Last month, the Sabin Center announced our new Cities Climate Law Initiative, a project aimed at helping U.S. cities achieve their climate mitigation commitments by addressing critical gaps or obstacles to advancing implementation of the laws and legal tools available to help reduce urban greenhouse gas emissions. The Initiative is conducting foundational legal research on the policy approaches being used by cities to reduce the carbon footprints of their buildings, transportation, energy and waste sectors. The Initiative is also working directly with urban sustainability offices and city attorneys to address legal questions arising in connection with carbon mitigation efforts.

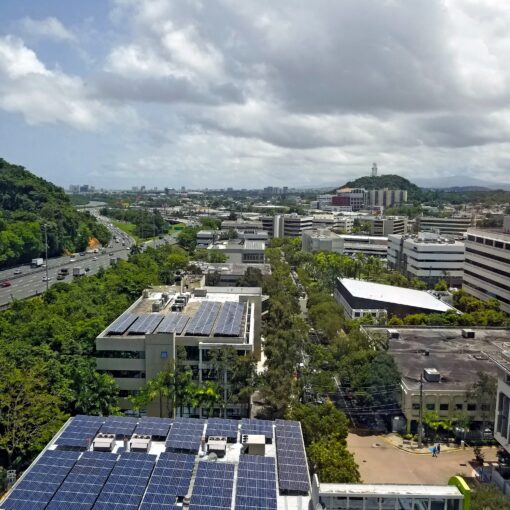

U.S. cities are growing, and they are increasingly taking the lead on climate mitigation. (So, too, are towns, counties and other municipal governing bodies – for ease of writing, we refer only to “cities” here but are focused on all forms of local government.) Dozens of U.S. cities have set greenhouse gas mitigation targets, more than 400 U.S. mayors signed onto a joint commitment to “adopt, honor and uphold the Paris Climate Agreement goals,” and more than 90 American cities have committed to a 100% renewable energy target. These goals—whether framed as “80×50,” carbon neutrality, or 100% renewable energy—are necessarily bold. And they demand that we not only fundamentally reimagine our economy and energy systems but also rethink the legal mechanisms by which we authorize and regulate our transportation, buildings, energy and waste, and the countless pieces of our lives these sectors touch.

Cities are out front on climate change, and are developing policy tools that can be used to help achieve these laudable objectives. These include direct regulation of existing buildings and changes to building codes, modal transportation shifts and electric vehicle adoption, spurring utility-scale and local distributed renewable energy, managing waste streams, engaging the private sector, and much more. But the challenges to cities are myriad. There are, as of 2017, 35,748 municipal and township governments and 3,031 county governments in the U.S. (there are another 38,542 “special district” local governments), and no two of them are exactly the same. In particular, cities are political subdivisions of the states in which they are located, meaning that they have no more authority than their respective states have granted them. Municipal enabling statutes, which grant cities the authority to enact laws and policies, look different from state to state and, in some cases, vary among cities in the same state. So while there are shared legal challenges that all cities face in enacting climate-friendly laws and policies, there are also significant differences in the types of policies cities may be able to enact, or at least in the way they would need to go about implementing them.

There are five major types of legal challenges that U.S. cities face in crafting and adopting climate-friendly laws and policies (there are many more challenges cities face from a legal perspective as well, such as litigation from local residents and groups):

- U.S. cities must be aware of significant and fundamental limitations of U.S. federal law. Federal laws like the U.S. Clean Air Act and the U.S. Energy Policy & Conservation Act can preempt some of the exciting policies advanced in places like London, which has implemented a “low emissions zone” (or LEZ) and an “ultra low emissions zone” (or ULEZ) that restrict, through tolls, road access for high-emissions vehicles in a central business district. While U.S. cities could be preempted by these federal laws from implementing a LEZ that distinguishes among vehicles based on emissions or fuel economy, there are important lessons, and aspects of these policies, that can be successfully implemented here in the U.S. For example, while laws restricting access to roads based on use of low emissions vehicle technology might be preempted, cities have significant latitude (depending on state enabling laws) to regulate traffic, including size and weight of vehicles, curbside parking, stopping and idling, and even closing sections of roads to vehicle traffic altogether. The Cities Climate Law Initiative helps U.S. cities generally and individually understand what aspects of LEZ policy are legally permissible and can be deployed to reduce a city’s greenhouse gas emissions.

- What’s doable in one U.S. city may not be permissible in another. Laws requiring new commercial and multifamily buildings to connect to renewable energy or be solar-ready (Seattle, WA), to install green roofs or other alternative measures (Denver, CO), or to be EV-ready (Los Angeles, CA) may require more creativity to implement in cities that don’t have authority to set or amend their building codes. That creativity may come in the form of increased incentives for the desired carbon mitigating measures, greening the city’s own buildings and operations, or attaching the requirement to another legal mechanism, as Boulder, CO, has done in requiring residential buildings to achieve certain energy efficiency requirements before obtaining a rental permit. We help cities understand the contours of their authority when it comes to replicating laws and policies seen elsewhere, and help develop best practices and policy elements that can translate across municipalities regardless of the authority they have been granted by applicable state enabling statutes.

