This blog post was authored by 2024 Sabin Center Summer Intern, Arpana Giritharan, with input and supervision from Johanna Lovecchio, Director of Program Design for Climate Action and Adjunct Professor at Columbia Climate School, and Romany Webb, Deputy Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

‘Coastal blue carbon’ refers to the carbon captured by living coastal and marine organisms and stored in coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves, seagrasses, and tidal or saltwater marshes. Scientific research indicates that blue carbon ecosystems (BCEs) can sequester up to four times more carbon per hectare and store it 30 to 50 times faster than terrestrial forests. They also provide crucial co-benefits, including enhanced coastal resilience and improved livelihoods, making them important for both climate change mitigation and adaptation.

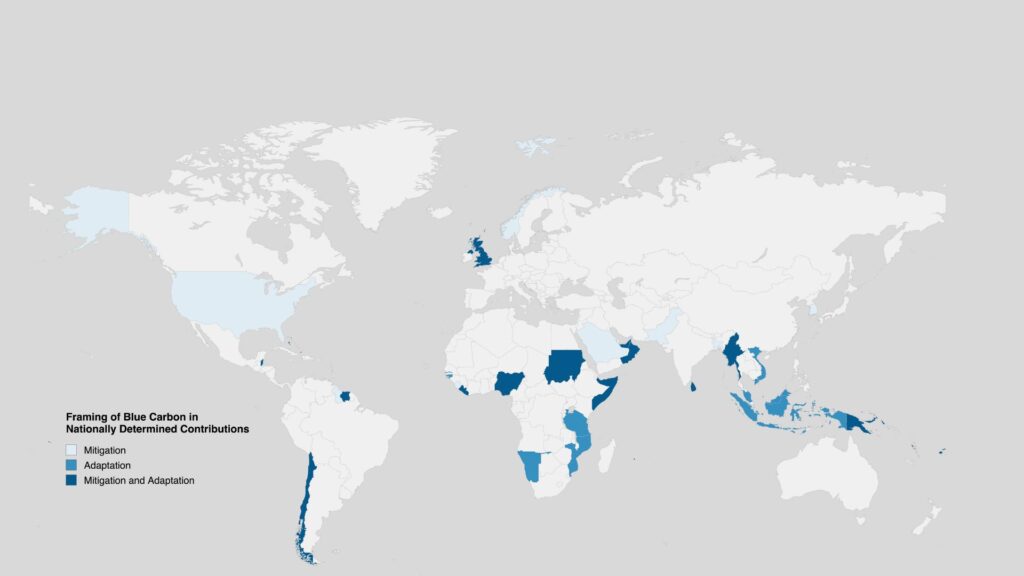

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that around 151 countries have at least one blue carbon ecosystem (BCE), with 71 countries possessing all three types. However, only 42 jurisdictions have acknowledged the importance of blue carbon as a climate mitigation and adaptation strategy in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted under the Paris Agreement. Countries are expected to unveil updates to their NDCs by early 2025 and are urged to recognize the significance of BCEs in these updates.

Although in its early stages, carbon dioxide removal (CDR) techniques – i.e., techniques that remove and store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere – have gained traction in recent years as a climate change mitigation strategy. The IPCC has emphasized that although CDR cannot replace substantial emissions reductions, its deployment is “unavoidable” to avert the most severe consequences of climate change.

We analyzed 141 parties’ NDCs to identify whether blue carbon is framed as a mitigation or adaptation strategy, if they discussed blue carbon at all. We were unable to review the NDCs submitted by 53 parties as they were not published in English. For each NDC we reviewed, we searched for the keywords “blue carbon,” “carbon sink,” “wetland,” “mangrove,” “saltmarsh,” “seagrass”, as well as broader terms such as “blue economy” and “ocean”. Relevant phrases from NDCs, including these terms, were extracted and analyzed. Based on the analysis, the NDCs discussing blue carbon were grouped into three categories: (1) those that presented blue carbon as a mitigation strategy, (2) those that presented blue carbon as an adaptation strategy, and (3) those that discussed blue carbon in the context of both mitigation and adaptation. The map below shows the results.

