By Michael Burger

Yesterday, three local governments in California (San Mateo County, Marin County and the City of Imperial Beach) filed potentially groundbreaking climate change lawsuits in California state courts, each one charging a group of 20 fossil fuel companies with liability for public nuisance, failure to warn, design defect, private nuisance, negligence, and trespass. (The complaints will be available in an updated version of this post as soon as we have them available.) This type of state common law climate litigation has been a long time coming, and these cases may well represent the first of a slew of similar cases nationwide. Here, I summarize several interesting aspects of the complaints, and offer some first blush thoughts on both the legal hurdles they might face and the potential outcomes they might produce.

The Lawsuits

Each of the complaints presents the same simple, compelling storyline: These fossil fuel companies knew. They knew that climate change was happening, that fossil fuel production and use was causing it, and that continued fossil fuel production and use would only make it worse. They knew this, but they hid it. And then they lied about it, and paid other people to lie about it for them. All the while they profited from it, and plotted to profit more. Ultimately, their actions caused sea levels to rise, and thereby caused harm, are continuing to cause harm, and are contributing to future harm to the plaintiff governments and their residents. Accordingly, the complaints claim that the defendant companies should be held liable and forced to pay, both for the costs the local governments are incurring to adapt to sea level rise and for the companies’ own willful, deceptive, and malicious behavior.

The named defendants include Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, Citgo, ConocoPhillips, Phillips 66, Peabody Energy, Total, Eni, Arch Coal, Rio Tinto, Statoil, Anadarko, Occidental, Repsol, Marathon, Hess, Devon, Encana, Apache, and unspecified “Company Does.” According to the plaintiffs, these companies are responsible for about 20% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that were emitted during the period from 1965 to 2015, an amount which the complaints argue is a “substantial portion” of the climate change problem. The “substantial portion” claim is legally significant.

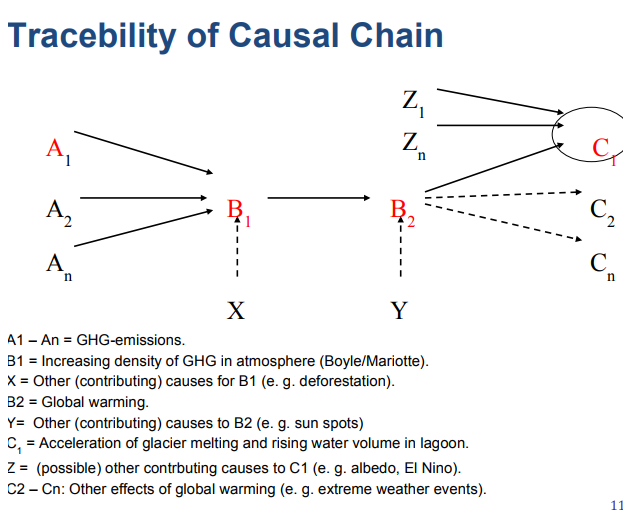

To show that the defendants are liable, the plaintiffs must demonstrate that they caused the alleged harms. Climate change, of course, is caused by many different actors; sea level rise and resulting impacts are attributable to climate change and, in some instances, other factors. Thus, it may be argued that the defendants are not the only parties who can or should bear responsibility, or blame. However, as a matter of law, causation can be shown by proving that the defendants are a “substantial factor,” or that they contributed significantly to the harm. Relying on a cumulative carbon analysis, plaintiffs make a strong case that that standard is met.

The timeframe plaintiffs employ for the cumulative carbon analysis is an important one, for both its legal and narrative impact. In rough terms, it corresponds with what Will Steffen calls the “Great Acceleration,” the years since the 1960s in which approximately 75% of all historic industrial emissions have occurred, and in which the rate of fossil fuel production and consumption has significantly increased. The specific years also mark notable bookends in climate change history. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Scientific Advisory Committee Panel on Environmental Pollution reported that unabated CO2 emissions would, by 2000, alter the climate, and Johnson charged Congress to address the problem. In 2015 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had just issued its Fifth Assessment Report, relaying the state of the art in climate science and understanding, and the global community signed the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The plaintiffs recite an increasingly well-documented, and familiar, timeline regarding what the fossil fuel companies knew and understood about climate change, and what they said and did (or did not do) about it. Several aspects of the story jumped out to me:

- In 1980, Imperial Oil (a Canadian company in which Exxon owns a super-majority stake), reported to Exxon and Esso that power plant carbon capture technology was technologically feasible, but that it would “double the cost of power generation.” (Carbon capture is not yet deployed at scale in the power sector.)

- Some fossil fuel exploration and production companies started climate proofing their own infrastructure around 20 years ago. They started investing in Arctic development capacity even further back, likely in anticipation of new exploration and production opportunities in a melting region.

- In 1988, industry fundamentally shifted its stance towards climate change, turning away from independent research and outward statements favoring action, and turning towards the strategies and tactics documented in Erik Conway and Naomi Oreskes’ Merchants of Doubt, further revealed through reporting by the Energy and Environmental Reporting Project at Columbia University, and the ongoing subject of investigations by New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and others. That year, according to the complaint, the political will to take on the climate change challenge was becoming increasingly evident. The insinuation one draws is that once industry sensed the real possibility of a commitment to international cooperation and domestic regulation it began to mount its overt and covert defenses.

- Current EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt was an active participant in fossil fuel companies’ coordinated effort to resist climate change regulations.

According to the plaintiffs, the consequence of the cumulative emissions put into the market by defendants, and of the disinformation campaign waged by certain industry leaders and the think tanks, communications shops, and lobbying operations they funded and hired, are rising sea levels that have already impacted local governments and residents, and that will continue to do so, in ever more extreme ways, in the years to come. These impacts include inundation of public beaches and coastal property, and more frequent and extreme flooding and storm surge, resulting in some permanent property losses and requiring expenditure of funds for impact assessment, as well as adaptation and emergency response planning and implementation.

And so they have sued, seeking damages, both compensatory and punitive, under a range of common law theories that place blame on and assign responsibility to these defendants because of their knowledge, their resistance to mitigation, and their various roles in fossil fuel exploration, production, marketing, and consumption.

The Legal Obstacles

Scholars and practitioners have theorized this type of climate action for years. For example, in 2011, my colleague Michael Gerrard wrote this piece, surveying a host of issues such cases will inevitably encounter, and Doug Kysar of Yale early on wrote this piece on how climate change may itself influence the future shape of tort law. Tracy Hester at the University of Houston has written this analysis of the different elements of state common law climate cases. Thinking on this goes further back, to the state common law public nuisance claims included – but never decided – in Connecticut v. American Electric Power.

Importantly, these cases have been filed at a particular moment in time, when scientific consensus on and understanding of climate change is at an all-time high but the federal government’s commitment to addressing the problem is at an all-time low. In fact, it’s in negative territory, with a president, an EPA administrator and an Interior secretary determined to ramp up fossil fuel production and consumption while doing nothing to mitigate emissions or adapt to impacts. And the fossil fuel industry’s active role in fighting against climate action continues to come to light, making comparisons to the tobacco litigation (like this one) increasingly accurate.

Without detracting from the many other legal issues likely to arise in the lawsuits, here are three that come immediately to mind.

Standing: The first issue that tends to come up in thinking about climate change litigation is standing. Standing is a threshold issue in any challenge to government action, or inaction, in the climate change arena. But these are common law tort claims. The elements of standing – injury, causation, redressability – constitute the merits of the case. Were plaintiffs harmed in a tortious manner? Did defendants cause that harm? Are plaintiffs entitled to damages? That’s the whole case, not a preliminary matter to determine jurisdiction. Accordingly, it seems that a standing challenge should not, in theory, succeed; at least, not before the merits of the case are determined. Nonetheless, standing was an issue in Connecticut v. AEP, where the Supreme Court was asked to rule on whether a federal common law public nuisance claim could proceed. In her opinion finding the federal nuisance claim displaced by the federal Clean Air Act, Justice Ginsburg noted that “[f]our members of the Court would hold that at least some plaintiffs have Article III standing.” Justice Sotomayor did not participate in that decision, meaning that Justice Kennedy voted to uphold his own opinion from Massachusetts v. EPA, which found states had standing to sue due to injuries they suffered from climate change. Thus, at the moment, there are likely at least five votes for the broad proposition that states have standing to sue for climate change. The opinion in Mass. v. EPA, however, relied on the “special solicitude” owed states due to their quasi-sovereign status. Here, plaintiffs are local governments, which may or may not be given a similar weighting by Justice Kennedy and others.

Political Question: In Connecticut v. AEP, the federal district court originally found that there were no judicially manageable standards by which to adjudicate a public nuisance claim brought by states, cities, national environmental organizations, and three private land trusts against five power companies, and that the cases raised a political question necessarily left for the political branches. The Second Circuit reversed this judgment, finding that courts have long adjudicated complex environmental nuisance cases, and that the political question doctrine did not pose a bar. The Supreme Court’s view of the matter is a little obscure. Justice Ginsburg noted that “at least four judges” found that neither standing nor any other “threshold obstacle bars review.” The infamous footnote 6 in that opinion refers to the political question doctrine, but neither it nor the text offers an explanation of exactly how the justices voted on the matter. All of which leaves the political question issue unresolved.

