In April 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced funding recipients for its National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF) and Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA), two programs established by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The NCIF and CCIA awards are a step towards implementing the “third leg of the stool” with respect to the IRA’s funding and financing offerings to municipal governments and community benefit organizations (CBOs): (1) direct grants to local governments and their partners; (2) tax credits for which an elective or “direct” payment option is available; and (3) low cost loans from green banks and other sources of private capital catalyzed by green bank investments. As with many other aspects of the IRA, local governments will need to play an active role in ensuring that NCIF and CCIA funds are used to advance both their own climate goals and those of their residents and local community groups, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

In April 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced funding recipients for its National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF) and Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA), two programs established by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The NCIF and CCIA awards are a step towards implementing the “third leg of the stool” with respect to the IRA’s funding and financing offerings to municipal governments and community benefit organizations (CBOs): (1) direct grants to local governments and their partners; (2) tax credits for which an elective or “direct” payment option is available; and (3) low cost loans from green banks and other sources of private capital catalyzed by green bank investments. As with many other aspects of the IRA, local governments will need to play an active role in ensuring that NCIF and CCIA funds are used to advance both their own climate goals and those of their residents and local community groups, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

Both the NCIF and CCIA were established by the IRA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), and are referred to as “green bank” programs, meaning that the entities they fund are expected to “provid[e] an immediate pathway to deploy projects” and “mobilize private capital at scale.” (A third element of the GGRF is the Solar for All program, which is not a green banking program; local governments will mostly access Solar for All program funds via partnerships with state and nonprofit grantees.) Green banks predate the IRA, but their geographic and financial reach has been limited. The GGRF seeks to supercharge green banking with a $20 billion infusion to the winning NCIF and CCIA applicants, with some of those funds to be loaned out by the grantees themselves and others routed through community partners such as community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and credit unions (together, “community lending partners”).

To date, guidance and advocacy with respect to the green banking elements of the GGRF have largely focused on helping EPA shape the programs and would-be green banks prepare their funding applications. While cities were not eligible to apply for NCIF and CCIA funds during the 2023 grant application periods, they are now set to become key players in the green banking ecosystem. Cities and other local governments will serve as customers for financial products and services offered by the NCIF and CCIA winners and as connectors between these banks, community lending partners, and the broader community.

GGRF Grantees and Their Likely Market Roles

The NCIF is granting its $14 billion to three national nonprofit lending institutions: (1) the Climate United Fund, (2) the Coalition for Green Capital, and (3) Power Forward Communities. According to the NCIF’s Notice of Funding Opportunity, grantees are “to create national clean financing institutions capable of partnering with the private sector to provide accessible, affordable financing for tens of thousands of clean technology projects nationwide.” Per EPA’s grant announcements, Climate United Fund “will focus on investing in harder-to-reach market segments like consumers, small businesses, small farms, community facilities, and school;” Coalition for Green Capital “will have particular emphasis on public-private investing and will leverage the existing and growing national network of green banks as a key distribution channel for investment;” and Power Forward Communities will focus on housing, “providing customized and affordable solutions for single-family and multi-family housing owners and developers.” These groups will each offer financial products and services directly rather than through community lending partners.

The CCIA, with its $6 billion in funding, makes grants to hub nonprofits that will provide funding and technical assistance to community lenders around the country to help those entities offer green banking products and services in low-income and disadvantaged communities. Each grantee works with a different group of community lenders, and it will take some time for money to flow from the grantee hub to the lenders it serves. The five grantees are: (1) Opportunity Finance Network (works with Treasury-certified CDFIs); (2) Inclusiv (CDFIs and financial cooperativas in Puerto Rico); (3) Justice Climate Fund (range of community lenders); (4) Appalachian Community Capital (community lenders in coal, energy underserved rural, and Tribal communities); and (5) Native CDFI Network (Native CDFIs). For the most part, CCIA funds will not flow directly to borrowers but rather to each of their respective local lending partners, which will then offer financing products to consumers including local governments, CBOs, businesses, and households and residents. For both programs, but for the CCIA in particular, it will take some months for the GGRF dollars to flow due to the administrative burden of standing up these new entities and getting grant agreements signed.

