By Bernard E. Harcourt

I greatly appreciate the emphasis, in the insightful comments and articles by Nancy Fraser, Richard Brooks, and Kendall Thomas, on the issue of political economy as a source of truth-making, on the question of neoliberalism as a regime of truth, and more specifically on the central idea of the market as the basis for the validation of political action.

Now I realize that in our discussion, and in Kendall Thomas’s comments especially, we may want to go further than that to explore neoliberalism in terms of its concrete practices, material distributions, and fantasies… or what Kendall calls “fantastications.”

I would note that Foucault himself was aware of those alternative avenues and possible critiques of his reading, and consciously deduced not to go down those paths. On page 130 of The Birth of Biopolitics, Foucault discusses this “third response” to his approach, namely that “from a political point of view neo-liberalism is no more than a cover for a generalized administrative intervention by the state which Is all the more profound for being insidious and hidden beneath the appearances of a neo-liberalism.” In the face of that critique, Foucault develops an approach that tries to “grasp” the different strands of neoliberalism (German, French, American) “in their singularity” from within their logic of governing.

Foucault’s method, in this sense, is more of an imminent analysis than we might adopt; and if I had to identify the single most important contribution of Foucault’s method in these 1979 lectures it is precisely the epistemological dimension of the market in relation to civil society and the state. This is captured precisely in the passage on page 32 where Foucault states that:

The market must be that which reveals something like a truth […] [I]nasmuch as prices are determined in accordance with the natural mechanisms of the market, they constitute a standard of truth which enables us to discern which governmental practices are correct and which are erroneous. […] The market constitutes a site of veridiction. (BB, p. 32).

This is the heart of Foucault’s intervention on neoliberalism, which continues his nominalist method—i.e. to explore the real effects of the category of the market—and it places the analysis squarely, as Foucault suggests in these lectures (p. 34-36), in line with his nominalist critique of madness, of delinquency, and of sexuality.

It is also what grounds his truly insightful analysis of contemporary German governmentality—prescient, because it almost feels as if his discussion on p. 84 about “economic growth producing sovereignty” (with which I concluded my introductory post) could have been written today in the midst of the Greek debt crisis and the contemporary place of Germany in the Euro zone.

This reading also places the 1979 lectures in continuity with the “history of regimes of truth” that was his project at the Collège de France and that had gone, first, through juridical forms, then historical forms, and is now on political-economic forms: we are here on the question of “Truth and Economic Form.”

It is in this sense that I think Nancy Fraser and Rick Brooks’s emphasis on the relation between economy and society – and especially on the notion of civil society – is so important and insightful. And should form one axis of our conversation: the question of how to understand the conceptualization of civil society and its relation to the state and the economy in the logics of liberal governmentality.

As a footnote here, I was particularly taken by Nancy Fraser’s reinterpretation of Foucault’s contention that “socialism” lacks a governmentality. I find Nancy’s correction or reorientation of that claim truly novel and interesting. I have long struggled to understand that passage. And at a high theoretical level, I agree with Nancy’s reinterpretation.

But I also did want to throw in a more political reading—given that we are in an election cycle here and in France today. I had always read this passage not at a high theoretical level, but rather more at an engaged, partisan, political level. I had always sensed that Foucault was poking the contemporary socialist party at the time, in 1979.

And from that perspective, I would say, it may not have been entirely off target, and might be even more appropriate again today. With a socialist government in France today that has basically found little better to do in the current crisis following the November 13th attacks in Paris to promote (1) a measure called “la déchéance de nationality” that would strip citizenship from dual-nationals convicted of high crimes, a measure that was the pet project of the Front National and the right-wing parties; and (2) the constitutionalization of the perfectly legal (just upheld by the Conseil constitutionnel) statute on the “état d’urgence.”

In other words, rather than governing, by default the socialist government is simply borrowing the strategies and tactics of the right—and thereby ensuring their passage. If the right were in power, it’s not clear that they would have sufficient votes to pass these measures; but because the socialist government is so démunit, impoverished in its own governmental rationale, it seems to have found better to do than to put in place the punitive strategies of the right. In many ways, we saw exactly the same thing in this country with President Bill Clinton on penal law measures—with Clinton’s passage of the federal death penalty and the AEDPA and other repressive measures that had a devastating toll on African American and Hispanic communities in this country and fueled massive overincarceration.