The 9th Circuit, in Native Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp., another federal common law nuisance case, did not directly address the political question doctrine, relying instead on the displacement analysis from Connecticut v. AEP. In Comer v. Murphy Oil, a Fifth Circuit panel found that the political question doctrine did not bar state tort claims brought against several companies for their contributions to climate change. However, that decision was later vacated in a uniquely bizarre procedural sequence.

The facts of this case, however, are different. Plaintiffs have framed their case not about climate change policy in the abstract, and not only about a specific quantity of emissions contributing to climate change, but also about these private actors’ individual and collective conduct, which includes not only producing GHG emissions but interacting with the market and with regulators in a sustained disinformation campaign. Plaintiffs are not seeking to establish a specific policy in regards to GHG emissions, public lands management, or other matters of federal agency discretion. Rather, they are seeking damages for harms caused by market behavior they claim was, among other things, knowing, negligent, and intentionally misleading.

Preemption: In Connecticut v. AEP, the Supreme Court found that a public nuisance case brought in federal court under federal common law had been displaced by the Clean Air Act. Because the Court had previously held in Mass v. EPA that EPA was authorized to regulate GHGs by the federal legislation, there was no longer room for federal common law. However, the court did not reach the state common law claims also plead in that case. It remains an open question whether state claims such as those plead here are preempted by federal legislation, including the Clean Air Act, the Mineral Leasing Act, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, and other statutes setting federal GHG emissions and fossil fuel extraction, transportation, and consumption policy. In Comer, the original Fifth Circuit panel concluded that federal preemption was inapplicable to plaintiffs state common law claims; but, as noted, that decision was vacated and has no precedential value. Its reasoning, of course, nonetheless bears consideration.

One preemption case that defendants may seek to invoke is the Fourth Circuit decision in North Carolina v. Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). There, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit dismissed a common law nuisance action brought by the state of North Carolina against TVA. The action focused on emissions from TVA-operated power plants in Alabama and Tennessee, which were alleged to cause air pollution and associated health problems in North Carolina. Even if this were the case, however, TVA would not be liable for public nuisance according to the Fourth Circuit. In reaching this decision, the Fourth Circuit noted that “[c]ourts have traditionally been reluctant to enjoin as a public nuisance activities which have been considered and specifically authorized by the government,” such as under the Clean Air Act. The Fourth Circuit reasoned that “TVA’s plants cannot logically be public nuisances where TVA is in compliance” with the Clean Air Act, and its plants have been permitted by the states in which they operate. Defendants will likely cite to this case to argue that federally permitted activities cannot be the subject of nuisance suits.

Assuming arguendo that North Carolina v. TVA was rightly decided (and there are arguments to be made that it was not), there is at least one key distinction between it and these newly filed cases – the facilities in that case were specifically permitted to pollute under the standards set through the Clean Air Act, and the permits in question authorized the pollution in question. Here, by contrast, none of the federal programs through which defendants have operated, and none of the foreign governments that have permitted them to operate in other jurisdictions, have thoroughly considered, far less sought to regulate, the downstream GHG emissions associated with their activities. What’s more, given the Trump Administration’s outright resistance to using the federal statutes to regulate GHGs at any stage there can be no conflict between state law and federal law, and state law cannot be said to be an obstacle to achieving any particular federal goals. Defendants might argue that state common law liability would conflict with the Trump Administration’s decision to not protect public health and welfare, or to pursue “energy dominance,” or some other such thing, but we have to hope that that line of reasoning will not find sympathetic audiences in court.

Possible Outcomes

As with the case of Juliana v. United States, currently winding its way towards a trial date next year, these cases face significant legal hurdles. Success on the merits is far from assured. But it could happen. The facts are there, making the case for causation and culpability, and the law can accommodate these claims. What’s more, if other cases in other jurisdictions are brought, we may ultimately see a large-scale settlement similar to the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, or perhaps establishment of a fund through federal legislation, along the lines of the Superfund program established under CERCLA.

However, and again as with Juliana, there are also potential outcomes short of success on the merits that could still advance the ball on climate change. For one thing, these cases represent a new pressure point on the fossil fuel industry, and a new spotlight on that industry’s engagement with climate law and policy. They make the case that these companies are bad actors, who have lied for years to continue to generate profits at the expense of the local governments and individual citizens and residents who bear the costs of climate impacts. The drama of the courtroom setting could mobilize the public’s interest and give life to local activism on these issues, much as Juliana has captured the youth climate movement and given it voice. Moreover, the prospect of judicial judgment affirming plaintiffs’ case might nudge these companies to accelerate their own transition away from past practices, towards new approaches to providing energy to consumers.

Romany Webb is a Research Scholar at Columbia Law School, Adjunct Associate Professor of Climate at Columbia Climate School, and Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.