recent grant of an emergency application in Dept. of State v. Aids Vaccine Advoc. Coalition, No. 25A269 (U.S. Sept. 26, 2025) suggests that a majority of Justices may view the ICA as only permitting the Comptroller General to bring enforcement suits to compel appropriated funds to be released. These types of interim orders are not conclusive on the merits, however. That being said, the cases that directly address the scope of the ICA’s enforcement strongly favor the interpretation that only the Comptroller General may bring enforcement suits.

Conclusion

GAO investigations, decisions, and enforcement actions can serve as important checks against executive impoundment of congressionally appropriated funds. However, getting funds successfully released depends on several variables, including whether the GAO initiates an investigation, whether Congress applies pressure, and who is able to bring enforcement actions under the ICA.

Ultimately, the Trump administration’s expansive view of executive control over spending revives the same constitutional tension that led Congress to enact the ICA in 1974. Whether and how the GAO and Congress reassert authority will shape the future of federal climate funding and the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches.