By Jesús R. Velasco

“Je veux parler de la grande, tendre et chaleureuse franc-maçonnerie de l’érudition inutile.” (Il faut defendre la société, 6). Now, this useless erudition is not the “feverish laziness” of those who feel part of a secret society in search of those books that, just off the press, became part of the opacity of the archives. Foucault would like to read something else, what he calls the “savoirs asujettis”, “a particular knowledge, a knowledge that is local, regional, or differential, incapable of unanimity and which derives its power solely from the fact that it is different from all the knowledges that surround it” (8). It is this kind of discontinuous, haphazard production of knowledge, from below, that Foucault was after. He wanted to pursue, “l’insurrection des savoirs asujettis”, and he suggested to do it by focusing on those knowledges, that have been “ensevelis, masqués dans des cohérences fonctionnelles ou dans des systématisations formelles” (8).

“Concrètement –he says—si vous voulez, ce n’est certainement pas une sémiologie de la vie asilaire, ce n’est pas non plus une sociologie de la délinquance, mais bel et bien l’apparition de contenus historiques qui a permis de faire, aussi bien de l’asile que de la prison, la critique effective. Et tout simplement parce que seuls les contenus historiques peuvent permettre de retrouver le clivage des affrontements et des luttes que les aménagements fonctionnels ou les organisations systématiques ont pour but, justement, de masquer. Donc, les ‘savoirs asujettis’ ce sont ces blocs de savoirs historiques qui étaient présents et masqués à l’intérieur des ensembles fonctionnels et systématiques, et que la critique a pu faire réapparaître par les moyens, bien entendu, de l’érudition” (8). It seems that “réapparition”, here (what Macey translates as “revelation”) is in contrary opposition to the idea of “reconstruction” that underwrote philological research and traditional erudition. Foucault is not interested in the “reconstruction” of something as it was, but in summoning up from the past those subjected knowledges (or subjected pieces of knowledge) in order to proceed to an effective critique of contemporary issues and contemporary problems. His entrance into the archives is not that of the “feverish laziness” of the researcher (an image that most probably he borrowed from Nietzsche’s second Untimely meditation, when he refers to “der verwöhnte Müßiggänger” in the garden of knowledge). He wants to be the other kind of archivist Deleuze talks about at the beginning of his Foucault, a new archivist who named himself to the position. “The new archivist proclaims that henceforth he will deal only with statements. He will not concern himself with what previous archivists have treated in a thousand different ways: propositions and phrases. He will ignore both the vertical hierarchy of propositions which are stacked on top of one another, and the horizontal relationship established between phrases in which each seems to respond to another. Instead he will remain mobile, skimming along in a kind of diagonal line that allows him to read what could not be apprehended before, namely statements” (Deleuze, Foucault 2). Those rare statements, harvested in uncommon, difficult circumstances (the alphabetical order, Deleuze suggests, on top of French typewriters, that has been recently exploited by Éric Chevillard), are what the archivist is after.

Because of that, Foucault’s walks in the archive are equally rich and a-systematic. And this is why they need to be again at our disposition, so that we can understand –or at least question—the kind of statement that the very entrance in the archive produces.

We are simply giving access to some of those titles that Foucault used in Sécurité, Population, Territoire. Those are also titles that he was discussing with some of his closer students, in the parallel seminar they conducted (including the one studying the variole), and that lead to the writing of dissertations and other academic publications. One of those students was the very editor of STP, Michel Senellart, whose work on the raison d’État (1989, 1992), and his book on Les Arts de gouverner. Du regimen medieval au concept de gouvernement (Paris: Seuil, 1995), draw considerably on Foucault’s lines of questioning from STP to Le Courage de la vérité, especially.

This list is very far from complete. It only contains a very small set of references, that allow us to see the depth of Foucault’s readings in his seminars. We would like to insist that these readings were not suggested as final ones, but as “pistes de recherche” for those who were continuing their studies at the other academic institutions.

Guerry, A.-M, and S F. Lacroix. Essai sur la statistique morale de la France: précédé d’un rapport à l’académie des sciences. Paris: Crochard, 1833. There are many similar publications from the same period of time, including the cartography for such a statistics about crimes, like the one contained in Balbi and Gerry’s Statistique comparée de l’état de l’instruction et du nombre des crimes dans les divers Arrondissements des Académies et des Cours Royales de France. Gerry’s Statistique morale (which is an expression, or maybe a concept, that enjoyed some fortune in nineteenth century printed books), was translated and summarized in English in 1836.

As one of the main demographical sources, Foucault refers to Moheau, Jean Baptiste, and Montyon. Recherches et considérations sur la population de la France. Paris: Moutard, 1778.

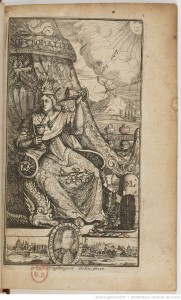

At the end of his first lesson, Foucault devotes some time to Alexandre de Maitre’s La Métropolitée, published in 1682.

It is well known that Foucault is extremely interested in the physiocrats and physiocracy. Foucault reads some of the early treatises, including Vincent de Gournay and his disciples, like Louis-Paul Abeille.

Among the less-known treatises on government techniques, Foucault reads not only canonical political treatises, but also others that are part of the popularization of political thought and political knowledge in the first years of the expansion of the printing press, including Guillaume de la Perrière, Tholosain. Le Miroir politique, contenant diverses manières de gouverner & policer les Républiques qui sont, & ont esté par cy devant. Œuvre non moins utile que necessaire à tous Monarches, Rois, Princes, Seigneurs, Magistrats & autres qui ont charge du gouvernement ou administration d’icelles. Paris: Robert le Mangnier, 1567. This book is also interesting because of the genealogy of the miroir genre he does at the beginning, addressing it to the garde des sceaux –with the excuse that they both were from Toulouse. Another important set of publications studied by Foucault is Nicolas de la Mare, Traité de la police, which was published several times, provoking lasting debates. Foucault interests cover the question of the ragion di Stato (see also here) with special interest in Giovanni Botero’s Della ragion di Stato dieci libri, published in Paris in 1599.

Foucault’s interest in the “pastoral” begins with his analysis of well-known Greek texts. Latin Christian texts, specially from Migne’s Patrologia Latina, constitute an important part of his research (as even the biblical texts insist on Abel as a “pastor”). One of the main centers of attention, besides Augustin’s De Civitate Dei, was Gregory’s Regula pastoralis.