Of the NDCs reviewed, forty discussed blue carbon, with varying degrees of emphasis. Of those, 12 identified these ecosystems as solely a mitigation strategy, 8 identified them under adaptation strategies, and 22 identified them as both mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The level of detail and ambition regarding blue carbon varies across NDCs. Of the NDCs that discuss blue carbon, the majority acknowledge the potential of blue carbon for adaptation and mitigation. Some, such as the Seychelles’ NDC, include more specific targets such as to “protect at least 50% of its seagrass and mangrove ecosystems by 2025 and 100% by 2030, with external support,” and to “include the greenhouse gas (GHG) sink of Seychelles’ blue carbon ecosystems in the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory by 2025.”

NDCs do not fully outline how BCEs will be scaled up through funding. Several countries mention the prospect of investing in coastal resilience, but do not go beyond this. Seychelles, is an exemplary case, as it specifies the use of innovative financing mechanisms such as blue carbon credits and bonds, and debt-for-nature swaps (p.20) in financing BCEs, and the blue economy more generally. Some NDCs discuss broader funding programs, such as Somalia’s target of $3 billion for ‘coastal, marine environment and fisheries’ which include BCEs.

While acknowledging blue carbon in NDCs is a step in the right direction, there are still certain limitations related to including them in NDCs. Although the Paris Agreement (Article 4, Paragraph 2) legally requires parties to submit NDCs and “pursue domestic mitigation measures with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions”, the actual fulfillment of the NDC is not legally binding or enforceable. Further, mentions of voluntary carbon markets which could be a forthcoming driver of BCEs were beyond the scope of our search. There are several challenges with this due to the credibility of carbon credits, issues with additionality, and regulatory uncertainty.

Additionally, some countries’ may have mentioned blue carbon in other climate policy documents such as National Adaptation Plans, or various ocean strategies, without mentioning them in NDCs. An example of this is the Biden-Harris Administration’s 2023 Ocean Climate Action Plan (OCAP) which identifies conservation and restoration of BCEs as a tool for addressing the climate crisis. Australia is another example. While Australia’s NDC does not mention BCEs, they have adopted comprehensive regional blue carbon strategies (e.g. NSW Blue Carbon Strategy 2022–2027 and Blue Carbon Strategy for South Australia) and provided funding for blue carbon restoration and conservation projects overseas through the Blue Carbon Accelerator Fund.

Regulations, and enforcement by organizations, have played a crucial role as a policy lever to protect BCEs from various threats such as aquaculture. For example, Sri Lanka was the first country in the world to legally protect its remaining mangrove forests in 2015. Environmental Foundation Lanka (EFL) – a public interest law group – filed a Fundamental Rights Petition (SCFR 150/2024) in the Sri Lankan Supreme Court in June 2024 seeking due protection for the Vidattaltivu Nature Reserve, the country’s largest marine protected area, which comprises all three BCEs. The Supreme Court granted the petition and ordered the then-Minister of Wildlife and Forest Conservation to reinstate protections for the area that had previously been removed. This success is one of many which highlights the importance of leveraging legal and policy tools to protect existing BCEs.

Countries which classified blue carbon as a mitigation measure in NDCs: Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Guyana, Norway, Pakistan, Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and the United States of America.

Countries which classified blue carbon as an adaptation measure in NDCs: Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mozambique, Namibia, United Republic of Tanzania and Viet Nam.

Countries which classified blue carbon as both mitigation and adaptation measures in NDCs: Bahamas, Belize, Chile, Fiji, Liberia, Maldives, Mauritius, Micronesia (Federated States of), Myanmar, Nigeria, Oman, Papua New Guinea, Saint Lucia, Samoa, Seychelles, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Vanuatu.

For a detailed analysis of the 141 NDCs we reviewed, see this spreadsheet.

Arpana Giritharan

Arpana Giritharan is a legal intern at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and a master's student at Columbia Climate School. This blog discusses the work she conducted as a departmental research assistant at the Climate School.