Filling Financing Gaps (Including Those Left by other IRA Programs)

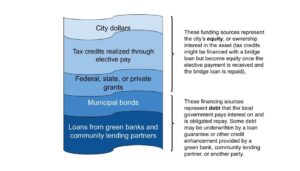

The main direct way that green banks stand to benefit cities is through low-cost financing products that can fill the gaps in funding that are left when tax credits, grants, bond proceeds, and other sources of capital are exhausted. In the renewable energy development space, project developers generally finance a project according to a “capital stack,” that is, a combination of funding and financing sources that together pay for a project’s development (and, in more complex stacks, prioritize which lenders and investors are paid first with project proceeds). A simple capital stack, and one that could be used to fund a local government renewable energy project, could include funding from the city, elective payment of a tax credit, a federal, state, or nonprofit grant, and one or more sources of debt. The capital stack would look like this:

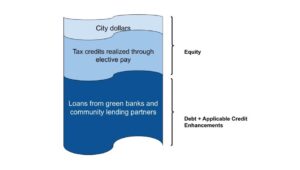

A local government could have fewer sources of capital for a project, with no grants and limited funds from the city itself. In such a case, the debt portion of the capital stack would be larger:

A green bank could provide the debt financing portion of the capital stack, ideally at a lower interest rate than otherwise available commercially. While more complex projects will require individualized guidance on the appropriate capital stack, among other aspects of project structuring, it would be possible for national or regional technical experts, or for the green banks and community lending partners themselves, to develop model capital stacks that local governments can plug their smaller, less complex projects into. For example, a green bank could offer a streamlined product that combines elective payment of the clean energy Investment Tax Credit (ITC), a small amount of city-provided cash, and low-interest debt for the balance of a renewable energy project below a specified size. Or a loan with payback terms for an electric vehicle purchase that is comparable to or better than lease terms. Or other products developed with input from local government groups that respond to cities’ needs.

Green banks can also offer “credit enhancements” such as loan guarantees (a promise to repay a defaulted loan), loan loss reserves (partial coverage of private lenders’ losses), and subordinated debt (loans that are repaid last, after all other lenders have been made whole) to make traditional lenders more comfortable extending credit for clean energy projects. Some green banks use a tool called securitization, in which they package loans together to mitigate risk. A local government – or perhaps an instrumentality such as a municipal utility – might include such a credit enhancement in its capital stack alongside more traditional loans.

At this time, it is not clear what financial products green banks will offer. As noted above, the five grantees will need to get their operations up and running before they make their first loans. Given the time it takes to finalize the grant agreements between USEPA and each grantee, the agency anticipates issuing funds to NCIF and CCIA grantees beginning in July 2024, with all funds out the door by the September 30, 2024 deadline set in the IRA.

Addressing Timing Issues with Elective Pay

Elective pay (or “direct pay”) is a new feature of the tax code enabled by the IRA that allows nontaxable entities, including local governments and many CBOs, to collect as a cash payment the value of twelve climate and clean energy tax credits. As has been discussed previously on this blog, elective pay stands to significantly increase uptake of these tax credits and to transform the financing market for local clean energy and clean vehicle investment.

Elective pay has one significant drawback: timing. An elective pay claimant must purchase or put in service the asset for which it is claiming the tax credit well before it receives payment from the IRS, meaning that it needs to expend funds or otherwise arrange financing for the interim period. This financing gap could extend to well over a year based on the timing of tax filings, and to longer than that for complex, longer-to-build renewable energy projects.

Green banks could fill this gap by offering low- or no-cost bridge loans to cover project costs before the elective payment is made. A city or other elective pay claimant would then repay the green bank with the proceeds of the tax credit. While we do not yet know for sure what financing products green banks and their community lending partners will make available, bridge loans to cover this gap financing period would be an extremely simple, cost-effective, and impactful way for green banks and their partners to advance GGRF goals.

