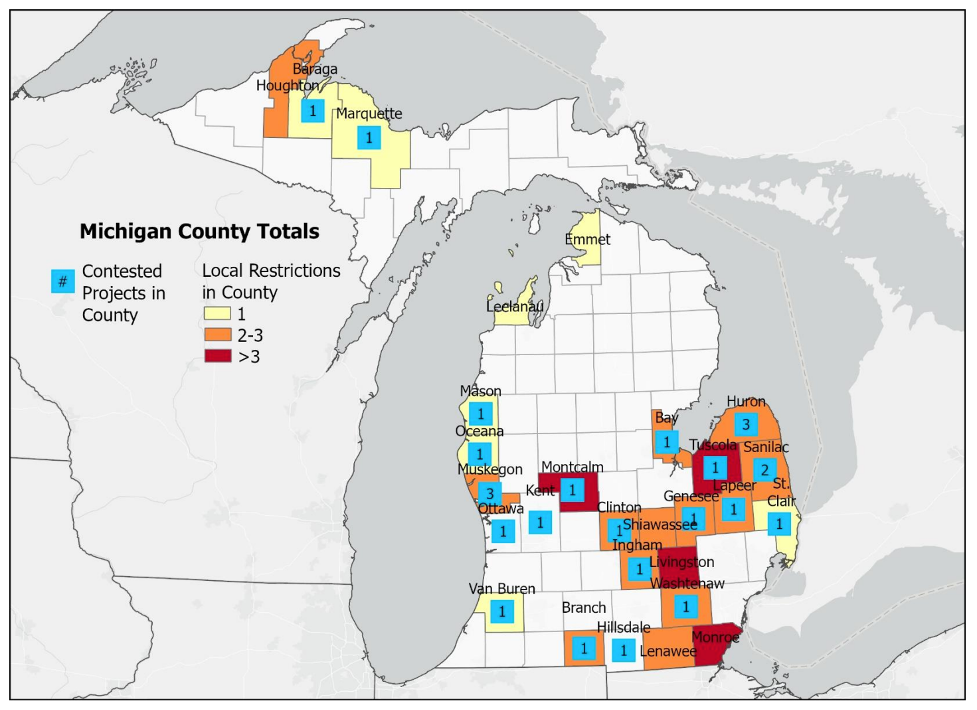

Over the last 10 years, dozens of townships in Michigan have effectively halted renewable energy development by adopting severe zoning restrictions, such as moratoriums. Many of these local restrictions, however, may become moot after November 29, 2024, when a new state law that reforms the siting process for large-scale wind, solar, and battery storage projects goes into effect. But significant questions remain as to how the law will be implemented.

The new law, Public Act 233 of 2023, seeks to rein in the proliferation of severe local restrictions by (a) establishing limits on the restrictions that local governments can adopt and (b) allowing the Michigan Public Service Commission (PSC) to step in when local governments exceed those limits. Under the new law, the state PSC will assume control over wind projects of at least 100 MW, solar projects of at least 50 MW, and battery storage projects of at least 50 MW, unless the local government where the proposed project is located adopts a compatible renewable energy ordinance (CREO) that is “no more restrictive” than state requirements. In the event that the PSC assumes control over an application, it will be allowed to preempt any local restrictions that would otherwise apply.

However, the new law provides only limited guidance as to what a CREO can or cannot include. The new law defines a CREO as “an ordinance that provides for the development of energy facilities within the local unit of government, the requirements of which are no more restrictive than the provisions included in section 226(8)” of that statute. The law further explains that “[a] local unit of government is considered not to have a compatible renewable energy ordinance if it has a moratorium on the development of energy facilities in effect within its jurisdiction.” The problem is that section 226(8) of the statute, which is supposed to set the benchmark as to how restrictive a CREO is allowed to be, only establishes clear limits on a few types of restrictions, such as setbacks and noise requirements. The statute does not explicitly address other types of restrictions that could just as easily kill renewable energy projects, such as blanket bans on projects in agricultural or industrial zoning districts or on land enrolled in the state’s farmland and open space preservation program.

