Solar for All Implementation in 2025

Following his inauguration on January 20, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order directing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to freeze the $7 billion Solar for All (SfA) program created via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). SfA represents a massive investment in residential solar energy across the country. SfA awardees are to use grant funds to support “low-income and disadvantaged communities to deploy or benefit from zero-emissions technologies,” for example, by financing solar installations and battery storage for single- and multi-family households and community solar programs. Relying on publicly available information, this blog post examines the progress SfA awardees have made in establishing their offerings, and the risks they face from the Trump administration. The goal is to help local governments, community groups, and others that could benefit from SfA programs plan for what lies ahead.

Following his inauguration on January 20, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order directing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to freeze the $7 billion Solar for All (SfA) program created via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). SfA represents a massive investment in residential solar energy across the country. SfA awardees are to use grant funds to support “low-income and disadvantaged communities to deploy or benefit from zero-emissions technologies,” for example, by financing solar installations and battery storage for single- and multi-family households and community solar programs. Relying on publicly available information, this blog post examines the progress SfA awardees have made in establishing their offerings, and the risks they face from the Trump administration. The goal is to help local governments, community groups, and others that could benefit from SfA programs plan for what lies ahead.

The SfA Program under the Biden and Trump administrations

All of the funds Congress appropriated for SfA – $7 billion in total – were awarded by EPA during the Biden administration. Before President Biden left office, EPA entered into final, legally binding grant agreements with the 60 awardees. Under those agreements, the awardees—mostly states and some nonprofits—are required to provide grants and other financial assistance to households, local governments, developers, and others to support solar energy development. Awardees are also expected to provide technical assistance to help households and others overcome non-financial barriers to advancing solar projects and support workforce development.

These initiatives will deliver real benefits to communities all across the country. Installing solar energy and battery storage systems within communities can help to reduce local air pollution, combat climate change, improve the reliability of electricity services, and reduce costs (among many other benefits). SfA was designed to ensure that all Americans, including those in low-income and disadvantaged communities, can realize these benefits. Indeed, EPA has estimated that SfA “will enable over 900,000 households in low-income and disadvantaged communities to benefit from distributed solar energy.” The Trump administration doesn’t seem to care about that, however.

On his first day back in the White House, President Trump signed Executive Order 14154, entitled Unleashing American Energy, which directed federal agencies to “immediately pause the disbursement of funds appropriated through the [IRA] or the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (Public Law 117-58).” Shortly after that, SfA awardees reported that their grant accounts had been frozen, and that they were unable to access funds. This remained the case even after two separate federal courts issued temporary restraining orders and then preliminary injunctions directing federal agencies to unfreeze IRA funds. The situation apparently changed on February 26, 2025, when EPA stated that it had fully restored SfA grant funds. With funding restored, SfA grant awardees can continue developing and implementing their offerings uninterrupted – for now at least. As discussed further below, new EPA administrator Lee Zeldin has been highly critical of SfA, and there are concerns that the agency may attempt to terminate grants under the program and claw back funds, as it has attempted to do under other similar initiatives.

Implementation of SfA: Awardees Progress to Date

Planning Periods and Launch Dates

SfA is intended to be a multi-year initiative. SfA awardees have up to five years to deploy grant funds. Sabin Center research indicates that no SfA awardees have started dispersing funds to sub-awardees, but that is to be expected. The SfA program is structured such that awardees have up to one year to develop their offerings and begin dispersing. It appears that most, if not all, SfA awardees are using 2025 as a planning year and anticipate launching their offerings in mid-to-late 2025 or early 2026. For example, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, which received a $62,450,000 award from EPA, expects to launch its offerings in waves. Financial assistance for projects in multi-family housing may be available by the end of June 2025; single-family financial assistance may be available shortly after that; and technical assistance funding may be finalized by the end of 2025. As another example, Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy has indicated that it plans to use 2025 to design its offerings and engage with stakeholders. Pilot opportunities may be available in the summer of 2025, but the full rollout is not expected until January 2026. Rollouts for each awardee’s offerings will vary, but should occur no later than one year after they received their award.