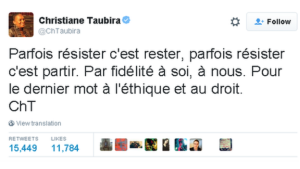

And this leads me to believe that Foucault may have had something insightful to say in his quip that socialism or the center left lacks a governing rationality. It’s enough, I might add, to make a true minister of justice resign. And for that, I must admit, I greatly respect Madame Christiane Taubira. As you may know, she resigned from Hollande’s administration, and left with a strong statement, a powerful message—an act of truth-telling:

Let me turn then to the second and third dimensions for our conversation, focused on two other critiques of neoliberalism.

Rick Brooks underscores, very insightfully I believe, one of the main critiques of American neoliberalism that Foucault began to sketch in these lectures. It is his critique of the disparate investment decisions that follow from a theory of human capital. It is the problem of how to invest in human capital in society when the only guiding norm is efficiency.

This raises the question of how to build on Foucault’s critiques of neoliberalism. There are, as I can read it, three central critiques of neoliberalism in these 1979 lectures, and I would want to ask our speakers about the other two.

- The first critique is the one that Rick Brooks identifies. Let me just locate it for you quickly in the text. It is from the lecture of March 14, 1979, and is in the two last paragraphs on pages 232 and 233. There, Foucault argues that the danger (“menace“) of the theory of human capital is that it orients all our social, cultural, educational, and economic policies towards selective & discriminate investment decisions regarding human capital, based on criterion of effectiveness that may have detrimental effects on specific communities—and I am thinking here for instance of African American and Hispanic communities that have been devastated by our collective investment in prisons. Foucault lectures:

On the basis of this theoretical and historical analysis we can thus pick out the principles of a policy of growth which will no longer be simply indexed to the problem of the material investment of physical capital, on the one hand, and ofthe number of workers, [on the other], but a policy of growth focused precisely on one of the things that the West can modify most easily, and that is the form of investment in human capital. And in fact we are seeing the economic policies of all the developed countries, but also their social policies, as well as their cultural and educational policies, being orientated in these terms. […] So, we are invited to take up a schema of historical analysis, as well as a programming of policies of economic development, which could be orientated, and which are in actual fact orientated, towards these new paths [i.e. investments in human capital]. […] [T]he political connotations owe their seriousness, their density, or, if you like, their coefficient of threat to the very effectiveness of the analysis and programming of the processes I am talking about.

There are, however, two other critiques in these lectures. I would like to put them as well on the table for discussion, perhaps to ask our seminar participants how or whether to incorporate them in their perspectives.

- The second is from the lecture of March 21, 1979, and it too is developed in the final two paragraphs of that lecture on pages 259-260: The critique here is that there is a too thin notion of the subject as homo economics, and that this thinness produces very flat options for governmentality—nothing but shallow environmental and behavioral tweaks geared toward nudging behavior. This second critique is the one that François Ewald refers to at the end of our first Becker-Ewald seminar at the University of Chicago in 2012, when Ewald argues that “the resulting conception of governmentality [in neoliberalism] is not rich.” (Carceral Notebooks Vol. 7, page 29). On pages 259-260 of the lectures, Foucault states in the context of punishment:

penal action must act on the interplay of gains and losses or, in other words, on the environment; we must act on the market milieu in which the individual makes his supply of crime and encounters a positive or negative demand. This raises the problem, which I will talk about next week, of the new techniques of environmental technology or environmental psychology which I think are linked to neo-liberalism in the United States.

[… This is a society in which] action is brought to bear on the rules of the game rather than on the players, and finally in which there is an environmental type of intervention instead of the internal subjugation of individuals.

