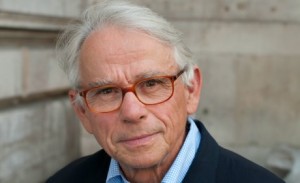

By François Ewald

Transcribed and edited by Raphaëlle Jean Burns; reviewed and approved by François Ewald

[Editors’ Note: This is an edited transcription of François Ewald’s talk at Hunter College CUNY on Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 2:30-4:00 pm Room 204 Roosevelt House, Hunter College. The talk was titled “Foucault’s Neoliberalism: European and American Perspectives.” The talk was sponsored and moderated by Professor Sanford Schram of Hunter College, CUNY. The audio version can he listened to here]

[To read or watch François Ewald’s debate with Gary Becker regarding Foucault’s lectures on Becker and Neoliberalism in The Birth of Biopolitics, please read here or watch here on American Neoliberalism (lecture of March 14, 1979) and read here or watch here on Crime & Punishment (lecture of March 21, 1979)]

Foucault & Neoliberalism

François Ewald

I will try to respond to your questions regarding Foucault’s relationship to neoliberalism from my own point of view and by way of a series of remarks.

My first remark concerns my astonishment at this identification between Foucault and liberalism. For me this question makes absolutely no sense. I remember these lectures [Birth of Biopolitics], as I was naturally in the room at the Collège de France when Foucault delivered them, and there were absolutely no indications that he shared any of the ideas of Gary Becker or anyone else from that school of thought.

The real question, in fact, is not the connection between Foucault and neoliberalism, but why some people wish to pose this question now. Perhaps this is a new way to disqualify Foucault’s thought, this time from the angle of neoliberalism. But—and this is a hypothesis—I think the problem is more profound, and that this critique is not exactly about neoliberalism.

To prepare for this talk and this seminar, I visited the Bibliothèque nationale de France last week to read Foucault’s journals (“cahiers”) from the time of these lectures. In them (although this is not directly related to our topic) Foucault writes about the fight against “les bons sentiments théoriques,” that is to say warm or normative, let’s say conventional, feelings regarding theory and its objects. He writes: “à propos de la répression qu’on déteste, la société civile qu’on aime, l’état qu’on deteste, la délinquance qu’on aime” (about repression, we don’t like repression, civil society, we like civil society, the state, we don’t like the state, delinquency, we like delinquency). Foucault prefers to be free of this kind of normative thinking, these “bons sentiments”: repression is bad, madness is beautiful, etc. These kinds of judgments are completely uninteresting for Foucault. He searched to free himself of them. That is what is written in these journals.

Connecting these lines with the accusations about Foucault’s complicity with neoliberalism, we should ask ourselves how to read his work. Indeed, one could ask the same question about Foucault on Christianity. He delivered a lot of lectures on the Fathers of the Church. Does that mean that Foucault was, at the time, a priest? In the lessons of 1977-78, Foucault spoke about raison d’état (Reason of State) in exactly the same terms as liberalism. [Does that mean he was in favor of raison d’état?]

Foucault made a distinction between German ordo-liberalism and American neo-liberalism. Today, when we speak of neoliberalism, we refer more often to the American strand of liberalism than the German one. But it is the German one that is for these times, of these times. In Europe we make a very strong distinction between these two forms of liberalism: German liberalism, which goes very well with the welfare state, with protection, with the social safety net (“securité”) etc. and is in this way very different from American neoliberalism.

These lectures raise the question of the nature of Foucault’s philosophical thought. Naturally we think that his thought favored that of which he spoke, namely the topic of liberalism. I disagree. In his speech one has to distinguish the “énoncé” (the topic, that about which he spoke) and on the other hand the reasons why he spoke about it: “énonciation.” Foucault’s philosophy is to be found not in his énoncé, but in his énonciation, and this is more difficult.

We cannot simply identify the topic about which Foucault wrote with what he was thinking at the time. What is true, however, is that when he gave these lessons, Foucault had a political project. He was not a liberal, but his was a very strong political project in the context of the end of the 1970s not only in France, but in Europe. One can find a lot of indications in these lessons of Foucault’s will to propose, to reinvent, a new form of political philosophy. That is clear. And this is what is of most interest: this political project at this particular time. That was my first remark.

