Justin Gundlach

Climate Law Fellow

Over the past decade, as the scientific consensus about the fact and nature of anthropogenic climate change has solidified, extreme weather events have destroyed enormous sums of assets, infrastructure investments, and large numbers of human lives. Set against the backdrop of climate change, these events have prompted charged arguments over whether and how much climate change “caused” the occurrence or severity of a given event. The stakes—financial, legal, political—are often high, but the absence of agreed scientific standards has generally left these arguments unmoored from criteria that all parties are willing to accept as valid grounds for resolution.

This is the circumstance that the National Academies of Sciences hopes to address with its report, published on March 11, Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change. The new NAS report articulates three critical issues: (1) the grounds for and levels of confidence in the ability of science to accurately attribute the contribution of climate change to particular types of extreme weather event; (2) technical and rhetorical considerations for those developing and publicizing information about climate change attribution; and (3) an agenda for the scientific community to pursue in order to improve attribution science still further. Summaries of each follow after the jump.

One of the report’s recommendations—to develop “transparent community standards for attributing classes of extreme events”—deserves special mention because of its clear application to contexts in which a factfinder must determine causation and/or responsibility for adverse outcomes related to risks heightened by climate change. Such standards would provide clear guidance to non-experts faced with the task of classifying an event as climate change-related, or of classifying a risk heightened by climate change as foreseeably more intense or frequent. This kind of information would be not only useful but impossible to ignore wherever someone is responsible for anticipating risks heightened by climate change. Such community standards would therefore have immediate implications for insurers, civil and structural engineers, and possibly also state and local governments, among others.

These implications are sure to resonate in legal disputes, given that courts tend to struggle when asked to weigh probabilistic evidence of how much one cause affected the outcome of a multi-causal event. At a minimum, community standards would guide parties and courts in developing and interpreting evidence in cases like Illinois Farmers Insurance Co. v. Metro Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, and Saint Bernard Parish Government, et al., v. United States. In the first case, insurers that had paid for property damage from flooding around Chicago sought compensation from municipal authorities on the grounds that those authorities had been aware that climate change had heightened the risk of damaging floods in the region, yet had not upgraded the capacity of the municipal storm water control system. In the second case, plaintiffs alleged that the Army Corps of Engineers failed in its legal duty to protect parts of New Orleans from Hurricane Katrina.

1. As of now, how well can we attribute particular events to climate change?

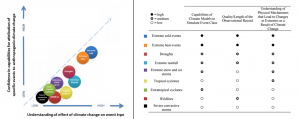

The report uses the graphic and table at right (click to enlarge) to su mmarize the state of attribution science in relation to different types of extreme weather event. Both depict how accurately analyses of a given event can attribute that event’s occurrence and/or severity to climate change. As the report explains, attribution science is better on some types of event than others. It can offer accurate answers about how much to attribute a heat wave, a cold snap, or the absence of cold weather to climate change. But it cannot yet offer with as much confidence answers about the role climate change played in the occurrence, duration, or intensity of a particular hurricane or wildfire.

mmarize the state of attribution science in relation to different types of extreme weather event. Both depict how accurately analyses of a given event can attribute that event’s occurrence and/or severity to climate change. As the report explains, attribution science is better on some types of event than others. It can offer accurate answers about how much to attribute a heat wave, a cold snap, or the absence of cold weather to climate change. But it cannot yet offer with as much confidence answers about the role climate change played in the occurrence, duration, or intensity of a particular hurricane or wildfire.

One point that should not be lost among the report’s scientific caveats is this: attribution science can now do an excellent job of explaining the role of anthropogenic climate change in some types of weather events.

2. Guidance for developing and describing estimates of attribution

At the press conference that launched the report, its lead authors emphasized that any effort to understand attribution in a given case should not begin with the question, “Was this event caused by climate change?” The report makes the same point and suggests two alternative questions: “Are events of this severity becoming more or less likely because of climate change?” and “To what extent was the storm intensified or weakened, or its precipitation increased or decreased, because of climate change?”

In addition to warning against simplistic “causal” framing, the report also discusses several items that scientists and those presenting scientific conclusions should consider. The list includes avoiding selection bias, deciding whether to analyze a given event in terms of frequency or magnitude, describing probabilistic effects using a “fraction of attributable risk” or a “risk ratio” rubric, and quantifying uncertainty, among others. These recommendations also touch on “rapid attribution and operationalization,” and caution that compressing analytic timeframes should be acknowledged to also reduce levels of confidence in a given attribution.

3. The agenda for future work

The report endorses the World Climate Research Programme’s list of ambitions for improving the understanding of climate, weather, their relationship to each other and their relationships to climate change. These include various improvements to climate models and remote sensor technologies, as well as continued efforts to develop a thorough historical observational record of key aspects of the climate. Other recommendations include how to minimize selection bias and, as noted above, the articulation of transparent community standards by which a given attribution can be measured.