The freezing of SfA funds in late January and February may have impacted some awardees’ planning processes. During the freeze, some awardees had to decide whether to delay hiring staff and planning activities or risk no reimbursement. Due to its relatively short duration, it’s possible that the funding freeze will not have a significant impact on the launch-timing of individual SfA offerings or the program’s long-term success. Much will depend on what happens in coming months.

The Trump administration’s stance on climate policy remains volatile and presents ongoing risks to the SfA program. EPA’s administrator, Lee Zeldin, has been on the attack for weeks now, making unsubstantiated allegations that EPA’s clean energy programs, like SfA, are rife with “waste, fraud, and abuse.” On March 19, 2025, EPA’s Office of Inspector General initiated an audit of SfA, presumably hoping to find evidence that would back up the administrator’s claims. While there is nothing to suggest awardees have done anything wrong, that may not matter to the Trump administration. As previously reported on this blog, EPA recently moved to terminate awards made under other clean energy programs and claw-back funds based on what a court described as “vague and unsubstantiated assertions of fraud,” without any “legal justification.” There is a real risk EPA will seek to do the same thing here. If that happens, implementation of the SfA program, and the benefits it is expected to provide, would be at real risk.

SfA Financial Offerings

SfA awardees are expected to use most of their grant funds from EPA to provide financial assistance to local governments, households, and others seeking to advance clean energy projects. As a general matter, 2 C.F.R. 200.1 defines what qualifies as federal financial assistance. The definition is broad, and EPA has determined it includes assistance that awardees or sub-awardees receive or administer, including sub-grants, subsidies, loans, and other financial instruments. Equity investments, however, are not eligible forms of financial assistance. This means that awardees and sub-awardees cannot purchase ownership interests in a solar company, for example.

In most cases, at least 75% of the award should go toward financial assistance to support low-carbon projects like residential rooftop solar or community solar installations, but in some instances the percentage is lower (65%). All remaining funds can be directed toward project-development technical assistance and program administration.

The Sabin Center identified approximately thirty awardees who have published enough information to enable us to determine, with relative precision, the specific types of financial assistance they plan to offer to support project deployment. From the options available under 2 C.F.R. 200.1’s definition, all awardees are considering offering some form of a grant or low-cost financing.

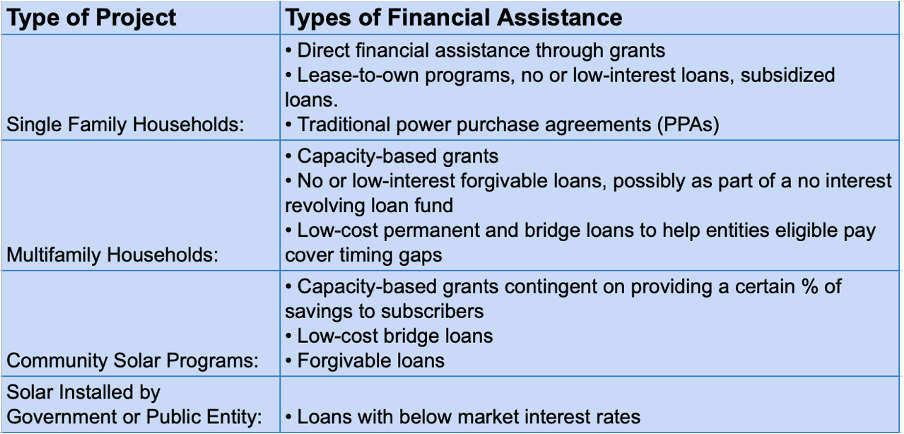

Table 1

Table 1 shows the common types of financial assistance that SfA awardees are planning to offer to help deploy solar and associated battery storage in the communities they serve. In particular, the use of direct grants to enable solar and battery storage for low-income single-family households looks likely to be a keystone of many SfA offerings. Additionally, bridge loans – a short term loan used while awaiting another financial arrangement – could become a staple SfA offering as eligible entities seek to take advantage of the IRA’s direct pay tax mechanism and transferability of IRA tax credits. These loans can provide upfront capital, with repayment occurring once tax credits are received or are successfully transferred. The financial tools in Table 1 align with the SfA’s goal of increasing low-carbon technologies in low-income and disadvantaged communities as the products and assistance are intended to reduce barriers to entry in the renewable energy market (e.g., direct grants) and make long-term investment more feasible (e.g., low-interest and forgivable loans).