My second remark: Naturally then, we need to remember what the context was: both the context for Foucault and the general context of the late 1970s. When reading these lessons, one can sense that Foucault was personally implicated; there is some joy there, following the progress of his work. We have a first sequence from 1971 to 1976, in which Foucault proposes a program about daily life, about the transformations of society and the revolution brought about by the politicization of daily life. That was his program at the time. When Bernard Harcourt and I worked on the Situation de Cours for the lessons from that period, we found that, in the early 1970s, Foucault thought that this program could change society, could make it revolutionary by an intervention in local questions on daily life. We could also see that Foucault was inclined to think that this program would be effective very quickly. In May 1976, he made some observations about norms, but nothing happened. That was, however, during the time of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s presidency in France, that is to say not the brightest of times.

I think that although we can make these observations about Foucault’s first political project, we find at the same time, for example in The Will to Know, a critique: both a critique of himself and a critique of the political category of “May 68.” That is to say, we find a critique of the question of repression and of the topic of liberation, which was crucial to the “May 68” way of thinking. At the end of The Will to Know, Foucault provides a radical critique of the idea that there is, that we have, something to liberate, to release. And exactly at the same time, Foucault said that political philosophy was always dictated by a connection with the topic of revolution. He says in an interview with Bernard Henri-Lévy, and this is an important point, that the revolution is no longer desired and that we have to invent, to make politics outside of this framework of the revolution, in other words, that we have to find a completely new manner of making and dealing with politics.

If one deals with Foucault on liberalism, if one deals with these lessons, I think we can say that they are the step beyond this critique. We find in them Foucault’s new proposition on the question of government and governmentality. This proposition is not expressed at the beginning of these lessons, however, but only after three to four lessons. That is, when he finds this term “government” and says “that is what I’m looking for.”

Exactly as when in his last lecture series he discovers the term parrhesia and finally came to be at peace with himself. That was an important moment for him, when he could look back at his own life and ask the question “What is a philosophical life? ” It was a moment when he could say, in retrospect, that a philosophical life was to follow the way of parrhesia and that was what he did: what he tried to do was to be a parrhesiast. And, indeed, he was. I regret that we could not edit in the same volume the two final lessons from the Collège de France, because, at least that is my view, they deal with the same subject: they are about Foucault himself, they are the biography he gave of himself. On the last two days, what we could hear in the lecture room at the Collège de France, was Foucault speaking about himself.

At the end of the 1970s, we enter into a new world for political philosophy and he had to invent something new to address this question. And for that, Foucault turned to the concept of governmentality. That was my second remark.

My third remark: In this program or this project, the main question is then to rethink political philosophy, and Foucault begins with the question of population: population comes from biopower. The question of population provides a path to governmentality, and when Foucault arrives at this notion of governmentality he realizes that it is his topic. He says: “I have to write the story of the notion of government.”

So the project at this time is about government: the question of liberalism is not present at the beginning, it comes only the year after. If we want to respond to Daniel Zamora, then we can say that when Foucault builds this new project he isn’t thinking about liberalism. He thinks of pastoral power, of raison d’État, but not of liberalism, which comes only later. I think we can say that the question of liberal governmentality was not at the beginning of this project but that he meets the question of liberalism when, at the end of the first year, he encounters the question of the transformation of raison d’État (of the Polizeiwissenschaft) during the 18th century and alongside the question of population which remains omnipresent throughout these lessons.

Here we can understand Foucault’s resistance, and the resistance against Foucault. In these lessons there are many pages in which Foucault spoke about the “state”, and he spoke about this idea to say that the mainstream political and philosophical problem is a question of state, and that his project was to be free of this very question, the question of state.

