By Amy Turner

Earlier this month, groups supporting the City of Berkeley, California filed six amicus briefs in the appellate proceeding California Restaurant Association v. City of Berkeley, currently before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. At issue in the case is whether the U.S. Energy Policy & Conservation Act (EPCA), which sets nationwide energy conservation standards for many common appliances and preempts state and local standards, preempts Berkeley’s 2019 ban on natural gas connections to newly-constructed buildings. (A refresher on the case, and on the District Court ruling from which the California Restaurant Association appealed are both linked here.)

While there is much to be said about the many arguments offered by Berkeley and the amici as to why EPCA does not preempt the Berkeley Ordinance, this post focuses on four of the amicus briefs – those submitted by the U.S. Department of Energy (the “DOE Brief”), the California Attorney General on behalf of eight states and two cities (the “States Brief”), a group of energy and environmental law professors (the “Law Professors Brief”), and three associations of local governments (the “Local Government Brief”) (authored by the Sabin Center) – which, together, offer a compelling and comprehensive view of the complementary but distinct regulatory areas over which the federal, state, and local governments exercise jurisdiction with respect to overlapping facets of building electrification.

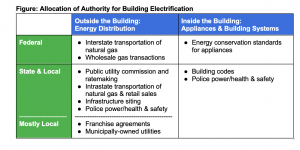

The process of converting to all-electric buildings – or, in other words, of phasing buildings off of gas and other fossil fuels – involves two spheres: the appliances and building systems inside of a building, and the energy system outside of it. Simply put, a building’s systems and appliances have to be capable of being powered by electricity, and electricity must be delivered to a building to the exclusion of fossil fuels. Each of these spheres is regulated at the federal, state, and local levels. The amicus briefs, taken as a whole, lay out how these overlapping regulatory spheres and jurisdictions relate to one another. And while each brief focuses on the domain of the agency or group submitting it (and the law professors’ brief discusses state and local authority under the U.S Natural Gas Act, among other things), they paint a remarkably consistent picture with respect to cooperative federalism as it is applied to building electrification.

Building & Appliance Energy Use

The allocation of authority for the regulation of building and appliance energy use is perhaps the headline issue of the proceeding (while the question presented is more formally whether EPCA preempts the Berkeley Ordinance, the one-level-down analysis asks, essentially, who has the authority to regulate what when it comes to appliance energy use). It is beyond dispute that the federal government, through regulatory standards promulgated pursuant to EPCA, has the authority to set – and does set – energy conservation standards for many common consumer and industrial appliances. By the same turn, EPCA preempts state and local “regulation[s] concerning the energy efficiency, or energy use” of appliances already regulated by EPCA. While the parties in CRA v. Berkeley disagree on the meaning of EPCA’s preemption provision, the four amicus briefs discussed here do not. The DOE Brief states that EPCA preempts “only those state actions that directly regulate the energy use of covered products,” and not “[l]aws that regulate other activities and have only an indirect effect on the quantity of energy used by a covered product.” (DOE Brief 8). As the States Brief points out, EPCA appliance regulations, and the preemption of conflicting state and local energy conservation standards, are aimed at avoiding a “patchwork of differing State regulations which would increasingly complicate their design, production and marketing plans.” (States Brief 21, quoting S. Rp. No. 100-6 at 4). This purpose is helpful to bear in mind when considering what state and local actions are not preempted by EPCA.

In assuming authority for energy conservation standards for appliances, EPCA leaves to the states and local governments authority to regulate in many areas that may, as the District Court put it, “have some downstream impact” on EPCA-regulated appliances. In particular, states and municipalities have the police power, or the state and local power to regulate with respect to resident health, safety, and welfare. As described in the Local Government Brief, the police power is retained by the states under the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, and delegated in some way by most states to local governments. The health and safety impacts of natural gas are well within the scope of the police power. Berkeley relied heavily on this authority in enacting the Ordinance, citing in the law’s legislative findings concerns about local air pollution, seismic risk and risk of wildfire, climate impacts, and “environmental and health hazards provided by the consumption and transportation of gas.” (Local Government Brief 9). Many forms of climate action may find their basis in the police power, especially as municipalities continue to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make their communities more resilient in order to blunt the harmful impacts of climate change. Fossil gas-reducing policies not only combat climate change, but also address the other dangers Berkeley cited.

The DOE Brief argues powerfully on behalf of the state and local police power by highlighting the mismatch between the process through which DOE may offer state and local governments waivers to EPCA preemption. To qualify for such a waiver, a state or local standard must produce energy savings that “outweigh its overall costs… But state regulations aimed at health and safety goals such as fire safety or the avoidance of pollution may not produce any energy savings… and they are unlikely to be justified on that basis.” The DOE Brief continues: “It is highly implausible that Congress intended to preempt both state energy conservation standards and health and safety laws but created a pathway for waivers that only appears to accommodate the former.” (DOE Brief 11). In short, “[h]ealth and safety regulations that indirectly affect the energy usage of appliances are neither new nor threatening to the federal regulatory scheme.” (DOE Brief 24).

In contrast to appliance energy conservation, building energy conservation is regulated by state and local governments. With respect to new and some renovated buildings, this regulation usually takes the form of a building code. (Non-building code regulation of energy conservation in existing buildings has generally been viewed as an exercise of the police power. State and local laws relating to the decarbonization of existing buildings do not yet widely target building electrification.)