- Challenges can also arise in traversing the boundaries of city and state authority. Cities are delegated their authority to enact laws by state enabling statutes. While some cities, such as those in home rule states, have generally more authority to legislate, all U.S. cities are limited by their grant of authority from the state. Therefore, cities will need to work with their state governments to implement some of the most promising climate-friendly policies. For example, New York City had explored congestion pricing proposals for decades, but, without authority to set tolls, it was unable to implement such a system on its own. In 2019, the city and state governments worked together to pass congestion pricing legislation in the New York State legislature (the program itself is expected to go into effect in 2021). In the waste sector, an increasing number of states – more than a dozen, at last count – are passing laws preempting municipalities from banning single-use plastic bags. Waste is a small but significant part of a city’s carbon footprint; 11 of 12 U.S. members of C40 Cities reported waste as comprising between two and six percent of each city’s greenhouse gas emissions.[1] Cities may need to work with states, if possible, to pass the laws that are necessary to limit the emissions associated with recycling or landfilling plastic or other waste. Public service commissions, also, are creatures of state law, and cities may need to work with these entities on matters as varied as renewable procurement, distributed generation and EV charging.

- Emerging entrepreneurial ventures offer opportunities and legal hurdles. Cities have seen a proliferation of shared micromobility companies, which offer bicycles or scooters (sometimes electric) for rent for local trips. Micromobility can help reduce vehicle trips, and their associated greenhouse gas emissions, by offering a flexible mobility option that can complement public transit. Aggressive pushes by micromobility companies to introduce their bikes and scooters have, at times, left cities scrambling to figure out whether and how to allow micromobility companies to operate, and how to regulate various legal issues relating to public rights-of-way; insurance, indemnity and bonding; safety; parking; data sharing; customer service; device types; and permitting.[2] At this point, dozens of U.S. cities have invited micromobility companies to do business within their boundaries, developing helpful ways to evaluate and stay ahead of the issues they raise, including through pilot projects and by adapting legal structures for these programs from other cities. Strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, including from private businesses, are sure to continue developing rapidly. The Cities Climate Law Initiative helps cities develop best practices and legal approaches to facilitating and regulating some of these strategies.

- Climate action may depend on contractual arrangements between non-city parties. The bulk of cities’ greenhouse gas emissions reductions will result from the actions of those who live and work in them. Cities can mandate and incentivize carbon-reducing measures, but private companies and individuals will need to take action for cities to be successful in achieving their goals. One example: New York City’s new law mandating carbon emissions caps for large buildings. The law’s mandate is clear and the penalty is significant, set at $268 per ton of carbon above a building’s cap, but ensuring compliance with the law will likely require building owners and tenants to realign traditional commercial lease terms, which disincentivize owner investment in building energy retrofits (often, the building owner pays for capital improvements while the tenant reaps most of the energy savings, a conundrum referred to as the “split incentive problem”). Compliance with New York’s new law will, in many cases, require energy upgrades to both the base building systems and the individual tenant spaces. In order to facilitate this, and ensure that New York City office buildings can comply with the law, commercial leases will need to be “green” or “energy aligned” leases, a departure from current leasing practices. The Cities Climate Law Initiative will study legal tools such as these, as well – those that aren’t entered into directly by the city.

Central to all of this, of course, is equity. The significant and structural legal changes that will be needed to achieve cities’ climate mitigation goals must be implemented in a way that is just, that protects vulnerable communities and that reflects the needs of all of a city’s residents. Some of the carbon mitigating measures discussed herein have the potential to create more equitable living conditions, as with Boulder’s rental licenses policy, which aims to improve the condition of Boulder’s rental housing stock. Others have the potential to be deployed in ways that improve equity or in ways that do further harm: micromobility could be used to serve “transit deserts” or reserved for wealthier areas already served by transportation options. Renewable energy procurement and generation have the potential to improve local air quality. These considerations are a significant part of crafting any laws, policies or legal tools that cities can use to combat climate change.

The Cities Climate Law Initiative is seeking U.S. cities, towns, counties and other municipal actors to partner with on challenging legal questions associated with climate mitigation policies. Together, the Sabin Center and each partner city will identify a legal question, issue or obstacle, or a drafting need. The Sabin Center will conduct academic research on the question to help inform each city’s approach to developing or implementing an identified climate mitigation policy and will provide tailored insights and learning to the city. The cities, in turn, will lend their perspectives to help facilitate additional learning by other U.S. cities and metro areas that are considering similar policies. In this way, the Cities Climate Law Initiative and its partner cities will help scale up use of some of the most promising legal tools available to assist in achieving quantified goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and bring new sources of renewable energy online.

For more information, or to discuss partnering with the Sabin Center and the Cities Climate Law Initiative, please contact Amy Turner at aturner@law.columbia.edu.

[1] Boston’s methodology appeared to differ from the 11 other cities, as it reported a zero percent share of waste in GHG emissions.

[2] Dockless Mobility Regulation, Practical Law Government Practice Law Practice Notes w-017-6569 (2019), available on Westlaw.