Perhaps we have to remember that at this time, the main question was the question of the totalitarian state. This notion of the totalitarian state is absolutely not a Foucauldian one. Or at least I don’t think it is—maybe here, in this talk, it is difficult to say. That is, we find a certain amount of critique for example of Hannah Arendt. I never spoke with Foucault about Hannah Arendt. He did not speak about her much, but I think this lesson was written and given in a comparison with this tradition of totalitarianism, with this main corpus about the question of totalitarianism and the question of the state.

In these lectures, Foucault denounces this obsession, which he calls state “focal” or “focused,” according to which all the “ideas” come from “state”. This critique returns again and again in these lessons. For Foucault, the state is a problem, and we know that this is an old question for Foucault. We spoke about that in yesterday’s seminar [Foucault 2/13], when we mentioned Foucault’s idea that—in different kinds of state, totalitarian or liberal—we can effectively observe different kinds of state but the same kinds of power relationships. We can observe the same kind of disciplinary society in France as in the USSR, it was only a question of quantity, of gravity that differentiated “disciplinarisation” in the USSR from “disciplinarisation” in Europe. It is a form of critique of Marxism to say that one cannot differentiate between these kinds of state where in fact the reality of power is the same, and that what we have to fight is the power—this kind of power—and not the state.

So we can see that what is at stake for Foucault in the notion of governmentality is to be free of the question of state and to break away from this immense corpus about the state, the totalitarian state and so on. Foucault was very, how shall I say, “arched” (“tendu”) in this way. And when you read these lessons, that is very clear.

So, this is the context. And in this context, Foucault finds a new category, a new field. He finds the possibility to elaborate a new form of political philosophy thanks to this question of governmentality. This new question opens onto a whole new field and creates the possibility for a new corpus in the field of political philosophy. No more Machiavelli, no more Hobbes, but a lot of other things: pastoral power, Reason of State, Giovanni Botero and so on. And also liberal thought.

That is the field of inquiry that is opened up by this manner of reconsidering political philosophy at this time in Foucault’s research. It provides the possibility for discovering a lot of new authors, an absolutely new corpus, and the question of liberalism was only one of the questions “liberated” by this vision.

But what does Foucault do with liberalism? First, as we have seen, he doesn’t begin with the question of liberalism, he only begins to raise the question at the end of Security, Territory, Population and at the beginning of Birth of Biopolitics. What he observes is that, during the 18th century, there is a big critique of the administrative state grounded in the idea that the government has to follow the natural evolution of the society, of the population, of its interests. But this discourse, at this time in Foucault’s work, is not known to him as liberalism, but as political economy. Thus, the first apparition of the topic is not strictly speaking the question of liberalism but that of political economy. It is this kind of political discourse including the topic of the market in the 18th century which interests Foucault here.

His next step will be to propose that we can call this kind of governmentality—or this kind of critique of raison d’État—liberalism. But at this time he wrote “liberalism” in scare quotes, because he is not sure whether the term was appropriate. That is another important remark. It is at this time that he discovers the question of liberalism and it really is a discovery, not a conviction. He is testing the term, he does not know whether it is a good one or not, and his description of liberalism is absolutely not a liberal one.

We have to remember that Foucault makes an important distinction: liberalism, or this kind of governmentality, is a way by means of which to produce liberty and also to produce security and control. It is absolutely not laissez-faire. And liberty, he explains, is not something to be observed like a quality or a property of man, no, liberty is what this kind of government has to produce to govern the people: “I make you free, because if you are free I can better govern you.” Perhaps you think that this is a very liberal sentence, but that is not so evident to me.

In certain parts of these lessons he recognizes that first, if we have to provide a description, an analysis of contemporary political parties, we have to deal with the question of liberalism. He says that liberalism and liberty are concepts that come to us from Germany. The documents in the Bibiliothèque nationale de France, if you ever have a chance to read them, reveal that Foucault was in fact very interested in what happened to Germany after the Second World War. This is very important, because this has to do with the scheme of release from a totalitarian state, it concerns the question of how it was possible for Germany to be free from Nazism and what path was followed. He was certainly also very interested in the manner in which people like Friedrich Hayek—at this time, at the end of the Second World War—critiqued the welfare state, the question of planning and so on. And so, came the hypothesis: is there a similarity between the question of how to exit a totalitarian state like the Soviet Union, which was a question for us in the 1970s, and the example, the case, of the exit from Nazism in Germany. This question of “ordoliberalism” is a very important one.

