By Bernard E. Harcourt

In the end, it is the third epigraph we discussed at our seminar that will serve as epilogue to the first set of Foucault’s lectures at the Collège de France, Lectures on the Will to Know (1970-1971):

“to sum up all of these steps, … we will have put the game of truth back in the network of constraints and dominations. Truth, I should say rather, the system of truth and falsity, will have revealed the face it turned away from us for so long and which is that of its violence.” (LWK, p. 4).

This passage underscores, so eloquently, the stakes of our enterprise: the violence of the system of truth and falsity. It is that violence that I would like to explore here again to close Foucault 1/13, drawing on the death penalty case I mentioned briefly and on the method of retrospective analysis that my colleague, Jesús R. Velasco, so brilliantly articulated yesterday.

A retrospective analysis, I take it, must begin at the end—for me, here, the present. A most immediate present. The last iteration in a decades-long struggle to the death.

This particular struggle plays out in the form of a judicial joust, but a joust that is neither equal from the start, nor intended to discover any truth. Just like the chariot race between Menelaus and Antilokus, this competition is not balanced. The parties are not of equal standing. Judges will declare a victor between the two, but the latter are unevenly matched. Everything will turn on a determination of fact, yet only one party will be given the scepter.

This joust, like the chariot race, is not a question of who will win. The social order is determined ahead of time. It is not about who is faster on their chariot, who is stronger, whose horses are better; it is not about who has the stronger evidence, or the better argument. Nor is it about who is right, which facts are true, what actually happened.

For in this struggle, a sovereign party—the state of Alabama, through its Attorney General—is gifted sovereign power, or more precisely the judicial quill. And so, on habeas corpus review in the state court of Alabama—where all the facts are found—the state of Alabama gets to write the judicial opinion.

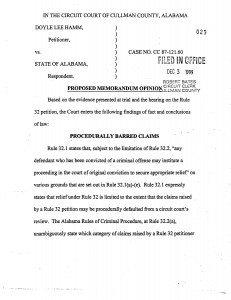

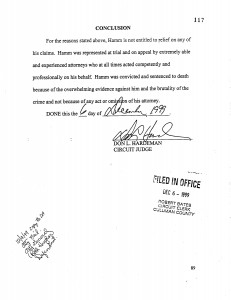

On Friday, December 3rd, 1999, the Alabama Attorney General submits his 89-page “proposed memorandum order” to the clerk of the court.

It is date stamped, and “filed in office” that afternoon.

The very next business day, Monday December 6, 1999, an Alabama judge signs the “proposed memorandum order,” making it his own, without even striking the word “proposed.”

It is “filed in office” December 6, 1999.

And no one blinks. The joust goes on for another round, and then another, and another, but no one seems to notice that three voices had become two, or one.

“In the system we know today,” Foucault wrote in his manuscript of February 3, 1971, “in the system already installed in the Greek classical epoch, the truthful utterance is above all that of testimony; it has the form of the factual observation; it rests on what has taken place and its function is to reveal it,” (LWK, p. 84-85).

“In the system we know today,” Foucault wrote in his manuscript of February 3, 1971, “in the system already installed in the Greek classical epoch, the truthful utterance is above all that of testimony; it has the form of the factual observation; it rests on what has taken place and its function is to reveal it,” (LWK, p. 84-85).

That, surely, is the discourse today. But it reflects only an imagination of “the system we know today.” An aspiration for some; a cover for most. Some call it an ideology. Others, an illusion.

It is seen by all, yet by none.

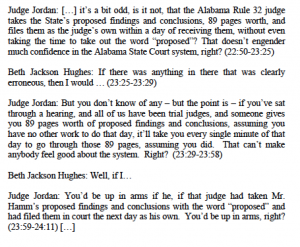

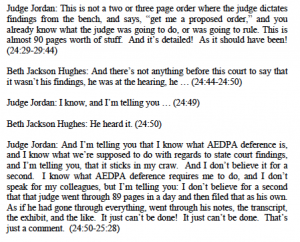

In Doyle Hamm’s case, not even the noblest, most august federal appellate judges blink. One federal appellate judge, at oral argument, acknowledges what everyone else sees: the state judge couldn’t possibly have read the state attorney’s proposed order.

