We know now that Donald Trump will take office as the United States’ 47th president this January, and that his stated desires for federal climate policy include withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, easing restrictions on oil drilling, and “rescind[ing] all unspent” Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funds. For climate-forward cities, the change in presidential administrations will usher in a fundamental shift – from an era in which cities had in the federal government a strong partner to one in which they will shoulder much more of the transition to a healthy, just, clean energy economy. In these early days, no expert can foresee the exact executive, regulatory, legislative and legal changes that will accompany this remaking of federal climate policy, but I can share what aspects of federal law and policy – from the IRA to the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Commitment to agency staffing – I’ll be monitoring to help cities continue to make progress on addressing the climate crisis. I do not claim to have all of the answers, but I hope that the following can serve as an early and shared research and tracking agenda for local climate policymakers and the community of practice that serves them.

We know now that Donald Trump will take office as the United States’ 47th president this January, and that his stated desires for federal climate policy include withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, easing restrictions on oil drilling, and “rescind[ing] all unspent” Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funds. For climate-forward cities, the change in presidential administrations will usher in a fundamental shift – from an era in which cities had in the federal government a strong partner to one in which they will shoulder much more of the transition to a healthy, just, clean energy economy. In these early days, no expert can foresee the exact executive, regulatory, legislative and legal changes that will accompany this remaking of federal climate policy, but I can share what aspects of federal law and policy – from the IRA to the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Commitment to agency staffing – I’ll be monitoring to help cities continue to make progress on addressing the climate crisis. I do not claim to have all of the answers, but I hope that the following can serve as an early and shared research and tracking agenda for local climate policymakers and the community of practice that serves them.

Before diving into the research agenda, I want to reassure local government officials and staffers that a lot of people will be monitoring the items I list below and advising cities on how to proceed (the Sabin Center’s IRA Tracker already aggregates agency publications on IRA programs). Sustainability staffers need not manage these risks alone. More to the point, nothing here should be taken to suggest that cities slow their efforts to mitigate and respond to climate change. Federal programs like the grants, tax credits, and Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund programs are available now, and if they are undone by the Trump administration or by Congress it will take time. Local governments and sustainability offices should plow forward as they are able, and trust that city networks, advocates and experts will keep them apprised of relevant developments.

Inflation Reduction Act

The IRA, enacted in 2022, thoroughly refashioned cities’ approach to climate action and to collaborating with the federal government to pursue shared environmental goals. Hundreds of billions of dollars in grants and tax credits were made available to local governments to pay for their clean energy, electric vehicle, and green building projects, with much more money flowing to community groups, businesses, and residents to advance their own climate work. Trump has indicated that he would like to repeal parts of the IRA but, as my colleagues found in their September 2024 paper, much of the grant money has already been obligated. Red and purple districts have received most of the funding and, as a result, some Republican members of Congress have expressed opposition to repealing the law. Still, more surgical strikes on targeted IRA provisions and on the implementation of IRA programs that are not repealed are very much on the table.

Tax credits & elective pay: Much of the IRA’s projected spend comes in the form of tax credits for clean energy and clean transportation. As previously discussed in depth on this blog, the IRA also makes certain tax credits usable directly by local governments and other nontaxable entities through elective pay. These tax credits are enshrined in statute, as is the right to claim them by elective pay. In other words, the Trump administration cannot repeal them through executive action alone. Options remain to weaken or eliminate these tax benefits, however, and two in particular stand out. First, Congress could repeal or change the terms of tax provisions through reconciliation legislation, a special procedure by which Congress can enact budgetary measures without a filibuster-proof 61 votes in the Senate. Many tax provisions are enacted and modified through reconciliation legislation, including the IRA itself. Republicans have already been talking about extending Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, and they might enact legislation that changes or eliminates the IRA’s tax credits alongside other changes to the tax code.

