This post is the first of a new Climate Law Blog series, 100 Days of Trump 2.0, in which the Sabin Center offers reflections on the first hundred days of President Trump’s second term across a variety of climate-related topics. To read other posts from the series, which will roll out over the course of the next week, click here.

On January 20, 2025, Inauguration Day, the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law launched the Climate Backtracker. This resource records the second Trump administration’s efforts to scale back or wholly eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures and other forms of climate risk disclosure and management. As expected, the first hundred days of this administration have seen a flood of announcements, executive orders, and initial efforts at rulemaking, aiming to do just that.

The Climate Backtracker is the latest phase of our long-standing project to catalog the evolution of federal climate change regulation though shifting presidential administrations, including initial efforts during the Obama administration (followed in our Climate Action Plan Tracker, with data still available in our Climate Regulation Database); deregulatory efforts by the first Trump administration (captured in our Climate Deregulation Tracker); and re-regulatory actions during the Biden administration (recorded in our Climate Reregulation Tracker). Data collected across the four administrations are helpful to illuminate trends in federal climate change regulation over time but also to ensure that the public is made aware of the scope of action, whether good or bad, especially in the current political climate.

Although the Trump administration has proudly touted many of its headline deregulatory priorities—like those that align with President Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda—it has also taken actions which may be somewhat more subtle but have critical implications for the fight against climate change. It has, for example, issued an interim final rule eliminating the Council on Environmental Quality’s implementing regulations under the National Environmental Policy Act; invited the regulated community to seek broad exemptions from regulations limiting hazardous air pollutants; and tried to stop state and local governments from enforcing their own climate laws.

Here, we offer a few initial observations on the administration’s deregulatory agenda:

First, this administration is moving much more quickly than the first Trump administration. By this time in the first administration, we captured fifty-one actions to roll back climate regulations, including five executive orders and one presidential memorandum. In contrast, the second Trump administration hit the ominous milestone of a hundred climate deregulatory actions before President Trump even reached his hundredth day in office. As of today, the administration has produced 106 actions to weaken or eliminate climate regulation, including twenty executive orders, seven presidential memoranda, and two proclamations. That pace reflects not only President Trump’s penchant for issuing executive orders but also his more aggressive push to expand executive authority through presidential decrees. A hundred days into this administration, there are more actions in the Backtracker coming directly from the White House than from any federal agency.

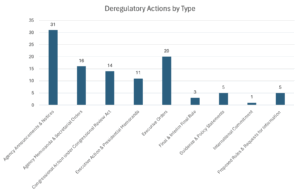

Second, although the second Trump administration has announced plans for major regulatory changes, it still has a long way to go to actually implement those changes. A breakdown of the deregulatory actions by type illustrates that the White House and agencies have been signaling big plans, for example, with many executive orders, agency announcements, and notices. But they are just getting started putting those plans into action, with only three rules and four proposed rules issued so far. It remains to be determined exactly how and when the administration will follow through on announcements like EPA’s “greatest day of deregulation our nation has seen,” the Department of Energy’s (DOE) plan to postpone energy efficiency standards across a range of appliance types, and the White House’s 10-to-1 rule for repealing existing regulations every time a new one is adopted. But statutes and the operation of administrative law require more than presidential say-so.

Third, as an end-run around the above, the administration is attempting to repeal at least some final rules without giving the public opportunity to comment. In an April 9, 2025 memorandum, President Trump directed agencies to fast-track repealing regulations that he argues impede economic growth and may be inconsistent with recent Supreme Court precedent on administrative law. The memorandum argues that “notice-and-comment proceedings are ‘unnecessary’ where repeal is required as a matter of law to ensure consistency with a ruling of the United States Supreme Court.” This claim runs counter to the long-standing provisions of the Administrative Procedure Act, where notice-and-comment is a default process required when agencies seek to issue new rules or repeal old ones. The process provides procedural safeguards to ensure that administrative rules are made in accordance with law, the public interest, and rational decision-making.

Agencies have already begun carrying out those orders. Prompted by a separate Executive Order titled “Maintaining Acceptable Water Pressure in Showerheads,” the DOE published a final rule repealing its definition of “showerhead” and asserted that it need not engage in public notice and comment because the Executive Order directed the agency to proceed without doing so. Similarly, the Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published a final rule repealing a 2023 regulation that addressed highway emissions, and suggested that “notice and an opportunity for public comment are unnecessary for this rulemaking because FHWA does not have legal discretion to allow the [greenhouse gas] measure to become effective.” These novel arguments and any similar ones the administration makes for silencing public input on its deregulatory agenda are all but certain to be challenged in court.

Fourth, DOE has been the quickest to implement the President’s agenda—DOE alone has produced twenty-three of the 106 actions recorded in the Backtracker so far—but EPA will likely catch up soon. Most of DOE’s work has been scaling back energy efficiency standards for appliances, including by delaying the standards’ effective date, excluding categories of products, and promising more similar actions to come. EPA, despite its outsized role in federal regulation that relates to climate change, has been slower to implement the Trump administration’s deregulatory directives than other agencies. But it has announced that it will be pursuing a massive deregulatory effort, taking on long-standing pieces of federal climate regulation like the 2009 Endangerment Finding, emissions standards for power plants, the mandatory Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, and many more. EPA’s slower pace may reflect its effort to more deliberately craft deregulatory actions on the primary contributors to greenhouse gases in the United States—namely power plants and motor vehicles, along with the oil and gas sector—to increase the likelihood they may survive legal challenges.

More is happening at other agencies too, which additional blog posts on this administration’s first 100 days will cover in more detail. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission has stopped defending its climate disclosure rules. Several agencies within the Department of Treasury have been withdrawing from international agreements relating to climate finance. And the Department of Interior is seeking to slash the time it spends on environmental reviews for fossil fuel projects down to a month or less.

This administration is moving fast to unwind federal climate regulation across the board. The foreshadowed deregulation to come will vastly expand on efforts already underway. But reviewing courts will not accept repeals that are premised solely on the President’s whims. Wanting to advance the administration’s agenda quickly does not excuse the agencies from taking public comment required by law. And regulatory decisions cannot be based on political factors at odds with the governing statutes. If the administration continues down this path, courts will stop much of what it aims to do.

As all these and more next steps unfold, the Sabin Center will continue tracking the Trump administration’s actions in the Backtracker.