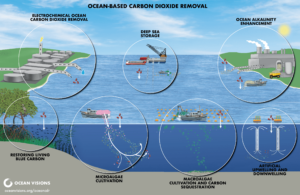

Ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is attracting increased attention as a possible climate change response strategy. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has made clear that, while CDR cannot substitute for rapid and deep cuts in emissions, its use is “unavoidable” if the worst impacts of climate change are to be avoided. According to IPCC estimates, a minimum of 6 gigatons of carbon dioxide will likely need to be removed annually by 2050 to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Currently, though, the largest technological CDR facility in operation anywhere in the world is only capable of removing just 4,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually. Clearly there is a long way to go and ocean-based CDR approaches could help us get there. Several of the ocean CDR approaches currently under consideration are thought to be highly scalable, with some (e.g., ocean alkalinity enhancement) theoretically able to remove 1 gigaton or more of carbon dioxide annually. Further research is, however, needed to determine whether these theoretical maximums can be achieved and answer other key questions about the efficacy and impacts of ocean CDR. Indeed, a recent report by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences concluded that “[t]he present state of knowledge on many ocean CDR approaches is inadequate,” and called for the establishment of a multi-billion research program. Conducting the necessary research is, however, likely to be challenging for a host of reasons. In a new paper published today, the Sabin Center explores the governance challenges associated with ocean CDR research and (if deemed appropriate) deployment.

Many of the remaining questions about ocean CDR can only be answered through controlled field trials in the ocean and, in some cases, relatively large-scale and/or long-duration trials may be required. That sort of in-ocean activity could raise a host of issued under international law. The ocean is a globally shared resource and, as such, a number of international agreements have been developed to govern ocean-based activities. Most of the relevant agreements pre-date discussion of ocean CDR and adapting them to this new class of activities has proved challenging.

In a new paper – International Governance of Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal: Recent Developments and Future Directions—I explore the treatment of ocean CDR under three key international agreements governing ocean-based activities. These are: (1) the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS); (2) the 1972 Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of wastes and Other Matter (commonly known as “the London Convention”); and (3) the 1996 Protocol to the London Convention (commonly known as “the London Protocol”). The paper explores the challenges inherent in applying these decades-old agreements to ocean CDR and suggests an alternative approach to governance grounded in the new Agreement under UNCLOS on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (the so-called “BBNJ Treaty”).

Read the full paper here.

Romany Webb

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.