Second, the administration could use executive actions to preclude the efficient implementation of the tax credits and the elective pay program. The Treasury Department has issued thousands of pages of rulemakings and guidance that set out practically how the tax credits work and can be claimed. Many of these rules have gone through the rulemaking process, including a notice and comment period, meaning that they cannot be changed until the new administration amends them through the same formal process. Still, under the Trump administration, Treasury may start those rulemaking processes relatively quickly and get at least a few rules amended by sometime in 2026. (Certain electric vehicle and prevailing wage and apprenticeship rules, which were finalized in May and June, respectively, may be more vulnerable to rollback by the Congressional Review Act in January 2025, depending on the composition of the new House of Representatives and the date on which Congress ends its 2024 session.) New rules could make it more difficult or less clear as to how to claim tax credits through elective pay, even if a local government is statutorily entitled to them. More tangibly, the IRS is responsible for managing key parts of the elective pay filing process, including the preregistration portal and periodic office hours to answer filer questions, and the Trump administration may reduce staff or eliminate key offices within the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), including in the tax-exempt and government entities division.

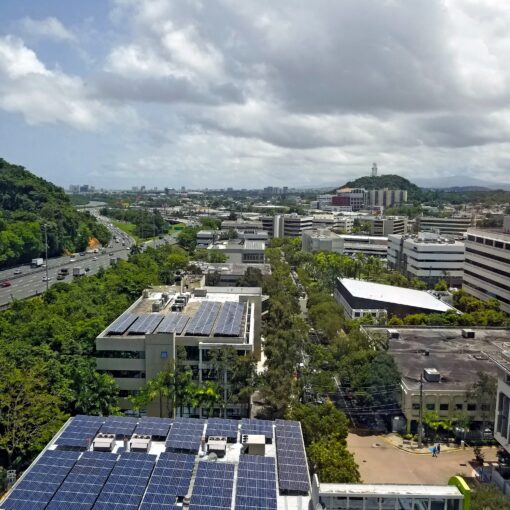

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF): The GGRF is a three-pronged IRA program that seeds a nationwide green finance network. The $27 billion appropriated for GGRF have been committed in contract – an important legal milestone – but the grantees’ programs and financial product offerings are in the very early stages of implementation. It is important to note here the basic structure of GGRF, in which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) makes grant awards to three National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF) grantees, five Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA) and 60 Solar for All grantees, each of whom then make further loans or grants to others. Thus, while the EPA has duly obligated GGRF funds to its immediate grantees, implementation by those grantees is a separate process that has only just begun.

Moreover, GGRF money gets drawn down by grantees over time; it is generally understood that GGRF funds are held in accounts outside of the federal government for transfer to grantees’ ledgers only when needed. However, grant contracts are confidential and, for the most part, cities are not direct grantees, so there is little public visibility into implementation mechanics. It is possible that Trump will seek to dismantle GGRF programs. Given the opacity of the GGRF contracts, it’s hard to say exactly what actions the Trump administration might take. Over the coming months, I will be watching for protections from the Biden administration and elsewhere to ensure the continued availability of grantee funds, as well as any Trump administration efforts to limit access to committed grant amounts.

Navigating through GGRF was going to be complicated regardless of administration. The federal grantees, which are private entities, will have their own programs and priorities, many of which will be imperfect fits for local government needs. The funds, however, will flow into community projects and in some instances to local governments directly, making these programs important ones to monitor. Therefore, in addition to the grant awards from the EPA to the grantees, there will be a need to watch for changes or challenges in how the grantees themselves implement their awards. For example, GGRF grantees have obligations to direct a portion of their capital into disadvantaged communities. The IRA provisions establishing the GGRF made this difficult enough, providing comparatively few resources to staff an oversight office. Under Trump, the EPA will have little interest in delivering environmental and equity benefits to disadvantaged communities, and it will be incumbent upon advocates and experts to track the GGRF grantees’ follow-through on their commitments.