Last month, the Sabin Center and partners from University of Detroit Mercy School of Law submitted comments urging the Michigan PSC to provide greater clarity on what constitutes a CREO within the meaning of the new statute. As we explained in those comments, the question of what constitutes a CREO is critically important, as it will determine in large part whether the local government or the state PSC will have jurisdiction to approve or deny a particular application. At a granular level, we urged the state PSC to make clear that an affected local unit of government does not have a CREO if it: (A) prohibits utility-scale wind, solar, or energy storage projects from agricultural or industrial zoning districts; (B) prohibits projects from land enrolled in the farmland and open space preservation program pursuant to PA 116; or (C) prohibits projects beyond a specified distance from existing transmission lines. As we argued, it is reasonably intuitive that these types of provisions can be more restrictive than many of those explicitly addressed in the statute. For example, a blanket ban on the use of farmland for solar development can be far more restrictive than the maximum setback requirements or noise restrictions allowed under the statute; indeed, in some townships, virtually all of the land suitable for utility-scale solar is farmland, such that prohibiting solar on farmland is a de facto ban. However, the statute offers very little guidance as to the precise circumstances under which the PSC could obtain jurisdiction over an application in a township or county that prohibits the use of farmland for these projects.

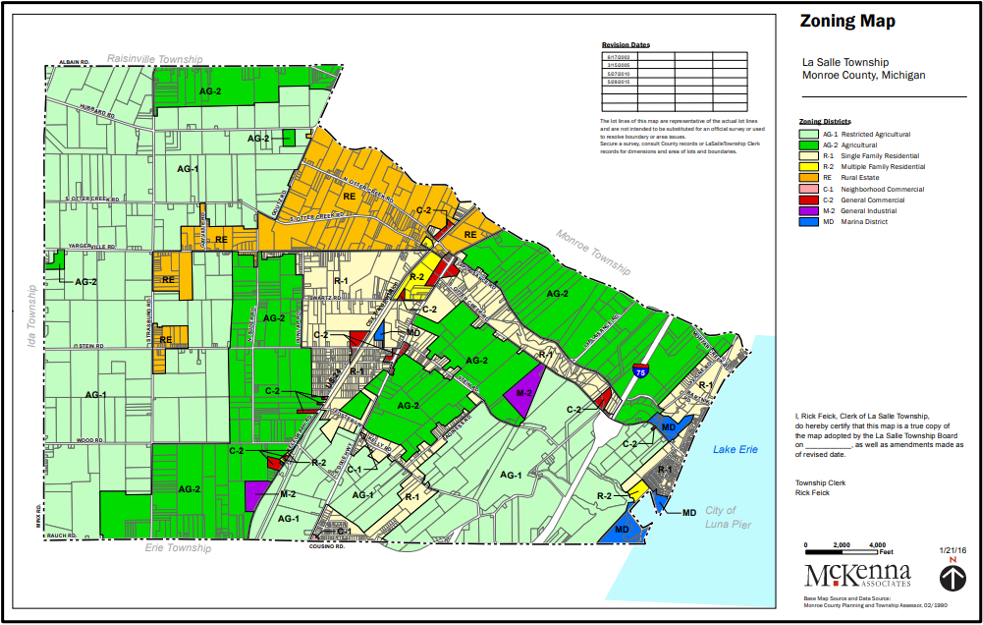

Without guidance from the PSC, these three types of restrictions could cause significant confusion and delay in the siting process. As of December 31, 2023, at least seven townships in Michigan had adopted ordinances that prohibit utility-scale solar development from agricultural zoning districts. In one—LaSalle Township (Monroe County)—a local ordinance adopted in 2022 restricts utility-scale solar to the township’s industrial districts. By some estimates, LaSalle Township’s industrial districts comprise only 89 acres out of approximately 17,000 acres in the township, and almost half of the land in those industrial districts is already developed. The township’s agricultural zoning districts, by comparison, comprise approximately 14,000 acres. Thus, the provision restricting solar to industrial districts is a de facto ban.

Importantly, in the absence of clear guidance from the PSC, local governments hostile to renewable energy development are continuing to adopt new restrictions even as the implementation date of the new state law rapidly approaches. As recently as June 27, 2024, the Planning Commission in Deerfield Township (Lenawee County) voted to recommend adopting new restrictions on renewable energy development that would (i) limit utility-scale wind and solar projects to within 1,250 feet of one existing transmission line; and (ii) prohibit utility-scale solar projects from any properties enrolled in the PA 116 program. Like the restrictions on solar development in agricultural zoning districts in LaSalle Township, these two restrictions in Deerfield Township could place a significant amount of land off-limits to development; the prohibition on the use of land enrolled in the PA 116 farmland and open space preservation program is also inconsistent with a state law that explicitly allows PA 116 land to be used for solar development.

With almost four months remaining until the new siting process goes into effect, there is still time for the Michigan PSC to resolve these important questions, but it is running out fast. Clear guidance on what constitutes a CREO could avoid significant problems in November and help to ensure that the statute succeeds in reining in local restrictions that unreasonably hinder development.

Matthew Eisenson is a Senior Fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, where he leads the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative (RELDI).