By Jennifer Danis & Romany Webb

On Thursday, January 21, 2021, President Joe Biden appointed Richard Glick as the new chair of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Chairman Glick has been a FERC commissioner since November 2017, and has earned a reputation as a strong proponent of action on climate change during his tenure. In April 2019, in an article co-authored with his legal advisor Matthew Christiansen, Chairman Glick declared that, “[t]he evidence that anthropogenic climate change is an existential threat to our way of life is incontrovertible.” The article went on to note that FERC’s “actions have substantial consequences for climate change.” To date, those consequences have been largely ignored by FERC, but that could soon change.

Chairman Glick has been a particularly outspoken critic of FERC’s approach to approving new fossil fuel infrastructure. He has lambasted his fellow commissioners for not grappling meaningfully with the climate impacts of infrastructure approvals in his strong dissents to recent pipeline certifications. Importantly, he does not simply argue that FERC should consider climate impacts, but that it must do so to meet its statutory obligations. As he said in one recent decision: “The Commission once again refuses to consider the consequences its actions have for climate change. A public interest determination that systematically excludes the most important environmental consideration of our time is contrary to law, arbitrary and capricious, and not the product of reasoned decision-making.”

As current and former commissioners often point out, FERC is not an environmental regulator. Rather, it is charged with protecting the public interest by regulating the energy sector, with the primary goals of ensuring reliable electricity and natural gas supplies at reasonable prices. Thus, for example, FERC cannot directly regulate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the energy sector. But, it can and must account for the GHG impacts of its orders and policies. This is particularly important when FERC is considering approving new natural gas pipelines and other infrastructure that threaten to lock-in continued fossil fuel use at the expense of cleaner energy sources.

FERC is responsible for approving the construction and operation of pipelines used in the interstate transportation of natural gas (interstate pipelines), as well as facilities used to import and export natural gas overseas (LNG facilities). Under the Natural Gas Act (NGA), FERC can only approve an interstate gas pipeline if it determines that the pipeline “is or will be required by the present or future public convenience and necessity,” which has been held to require an evaluation of “all factors bearing on the public interest.” FERC also applies a “public interest” test when determining whether to approve LNG facilities. Importantly however, under the NGA, LNG facilities are presumed to be consistent with the public interest unless the record shows otherwise. This may change, as amendments proposing to eliminate the LNG presumption of public interest were introduced in the last Congressional session, and could surface again. There is currently no presumption of public interest with respect to interstate gas pipelines.

FERC’s approval of gas infrastructure has generated much debate in recent years. While some claim that additional infrastructure is needed to keep up with increases in gas production and use, others are concerned about the potential for overbuilding, particularly given the need to decarbonize the energy system to mitigate climate change. Many argue that expanding natural gas infrastructure will make decarbonization more difficult for a range of reasons, including owners not wanting to lose their investment value and have their assets become stranded.

FERC has, to date, paid relatively little attention to the climate impacts of its infrastructure decisions. Consider, for example, its approach to determining whether new gas pipelines are in the public interest. As part of that determination, FERC considers the need for the pipeline, based primarily or solely on whether the additional capacity it creates has been contracted for. Regulatory and industry experts have demonstrated to FERC that, when viewed in isolation, these contracts are unreliable indicators of whether additional capacity is actually needed, especially given regional build-out or overbuild. These arguments have been detailed in Amicus briefs to the D.C. Circuit, as well as in filings before FERC. And as we have previously argued to FERC, most contracts have terms of just five to fifteen years and thus provide little indication of whether a pipeline will be needed over its full useful life of fifty years or more. That will depend, in part, on government and private sector responses to climate change. Despite this, FERC does not consider the potential impact of existing or proposed new government policies, programs, or regulations to mitigate climate change, nor market shifts prompted by climate concerns.

FERC also largely ignores the climate impacts of gas pipeline construction and operation. Before approving any new pipeline, FERC conducts an environmental review under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), and purportedly considers the results of that review when determining whether the pipeline is in the public interest. As part of its environmental review, FERC typically considers the GHG emissions resulting directly from pipeline construction and operation (e.g., due to natural gas leaks). Notably, however, it rarely considers the GHG emissions associated with upstream production and downstream use of natural gas transported by the pipeline.

A 2019 study by the Sabin Center found that, of the 111 environmental reviews conducted by FERC from 2014 to 2018, nearly thirty-percent included no mention of upstream or downstream GHG emissions. Even when mentioned, upstream and downstream emissions typically received little attention, with FERC generally not even quantifying the extent of such emissions. And in none of the cases did FERC consider the climate consequences of the emissions. While other agencies use the social cost of carbon to estimate the damage associated with emissions, FERC has refused to do so because (in its view) the “tool has methodological limitations” that undermine its usefulness. This enables FERC to claim that it cannot determine whether the emissions associated with a particular project are significant, a position that has been criticized by Chairman Glick, who recently wrote on dissent to a pipeline approval: FERC’s “analysis of the Project’s contribution to climate change is shoddy and its conclusion that the Project will not have significant environmental impacts is illogical. After all, the Commission itself acknowledges that GHG emissions contribute to climate change, but refuses to consider whether the Project’s contribution [to emissions] might be significant before proclaiming that the Project will have no significant environmental effects.”

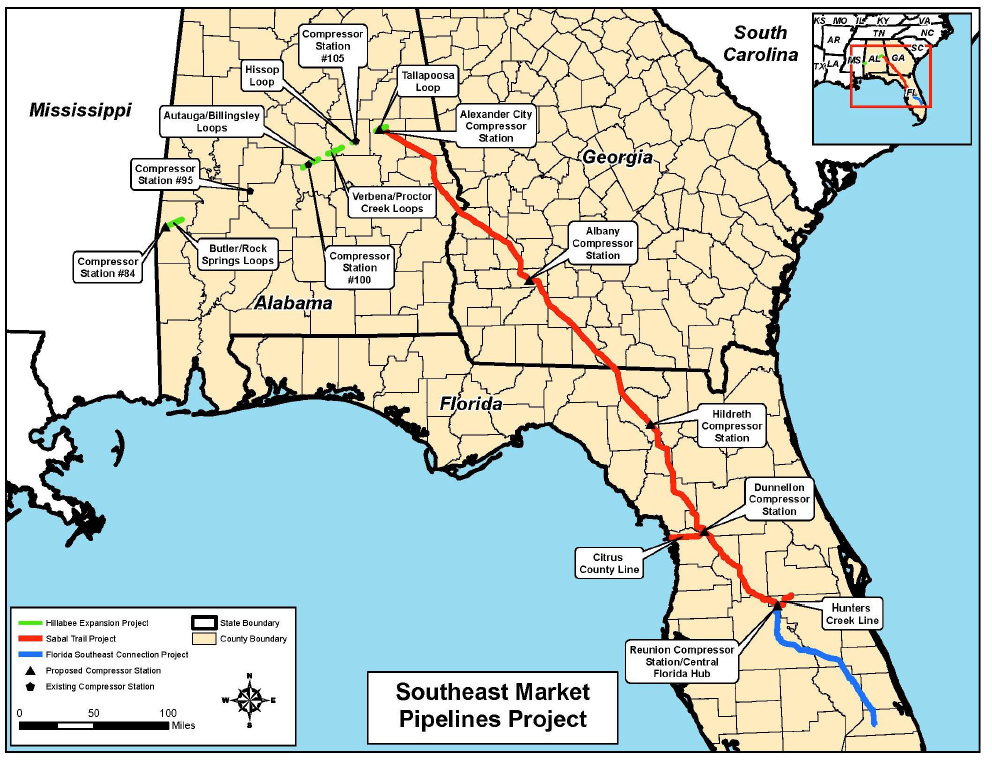

FERC’s failure to consider upstream and downstream GHG emissions has generated significant controversy. Our colleagues Michael Burger and Jessica Wentz, as well as others, have argued that FERC and others are legally obligated to consider upstream and downstream greenhouse gas emissions under NEPA (see here and here). Environmental and landowner groups have taken that argument to the courts, challenging a number of FERC pipeline approvals. They had a notable success in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in Sierra Club v. FERC. That case concerned FERC’s approval of three pipelines intended to deliver gas to power plants in Florida. FERC did not consider the downstream GHG emissions associated with combustion of the gas at the plants in its NEPA review because, it argued, those emissions were not a reasonably foreseeable effect its decision to approve the pipelines. That argument was rejected by the court which concluded that FERC’s decision was a “legally relevant cause” of the downstream emissions. In the court’s view, it was “not just reasonably foreseeable” that gas delivered to the power plants would be burned, that was “the project’s entire purpose.”