Finalizing grant contracts, and grant programs that remain open: There are at least tens of millions of dollars of announced grant awards for which formal contracts between the grantee and the relevant federal agency have not been finalized. This is a critical gap – from a legal perspective, a signed contract is significantly more durable than the announcement of a grant award (though failing to move forward with an announced award may have political consequences). While there are no guarantees, agencies will have a much harder time getting out of commitments they made in contract. The Biden administration has indicated that it plans to get many of these contracts signed by the time Trump takes office. This will be a significant undertaking. Local governments with grant agreements still under negotiation should aim to formalize those agreements as expeditiously as possible, including moving them through any internal reviews or processes that might hold them up at the eleventh hour. Cities should pay close attention to terms that it could have trouble complying with, if the relevant agency is open to negotiating them in the time that remains. A more actionable suggestion may be that local governments should ensure that internal controls are in place to comply with the terms of any grant agreement, to avoid giving a Trump-controlled agency a hook on which to claim the contract has been breached.

Less clear is how open grant programs for which awardees have not been named will proceed. The Community Change Grants program, for example, remains open to applications on a rolling basis until November 21, 2024. Local governments and others interested in pursuing these grant programs should reach out to their agency contacts to gauge the likelihood of any grant applications reaching the signed agreement stage by January 20, 2025.

In the coming months, I would expect technical assistance services to emerge to help local governments finalize their open grant agreements. In 2025 and beyond, a community of practice will need to develop to help cities and other IRA grantees ensure continued compliance with their grant agreements, especially if those agreements involve payment of grant amounts in tranches. It will also be critical for grantees to carefully document how grant funds are being spent, work that’s been performed in furtherance of the grant agreement, and other reporting requirements laid out in contract in the event of a review by the Trump administration in connection with disbursing future funding tranches.

Home energy efficiency and electrification rebates: The IRA included nearly $10 billion in rebates for residential energy efficiency and electrification projects, largely though not exclusively for low-and middle-income households. These rebate programs were designed to be run through each state’s energy office: the state energy office would develop its rebate program (consistent with federal parameters), apply for the funds allotted to it on a formula basis, and launch and administer the program for its residents. Currently, nine states plus Washington, DC are offering rebates, another ten have had their program applications approved by the Department of Energy (DOE), and more than twenty have yet to submit program applications at all. As my colleagues’ research suggests, it would be difficult for the executive branch alone to reallocate more than ten percent of the funds allocated to any program under the IRA. However, Congress could do so, including in its potential reauthorization of the 2017 Trump tax cuts.

Without the contracts between states and the DOE, the vulnerability of the rebate programs is difficult to assess, but a signed grant agreement is a critical milestone. Where rebate programs are already operational, states will be able to rely on the legal enforceability of their agreements, though Trump DOE’s may take steps to make the programs more difficult to carry out (e.g., by understaffing the relevant DOE offices or holding up review of applications) For states without rebate programs in place yet, it is not too late. The rebates are codified in law, and they remain there unless and until Congress changes the law. States should work swiftly to move their program development, application, or grant agreement negotiations along. (Though the rebate programs are grants to states, I include them in my analysis here because cities will rely on their states to provide rebates to local households, and because in some places cities may play a role in pushing their states to advance their rebate programs.)

Beyond the IRA

Justice40 and Disadvantaged Communities: It is almost a certainty that President-elect Trump will rescind Biden’s Executive Order 14008 of 2021, which declared “environmental and economic justice [as] key considerations in how we govern.” It is not uncommon for a new president to formally or informally revoke a previous administration’s policies, and there likely will be many ways in which the turn away from environmental justice as an animating principle bears out. With respect to cities, there are two significant implications I’ll be watching: the Justice40 commitment and the Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CJEST). The Justice40 commitment pledged that forty percent of the benefits of certain federal climate and clean energy spending would go to “disadvantaged communities.” Executive Order 14008 did not directly define “disadvantaged communities” (other than referring to them as “historically marginalized and overburdened”), but rather directed CEQ to develop a geospatial tool – CJEST – that would show where in the country disadvantaged communities are located based on criteria developed by CEQ and a White House Environmental Justice Advisory Board.