The lines between building and appliance energy use can be fuzzy; after all, the energy use reflected on a building’s energy meter is in fact consumed by the building’s appliances. States and local governments with building code authority can regulate aspects of building design that implicate EPCA-regulated appliances so long as they do not actually set energy conservation standards for them. The Local Government Brief notes that there are numerous provisions of the International Building Code, a model code adopted by most states and many local governments, that address appliance pipes, fittings, wiring, monitoring systems, and more. (Local Government Brief 22-24). These model provisions have been adopted in countless building codes around the country and, though they tangentially relate to EPCA-regulated appliances, states and local governments with building code authority are within that authority to regulate them. (For building codes that do contain energy conservation standards for appliances, an exemption to preemption is available under EPCA, but authority for appliance energy conservation regulation rests with the federal government, which sets the terms of the exemption.)

Energy Distribution

With respect to the second regulatory sphere relevant to building electrification – the energy distribution system – the allocation of federal, state, and local authority is relatively straightforward. The Law Professors’ brief (authored by UCLA) explains this plainly: “The federal government regulates wholesale transactions and transportation in interstate commerce, while state and local governments regulate local distribution and retail sales (among other things”). (Law Professors Brief 8). The Federal Power Act and the Natural Gas Act expressly carve out local distribution from the federal domain, with the NGA in particular excepting “local distribution of natural gas” and the “transportation or sale of natural gas” other than in interstate commerce. (Law Professors Brief 10, citing 15 USC s 717(b)). The DOE brief similarly relies on the Natural Gas Act and its interpretive case law in noting that “all aspects related to the direct consumption of gas … remain within the exclusive purview of the states.” (DOE Brief 23, quoting South Coast Air Quality Mgmt. Dist. v. FERC, 621 F.3d 1085, 1090 (9th Cir. 2010)). Thus, while the federal government plays an important role in the federalist energy regulatory system, it does not make decisions regarding local distribution, the subject of Berkeley’s ordinance.

The Natural Gas Act’s carve-outs for state and local governments impliedly include a wide-ranging set of regulatory charges. Two elements of energy regulation – ratemaking and intrastate sales – generally fall to state public utility commissions, (Law Professors Brief 9), and while gas and electric ratemaking are essential facets of equitable building electrification policy, they are not generally understood to be in the local regulatory domain, nor are they the subject of the Berkeley ordinance, subsequent litigation, or pending appeal.

More relevant to building electrification is state and local authority to make siting decisions with respect to gas infrastructure (i.e., “local distribution”). Berkeley’s ordinance is essentially a gas infrastructure siting decision. Rather than, perhaps, limiting the extension of a gas line to a new subdivision or area of the community, the city decided to disallow the siting of gas piping on properties with new buildings. The States Brief notes that, consistent with the Natural Gas Act carve-outs, “[t]he power to regulate distribution infrastructure – the pipes that bring gas and wires into homes and buildings – is precisely the power that Berkeley has exercised.” (States Brief 28). The DOE Brief affirms this area of state and local authority by highlighting the “regulatory void” that would result if states and local governments could not enact an ordinance like Berkeley’s (DOE Brief 23). The federal government has no authority to act in the way Berkeley did; the Natural Gas Act expressly forbids it. Absent a comprehensive reworking of the Natural Gas Act by Congress, states and local governments must be the ones with authority to site, or not, new natural gas infrastructure.

Closely related to this state and local siting authority is the police power, which is important in both the building regulation and energy distribution contexts. Because there are fifty states across the US, some of them with more than one legal framework applicable to local government, the lines between state and local authority are not as clear as those between federal and state jurisdiction. That said, most state governments delegate some or all aspects of the police power to local governments, as California does to its local governments. Local governments may exercise that authority so long as they are not preempted by state or federal law. Moreover, many states also delegate some authority for gas distribution to local governments, particularly through the ability to enter into franchise agreements with gas utility companies or to create their own municipally-owned utilities. (Law Professors Brief 13-14). Both of these are the case in California, although Berkeley’s gas service is provided by an investor-owned utility. A municipal-utility franchise agreement sets the terms of a utility’s access to the public right-of-way in order to install infrastructure (lay gas piping) used to provide its service. These agreements demonstrate local authority for gas infrastructure siting, both inherently through access to the right-of-way and sometimes expressly in other provisions regarding extension or removal of service lines. Even more to the point, a municipally-owned utility will make direct decisions about where to site gas infrastructure or provide service. The siting decisions made in a franchise agreement or by a municipally-owned utility are part of the “local distribution” authority carved out from federal control by the Natural Gas Act and delegated by a state to local governments. (And as the Law Professors’ Brief points out, this authority may overlap with the police power, as when a municipal utility shuts off power to reduce wildfire risk. (Law Professors Brief 14, citing 2021 Sacramento Municipal Utility District Wildfire Mitigation Plan 30-31)). Thus, while no universal rule dictates the allocation of authority between states and local governments, in many places across the country, significant aspects of oversight over “local distribution” rest with local governments.

Conclusion

While the Ninth Circuit’s eventual ruling will help to affirm or reshape this analysis, it is safe to say that the lines of federalism applicable to building electrification have already been drawn. The federal government has authority over aspects of building electrification that are national in scope: interstate transmission and wholesale gas transactions, and setting nationwide market energy conservation standards for appliances (notably the federal government has some authority over other appliance rules, such as air pollution standards, but has not exercised it – meaning that states and local governments are not preempted from setting such standards, either). State and local governments retain the aspects of building electrification policy that remain. States are almost universally responsible for ratemaking and for some or all intrastate transmission and retail sales. And local governments, assuming they’ve been delegated authority by their states, make local distribution and siting decisions, and use their police powers to protect resident health, safety, and welfare. Building code-type construction requirements are also within the purview of state and local governments, albeit with more variation across states. Taken as a whole, the system of cooperative federalism set out in the four amicus briefs assessed here draws the map for action on building electrification. While not without hard questions in respect to specific actions, the blueprint is relatively straightforward for federal, state, and local policymakers alike.

Amy Turner is the Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.