During the Trump administration, a majority of FERC commissioners took a narrow view of the Sierra Club ruling, arguing that it only requires consideration of downstream GHG emissions where FERC has “meaningful information” about how the gas transported via a proposed pipeline will be used. As discussed in a previous blog, the Trump administration’s amendments to NEPA’s implementing regulations, finalized in 2020, made it easier for FERC and other agencies to ignore upstream and downstream emissions. Among other things, the amended regulations restrict NEPA analysis to effects that have a “reasonably close causal relationship” to a proposed project, and give agencies discretion to ignore effects that do not occur at the same time or place as the project.

While the courts have not ruled on the legality of FERC’s approach, in Birckhead v. FERC, the D.C. Circuit indicated (in obiter) that it was “troubled” by the failure to consider upstream and downstream GHG emissions. So too is Chairman Glick, who has said that it “violates NEPA’s requirement that federal agencies take ‘a hard look at [the] environmental consequences’ of their decisions.”

Even if one accepts (which we do not) that FERC could ignore upstream and downstream GHG emissions under NEPA, it has a separate obligation to consider them under the NGA, which requires it to ensure that any new pipeline “is or will be required by the public convenience and necessity.” The courts, and FERC itself, have consistently recognized that environmental factors must be considered when determining public convenience and necessity. FERC’s predecessor – the Federal Power Commission – once described downstream environmental impacts as “one of the most important factors” to be considered and the courts have indicated that they should be given “great weight” (see our previous report here for a more detailed discussion). Chairman Glick clearly agrees, recently writing that FERC “must carefully consider [each] Project’s contribution to climate change, both in order to fulfil NEPA’s requirements and to determine whether the Project is required by the public convenience and necessity.”

Now that he has been appointed Chairman, Glick can and likely will resurrect a review of FERC’s pipeline certification process, which began under former Chairman McIntyre in 2017, but has since languished. There are signs that FERC’s two newest Commissioners – Democrat Allison Clements and Republican Mark Christie – might join Glick in supporting changes to the current process. In her confirmation hearing, Commissioner Clements acknowledged that “the issue of climate change is sometimes relevant to [FERC’s] exercise of its authority” and that GHG emissions “should be included in [the] NEPA analysis” of pipeline projects, “in at least some circumstances.” Commissioner Christie was more evasive, but did say that FERC should base its decisions on the “best available” and “most complete” information. A former state energy regulator, Commissioner Christie has also said that he understands the importance of honoring state energy policies, many of which are now focused on reducing GHG emissions. Another Republican Commissioner – Neil Chatterjee – has also said that he supports exploring opportunities for FERC to work with states on climate change. Integrating climate considerations into FERC’s pipeline decisions would be a good place to start. And given Commissioner Glick’s commitment to assessing environmental justice impacts of fossil fuel infrastructure siting, and his acknowledgment that such adverse impacts are squarely part of FERC’s obligation to determine whether a project is in the public interest, we could see the existing policy shifting to weigh these impacts head on, rather than “shrug[ging] them off.”

With the support of Commissioners Clements, Christie, and Chatterjee, Chairman Glick could oversee a fundamental reshaping of FERC’s approach to fossil fuel infrastructure approvals, with greater focus on climate impacts. Even if Chairman Glick does not currently have the support he needs, he’s likely to get it soon because Commissioner Chatterjee’s term is expiring on June 30, at which point President Biden can replace him. If the President’s recent appointments to other agencies are anything to go by, he is likely to choose someone who recognizes the imminent threat posed by climate change, and supports action to address it. That could also lead to a major shift in FERC decision-making.

The Biden administration can and should support efforts by FERC and other decision makers to better account for climate impacts. The administration has already taken an important first step by re-establishing the Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases and directing it to publish an updated social cost of carbon that agencies can “use when monetizing the value of changes in [GHG] emissions resulting from regulations and other relevant agency actions.” Next, the administration should begin the process of revising the NEPA implementing regulations to require agencies to consider reasonably foreseeable climate impacts, including upstream and downstream GHG emissions. Absent such consideration, agencies may continue to ignore the single largest existential threat of our time. If agencies fail to consider foreseeable climate harms, they certainly cannot weigh them to determine whether any particular project serves the public interest. Perhaps some fossil fuel projects can survive this critical analysis. But, if agencies don’t ask the question, the public will certainly never get a reasoned answer.

This is test biographical description.