“I don’t believe for a second that that judge went through 89 pages in a day and then filed that as his own,” Judge Adalberto Jordan of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit declares at oral argument. “As if he had gone through everything, went through his notes, the transcript, the exhibit, and the like. It just can’t be done! It just can’t be done.” (Oral argument at 24:50-25:28).

“I don’t believe for a second that that judge went through 89 pages in a day and then filed that as his own,” Judge Adalberto Jordan of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit declares at oral argument. “As if he had gone through everything, went through his notes, the transcript, the exhibit, and the like. It just can’t be done! It just can’t be done.” (Oral argument at 24:50-25:28).

The federal judge recognizes the audacity. But has little more to say. “That’s just a comment.”

And despite it all, the panel of three, august, federal appellate judges ends up seeing it as no more than a “procedural shortcut.”

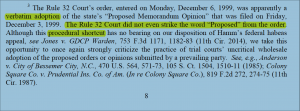

The federal judges do acknowledge, in an orphan footnote to their unpublished panel opinion (depriving Doyle Hamm of the precedential effect and import of the judgment, thus reducing his chances at the next round), that “The Rule 32 Court did not even strike the word ‘Proposed’ from the order.”

But that mere “procedural footnote” is of no real consequence. A slap on the wrist at most.

And so the joust continues, as it must, as it only can. It turns into a battle over time. A dual over the clock. Another hurdle, another petition, another appeal, another filing. Rehearing today, certiorari tomorrow.

In a debate a couple of months after his first lecture series, in a discussion with Benny Lévy and André Glucksmann in June 1971 titled “On Popular Justice,” Foucault strenuously resists the turn to the judicial model as a means of resistance. He emphasizes how, throughout the long history of judicial practices, the penal system has served as a device of repression. “The judicial system, as a state apparatus,” he underscored, “has historically been of absolutely fundamental importance” in fragmenting resistance, in turning some into dangerous individuals, in drawing the line between political and common law prisoners.

Resistance and disobedience, Foucault suggests, “can only take place via the radical elimination of the judicial apparatus.” Foucault is adamant:

“anything which could reintroduce the penal apparatus, anything which could reintroduce its ideology and enable this ideology to surreptitiously creep back into popular practices, must be banished. This is why the court, an exemplary form of this judicial system, seems to me to be a possible location for the reintroduction of the ideology of the penal system into popular practice. This is why I think that one should not make use of such a model.” (Dits & Écrits Quarto I, #108, p. 1220; Power/Knowledge p. 16)

Perhaps. And perhaps indeed the discursive methods of the G.I.P. were a far better mode, as Foucault suggested in March 1971, “to transform the individual experience into collective knowledge—that is to say, into political knowledge.”

But Doyle Hamm does not have that choice. The state of Alabama, with its bourreau impatiently waiting to strap Doyle Hamm onto the gurney, faces down one man in isolation, filing another petition, throwing another next legal hurdle, desperately trying to save his life.

And so the joust, over time, reveals its true face: a contest over whether a man shall die from a lethal injection intravenously administered, or whether he shall be allowed to die in the confines of his solitary cell, the cell in which he has been isolated since 1988—to die, that is, of the cancer that is eating away at his body.

This game of truth, it turns out, is stacked. It was determined from the outset by the order in which the contestants rose to do battle—as it was in the Homeric chariot race, the ritual to honor Patroclus’ funeral. The State of Alabama, first, versus Doyle Hamm. And when the state judge signed the Attorney General’s proposed order on December 6, 1999, he consecrated the social order.

“A thing there is, whose voice is one;

Whose arms are two, or rather one, then none.”