The term “disadvantaged community” flows through the IRA, including in provisions establishing the GGRF, Environmental and Climate Justice Block Grants, the residential energy efficiency and electrification rebate programs, grant programs for port decarbonization, and funding to reduce air pollution at schools and elsewhere in low-income communities, among other programs. Agency guidance and decision-making for programs like GGRF depend heavily on CEQ’s definition of “disadvantaged communities” in directing funding and in making foundational decisions about the program’s direction. While it is safe to assume that the Trump administration will direct less federal climate and clean energy spending to disadvantaged communities, it is not yet clear how else the lack of a common definition for, or a changed definition of, “disadvantaged communities” will ripple into other areas at the intersection of federal and local climate action.

Staffing in federal agencies: Project 2025, widely viewed as a blueprint for the Trump administration, has a significant focus on winnowing down federal agencies. That has widespread implications for environmental and energy programs, of course, but I’ll be watching specifically for changes to the offices that serve local governments and their allies. These include the Tax-Exempt & Government Entities Division at the Internal Revenue Service, DOE’s Office of State and Community Energy Programs, EPA’s Local Climate and Energy Program, and staffing for IRA programs like GGRF, the Climate Pollution Reduction Grants (CPRG) and support for developing community benefits agreements. Project 2025 also proposes eliminating the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which hosts the National Hurricane Center, among other offices. Depending on key staffing decisions, programs that local governments rely on for support could become less accessible or be eliminated entirely.

Rollback of environmental rules: During the first Trump term, federal agencies took more than 150 actions to roll back environmental protections, and it stands to reason that the deregulatory agenda will continue apace. On Monday, Trump wrote of his likely nominee to head the EPA, Lee Zeldin: “He will ensure fair and swift deregulatory decisions.” Environmental deregulation will have implications across the country and the economy, though local governments are uniquely positioned in that they rely on the federal government to regulate in sectors where they cannot. Academics (including the Sabin Center) and journalists closely tracked environmental deregulation during the first Trump administration, and I expect that activity will resume. As for environmental rules especially relevant to cities, I will be tracking the Biden administration’s 2024 powerplant rules, IRS rulemakings with respect to tax credits and elective pay, and the several regulations limiting emissions from light and heavy duty vehicles (including developments with respect to the so-called “California waiver,” which allows the state of California to set its own vehicle emission standards that other states may also adopt). I’ll also be watching for changes in the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s and other agencies’ environmental review processes for the siting of fossil fuel infrastructure, as contemplated by Project 2025. In addition to executive branch actions, litigation surrounding these various rules – and in particular the Department of Justice’s willingness or not to defend them – is an important part of the overall picture. We at the Sabin Center have submitted several amicus briefs on behalf of the National League of Cities and the US Conference of Mayors advocating for robust federal environmental protections to bolster local governments’ climate efforts, and these opportunities for local advocacy are sure to remain critical.

* * *

The federal-local relationship will have a different tenor in 2025 than it has for the past four years, but the near- and medium-term actions cities might take to mitigate and respond to climate change need not change abruptly. Tax credits, elective pay and the GGRF are all operational now, and signed grant agreements will remain legally binding after President-elect Trump is inaugurated.

Moreover, many of the actions local governments take to address climate change – updating building codes and standards, changing zoning codes to facilitate more environmentally-friendly development patterns, implementing composting programs, and the like – are wholly separate from the federal government. Where federal actions put local climate policy at risk, local governments will need to protect their progress and continue taking advantage of federal programs where they exist. In those efforts, a careful eye from advocates and experts on changes at the federal level will be key to helping mitigate potential damage.

Amy Turner is the Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.