By Justin Gundlach and Romany Webb

The speedy and opaque process that ended in December 2017 with passage of the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has meant that different sectors and companies are just now figuring out what its provisions mean for them. For regulated utilities, which collect money from ratepayers in anticipation of needing to pay corporate taxes on various planned projects (a “deferred tax pool”), the cut effectuated a windfall whose sizeable scale is coming into focus as utilities file their quarterly financial disclosures with the Securities and Exchange Commission. As Politico has reported, New Jersey-based PSEG says it will have about $1.8 billion as a result of tax policy change, American Electric Power estimates $4.4 billion, and NextEra Energy $4.5 billion.

Unlike other businesses, utilities’ use of a windfall like the one arising from the new tax law is tightly constrained by state law and the public service commissions responsible for administering it. Utilities’ profits are tightly controlled in general; public service commissions only allow them to recover the costs they incur in providing services, plus a reasonable return on their investments. Commissions will, therefore, evaluate and possibly refuse or redirect utilities’ requested uses of the windfall. A debate is currently brewing over whether the windfall should be refunded to ratepayers or used to fund new projects that would otherwise require rate increases. These options are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but our view is that investment of this windfall in new projects is the most prudent option and dividends for shareholders the least.

In this blog, we suggest various utility projects that could be funded by the deferred tax pool windfall, each of which is likely to result in either improved customer service or rate reductions or both, over time. All of our suggested projects involve action by gas and electricity distribution[1] utilities to address climate change. As our suggestions reflect, distribution utilities have a unique opportunity to mitigate climate change, including by facilitating the transition to a clean-energy economy. They are also vulnerable to the effects of climate change, with much of the infrastructure they own and control likely to be affected by future extreme, climate-driven events like storms and heat waves.

Natural Gas

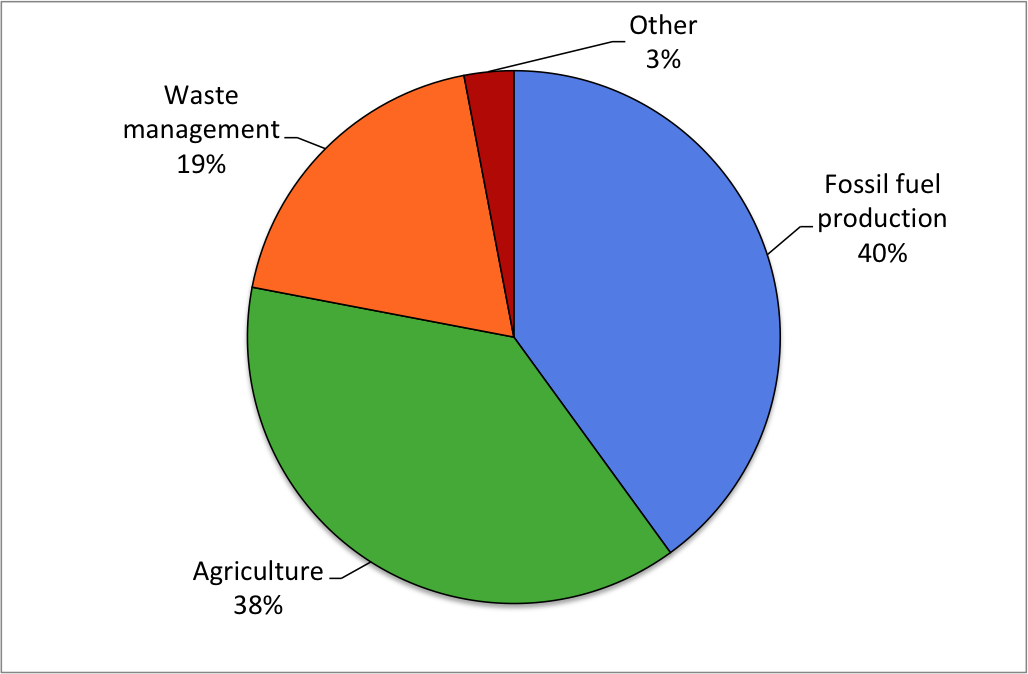

Natural gas utilities could use their deferred tax pool to address pipeline leaks which, as previously reported on this blog, have been found to occur every one to two miles in many areas. This results in the waste of a valuable resource, with the Environmental Protection Agency estimating that approximately $192 million worth of gas was lost through distribution pipeline leaks in 2011, the latest year for which data is available. It also has devastating consequences for the environment, including accelerating climate change, as natural gas is comprised almost entirely of methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide (on a per ton basis, over a 20-year timeframe). (See the Sabin Center’s previous post here for more information on leaks and options for addressing them.)