More financial assistance and products may develop over the course of SfA planning periods, but local governments, households, community-based organizations, developers, and other stakeholders can, at the very least, use the publicly available information to plan for the rollout of SfA in their communities. As offerings take shape and become available, awardees, local governments, and other stakeholders would do well to track implementation and evaluate which strategies succeed and which face challenges. Adapting SfA offerings in a challenging political landscape may play an important role in the program’s success.

Project-Deployment Technical Assistance

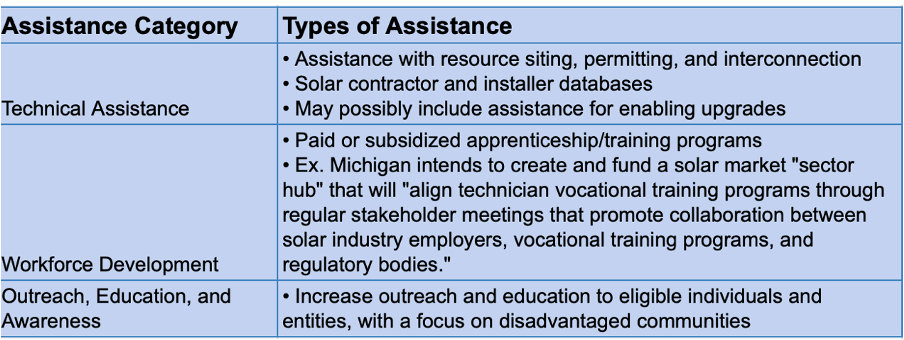

SfA grantees are authorized to use funds not allocated for financial assistance to “offer services and tools . . . to communities and energy stakeholders to overcome non-financial barriers to solar deployment.” SfA awardees are still developing these supporting initiatives, but they are likely to fall into three broad buckets, as shown in Table 2: (1) technical assistance; (2) workforce development; and (3) outreach, education, and awareness.

Table 2

Technical assistance with siting, permitting, and interconnection issues can help overcome non-financial barriers to residential deployment of solar by streamlining a process that can be cumbersome. Many SfA awardees have indicated that they will offer these types of technical assistance as complements to their suite of financial tools. For example, Tennessee’s SfA application stated that it would use 80% of its funds for financial assistance and approximately 11% total for technical assistance and workforce development. At this point, planned workforce development activities are largely focused on providing community residents with paid opportunities to train as solar installers. Still, creative strategies are being developed, like in Michigan, which plans to convene stakeholder meetings to “promote collaboration” between regulators, employers, and training programs to help identify workforce education gaps and workers meet the demands of the solar industry. The last assistance category – outreach, education, and awareness – is the least developed, but what information there is suggests that awardees will deploy funds to ensure that community members are aware of SfA opportunities and the associated climate and economic benefits of upgrading to solar energy and other low-carbon technologies, including participating in a community solar project.

Conclusion

Successful implementation of the SfA program is critical for advancing clean energy access in low-income communities across America. Despite the benefits this could bring, the Trump administration has been actively working to undermine the program, creating challenges for SfA awardees. Decisive court wins have provided relief, but the program remains at risk.

As explained above, SfA awardees are still relatively early in their planning processes, but have started to define the contours of their programs, detailing the types of financial and technical assistance they will provide. Their ability to implement their plans will depend, very much, on what EPA does next.

Vincent M. Nolette is the Sabin Center's Equitable Cities Climate Law Fellow.