Some further remarks: I think that there are many reasons behind Foucault’s interest in the question of liberalism. Very quickly, the first one that I already spoke about, and that is the question of what was happening at the time in Foucault’s contemporary. This leads to the question of Germany again, not Germany after the Second World War however, but the Germany of Helmut Schmidt.

When, at the end of these lessons, Foucault says “I will spend some time speaking of liberalism”, he says this because it is a contemporary question. This sentence corresponds exactly to what Foucault gave at this time as a program for his own philosophy, the question of Aufklärung, the question of actuality. And in these lessons Foucault is practicing what he spoke about for example in the conference he gave at the French Philosophical Society around the question “What Is Critique?” Critique, he says, is to have a certain kind of relationship with one’s present, and here, in the lessons, we have an example of the putting into practice of this program.

I think that is the first thing. But perhaps I am not sufficiently clear: I spoke at the beginning of this talk of this crisis in Foucault’s politico-philosophical vision in 1976. What is very important to me about this conference is that Foucault formulates another political program, with the question of critique and Aufklärung. The first project is not exactly abandoned, but he formulates a new one with the question of critique and this relationship to what is contemporary with philosophy, like journalism and so on.

But the question for Foucault, what is at stake for him, in this kind of critique is not so much to understand the relationship (although this is not exactly the word that Foucault uses) between knowledge and power, that is old, but between veridiction regimes and the rationalisation of power. What is at stake for him is the connection, the cross, between the politics of truth and forms of governmentality. When one reads his lessons, we find that he was very interested in intellectuals, “ordoliberals” who were intellectuals, absolutely and only intellectuals, that is to say professors during the middle of the 20th century with no power, no position of influence, that however produced forms of knowledge which have political effects in terms of liberty.

If you are a specific intellectual (“intellectuel spécifique”), if you define your job as intellectually specific, what can it mean to have a certain kind of connection with a certain kind of power, and to use one’s knowledge to transform power relationships in the direction of liberty? Foucault’s encounter with this literature is certainly very interesting, and provides an opportunity to reflect on this new program he was proposing. I don’t say that he agrees, that for these reasons he becomes liberal, no, but if we have to reflect on this connection between veridiction and governmentality then this question of the connection between order in liberal economy and the practice of government is a case to study. That is not to become liberal, it is to observe a very interesting case. That is, for me, one of the reasons for his interest in the question of liberalism.

We need to remember that we are in a post-revolutionary moment for Foucault at this time. In France there were discussions at the time concerning the possibility that François Mitterrand could be elected with the Communist party in France. These lessons are very interesting in this perspective, and indeed we find pages dedicated to the question of socialism in which Foucault says “there is no socialist governmentality,” and this is a radical critique of the socialists. What we need, he says, is to build a new kind of governmentality, but socialism is not a solution, is not a response, because there is not a socialist governmentality.

My last remarks: At the end of Birth of Biopolitic we do not find Gary Becker. That means that the discussion of American liberalism is not the end of the story. At the end of these lessons, Foucault comes again to the question of population and civil society, and he says that the main question is the question of the connection between civil society and state. The final argument in these lessons is not focused on liberalism. Liberalism is only an example, only a case, but not the whole of the reflection. After this, Foucault doesn’t discuss these kinds of questions again. He said: “qu’est ce que la politique finalement, sinon à la fois le jeu de ces différents arts de gouverner, avec leurs différents indexes, et le débat que ces différents arts de gouverner suscitent” (What is politics in the end if not both these different arts of governing with their different indexes or methods, and the debates that these different arts of governing trigger.) So the last word here is not a liberal confession, but that liberalism is only one art of governing and that there are other kinds of arts of governing. And what is politics? It is the debate between different kinds of arts of governing.

I don’t know if these remarks will be interesting for you, but that is perhaps all I can say. These are short remarks, and that is always difficult, but if I had to speak about Foucault and neoliberalism that would, in any case, be my way.