Now, this may be attractive in some ways, especially in light of the excesses of the late 19th century penology, with all its biological, hereditary, anthropological, and sociological theories of degeneracy, abnormality, anomie, and phrenology which led to such repressive penal strategies including sterilization and other extreme forms of discipline. But nevertheless, this neoliberal alternative has its own problems of thinness that treats humans as mere pavlovian dogs.

It is important to remember here that critique is not about not being governed. It is about not being governed in this way (see “What Is Critique?). And here, this way is a thin and pavlovian approach that raises its own problems.

Note that, contrary to the suggestion in n. 36 and 37, this line of argument is reelaborated on page 270 of the next lecture of March 28, 1979 with the discussion of “the new behavioral techniques, which are currently in fashion in the United States.”

- The third critique is from the lecture of March 28, 1979, and can be located on pages 282-283: This is the critique that the very ideal of a limited government is baked into the cake because of the underlying theory of the subject in the rational actor model. In other words, the political outcomes are assumed from the get-go and inscribed into the notion of the rational, self-interested subject that founds the very approach. The original theory of the self-interested and self-knowing subject simply disqualifies the knowledge of the political sovereign. In other words, if we begin with a subject who alone is the knowing subject, there is little doubt that the political body will ultimately be disqualified. Foucault explains this here:

Economic rationality is not only surrounded by, but founded on the unknowability of the totality of the process. Homo economicus is the one island of rationality possible within an economic process whose uncontrollable nature does not challenge, but instead founds the rationality of the atomistic behavior of homo economicus. Thus the economic world is naturally opaque and naturally non-totalizable. […] Liberalism acquired its modern shape precisely with the formulation of this essential incompatibility between the non-totalizable multiplicity of economic subjects of interest and the totalizing unity of the juridical sovereign.

[…] Homo economics … tells the sovereign: You must not. But why must he not? You must not because you cannot. And you cannot in the sense that “you are powerless.” And why are you powerless, why can’t you? You cannot because you do not know, and you do not know because you cannot know.

[…] the basic function or role of the theory of the invisible hand is to disqualify the political sovereign.

This third critique can also be discerned in two other places. First on page 271, when Foucault begins the discussion, rhetorically:

Is homo economicus […] not already a certain type of subject who precisely enabled an art of government to be determined according to the principle of economy, both in the sense of political economy and in the sense of the restriction, self-limitation, and frugality of government?

Second, on page 292 on April 4, 1979, in the last lecture, where Foucault is discussing the fact that “Homo economicus strips the sovereign of power inasmuch as he reveals an essential, fundamental, and major incapacity of the sovereign, that is to say, an inability to master the totality of the economic field. The sovereign cannot fail to be blind vis-a-vis the economic domain or field as a whole.”

I believe that this third critique was validated or demonstrated in our second Ewald-Becker seminar at the University of Chicago in 2013 when Becker spontaneously exclaimed that “I believe there’s a lot of risk of government overregulating society with too many laws, and that’s why I’ve always been a small government person.” (Carceral Notebooks, Vol. 9, p. 32). Becker would return to this question and explain on pages 37-38:

It comes from a belief that the government usually makes things worse, rather than making them better, for the bulk of the population. It’s an analysis—it may be a wrong analysis, but that’s the analysis. […] When I say I’m a small government person, I am making the judgment that whatever the imperfection when the private sector operates, the effects are worse when I see the government operating. Now, other people may say that the evidence for that is not so clear, that in other sectors it is different. I recognize that. But that is what it would be based on. (Carceral Notebooks, Vol. 9, p. 37-38)

That exchange, to my mind, simply instantiates the third critique: there is an epistemological assumption about homo economicus that produces the political outcome favoring [purportedly] a small government. I add “purportedly,” of course, because the small government is joined at the hip by a police state constructed around the market to give the market the illusion of natural order.

In any event, the notion of subjectivity assumed by the rational actor model is a key question, a foundational issue in the field of penalty. And I would ask our discussion leaders, then, what to make of those two other critiques of neoliberalism. But let me turn it back to Jesús Velasco to moderate the conversation, with great thanks to Nancy Fraser, Rick Brooks, and Kendall Thomas.