While most pipeline leaks are relatively inexpensive to repair, their sheer number makes instituting a comprehensive repair program costly. Thus, in the past, gas utilities have often argued that such programs would need to be funded through increased rates. The existence of the deferred tax pool makes rate increases unnecessary, however. The pool could be used to fund leak repair programs or the replacement of older leak-prone pipes. This would have broad social benefits, helping to mitigate climate change, while also lessening other safety risks (e.g., leaks trigger explosions). It is also economically efficient, avoiding gas losses, which currently impose a significant cost on ratepayers. Over time, as more leaks are repaired and associated gas losses decline, bills will be lower than otherwise. Using utilities’ deferred tax pools to fund leak repair is, therefore, a “win-win” that will benefit ratepayers and the public more generally

Electricity

Electric utilities have many worthy options for how to allocate their deferred tax pool dollars, but they should seriously consider the following two, because each would – in very different ways – deliver ongoing benefits to all stakeholders involved: the utilities, ratepayers, and everyone who is reliant on the electric grid and is affected by its ongoing reliance on fossil fuels.

Establishing EV charging stations. Supplanting the gasoline-powered internal combustion engines currently used in cars, trucks, and buses with electric motors would reduce several forms of pollution (particulates, nitrogen and sulfur oxides, greenhouse gases, and noise). As the transportation sector is now the leading source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, this sort of reduction is arguably as important as ever. What prevents a switch over to electric vehicles (EVs)? The market for EVs is subject to strong network externalities – meaning that the costs of buying and driving EVs will fall as more people buy and drive them. It is also subject to significant bottlenecks, chiefly access to charging stations (due to “range anxiety”) and the inconvenience of how long it takes to charge an EV battery. So, loosen those bottlenecks, sell more EVs, and a virtuous cycle of increasing sales could follow. But why should utilities care? Because supplanting gasoline-powered vehicle engines with electric motors would mean expanding utilities’ customer base and service offerings, and thereby bending the electricity demand curve upwards (it has been flat for about a decade). Establishing charging stations is not the only prerequisite to this virtuous cycle, of course, but as governments and companies alike have recognized, it is among the most significant – and expensive.

Climate change vulnerability assessments. In response to Superstorm Sandy’s tremendous and consequential damage to electricity distribution infrastructure, the New York Public Service Commission allocated funds for storm hardening measures and ordered the state’s distribution utilities to assess their vulnerabilities to climate change. These assessments are still underway, but it is already clear that undertaking them has led utilities to recognize in concrete and actionable ways a variety of risks that they face as a result of the higher temperatures, heat waves, precipitation, storms, and floods that climate change is bringing to the region. As we’ve written previously on this blog, one would think that coastal storms like Katrina, Sandy, and more recently Matthew, Harvey, Irma, and Maria, would be enough to prompt utilities and commissions to investigate and address vulnerabilities to the changing climate – not least because addressing those vulnerabilities is all but certain to save ratepayers money in the long run. Perhaps the combination of access to deferred tax pool dollars and the past year’s storms, floods, and wildfires will nudge more utilities and commissions to take similar steps.

Given their potential benefits, we encourage both distribution utilities and public service commissions to consider these options as they decide what should be done with the deferred tax pool.

[1] Distribution pipelines and power lines are used by utilities to deliver gas and electricity respectively to residential, commercial, and industrial customers. They can be distinguished from the transmission conduits that move gas from field production and processing areas and electricity from power plants to large volume customers and local utilities.

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.