Outreach to Residents, CBOs, and the Private Sector and Back to Green Banks and Community Lending Partners

Many of the services green banks can provide to cities may also be extended to businesses, nonprofits, and households. For example, a loan loss reserve established by Michigan’s green bank allows residents to access credit for solar panel installations at lower interest rates, with no collateral, and with a lower credit score than more traditional loans. Loan guarantees are relatively common tools in private sector renewable energy development, and could play a role in nonprofit or smaller-scale private sector projects going forward, if green banks are willing to offer such a service. Green banks can also securitize portfolios of loans for all kinds of borrowers, allowing them to extend credit further afield than might a traditional lender. A green bank could offer pre-packaged financial products that meet the needs of a borrower completing a simple home upgrade project, for example. And a green bank or community lending partner may also be able to offer repayment schedules that better match the payback period on a building improvement project.

For nonprofits, smaller businesses, and residents, green bank offerings will be new, and we don’t yet know how broadly or well grantees or their local partners will advertise their services. Nonprofit CBOs and residents may benefit from knowledge resources developed by or with local governments, and from technical assistance in navigating green banks and community lending partners or in developing a project or its capital stack. Moreover, outreach runs in two directions – out to community stakeholders but also back to national, regional, and local green banks and green bank partners. Local governments can help shape their local lenders’ offerings – if the products and services offered by a local green bank are insufficient or misaligned to local needs, it may fall on local governments to bridge this divide.

Holding Green Banks Accountable

In shaping the green banking programs, EPA paid significant attention to two overarching concerns: (1) offering technical and financial assistance to low-income and disadvantaged communities, and (2) oversight, accountability, and effectiveness of green banking dollars. EPA will surely track its chosen accountability metrics through reporting requirements and other means, but local governments could also help. Along with community stakeholders, local governments have a front-row seat in assessing whether green banking dollars are used effectively and in the communities most in need of their services.

Each GGRF grantee has pledged 50 percent or more of its funds to disadvantaged communities, but how will they ensure that green bank funds actually reach or are accessible to members of such disadvantaged communities? Green banks and community lending partners will need to conduct their own outreach to understand community needs and educate residents and CBOs about available financing products and resources. Loan products will need to be tailored to communities – responsive to real needs, affordable and accessible to residents and CBOs, and without predatory terms or unintended consequences. Cities are well-positioned to see and report, in broad strokes, where green banking products are being used, what results they are driving, and what gaps in implementation remain.

Partnering with States, Technical Assistance Providers, and the Private Sector

The GGRF is the “largest non-tax investment” in the whole of the IRA; while local governments are key implementing partners in GGRF they should not have to go it alone. It is my hope that significant help and technical assistance from states, nonprofits, and the private sector emerge to help local governments and CBOs navigate new financial offerings, get needed investment dollars, and think broadly about developing projects and their capital stacks. Some states have their own green banks, or will be in a position to work closely with the NCIF and CCIA grantees and community lending partners to ensure GGRF dollars flow to the cities, CBOs, and residents that most need them. Some states might also consider setting up revolving loan funds or offering loan guarantees to supplement green bank offerings. As with other aspects of the IRA, a handful of states may show themselves to be unwilling partners in GGRF implementation. The good news in those instances is that NCIF and CCIA financing products can be accessed without state support, though state actions could make the underlying projects financed with these funds more difficult to undertake.

—————

The GGRF has the potential to change the game for renewable energy, building retrofit, and clean transportation financing in cities across the country. As with other marquee programs in the IRA – elective pay, Climate Pollution Reduction Grants, and more – local governments play a critical role in implementation. Municipalities will need to figure out how to finance their own projects with the use of green bank offerings, and their experiences can inform other local clean energy investment and offer learnings for stakeholders. Local governments that develop relationships with local community lending partners will be better positioned to empower their residents and CBOs to take advantage of these lenders’ offerings, and to communicate financing, technical assistance, and communication gaps. And local governments will provide important feedback to hold the green banks and community lending partners accountable. While there is still much to learn about the green banking ecosystem established by the IRA, local governments would be well-served to begin navigating this new space now.

Amy Turner is the Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.