by Michael Choi, Summer Intern

Last month, the United States delegation led international efforts to initiate a Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) amendment to the Montreal Protocol at meetings which took place from July 15th-23rd. The Montreal Protocol, which was adopted on September 16, 1987, is an international agreement to phase out the production and consumption of ozone depleting substances in order to reduce their abundance in the atmosphere and protect the stratospheric ozone. As noted by U.S EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy, the Montreal Protocol is regarded “as the most successful environmental treaty” since it has led to the 97% reduction in the production and import of ozone depleting substances throughout the world.

HFCs are fluorinated greenhouse gases that are used commonly in refrigeration, air conditioning, aerosols, fire protection systems and solvents. They have become increasingly prevalent because they serve as a substitute for the ozone-depleting substances that are being phased out under the Montreal Protocol, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). Although HFCs have not been proven to directly harm the ozone layer, they are extremely potent greenhouse gases.

The Montreal Protocol can be amended to ban substitutes for ozone depleting substances that harm the environment, even if the substances may not negatively impact the ozone layer. On November 6, 2015, the 197 parties that signed the Montreal Protocol pledged to monitor and limit the usage of HFCs and to pass an amendment by the end of 2016 regarding the phase out of HFCs. The parties did not reach a final agreement on the text of the amendment at last month’s meetings, but they hope to do so by October. According to EIA international, over 100 parties, including the US and EU, have now expressed support for an ambitious agreement with a HFC consumption freeze beginning in 2021.

Throughout the global conversations surrounding HFCs, the US State Department has stressed that the achievement of an HFC amendment to the Montreal Protocol would be “one of the most consequential and cost-effective actions that global community can take this year to combat climate change”. This is because HFCs can be thousands of times as climate-forcing per ton as C02 in the short-term. For example, the most prevalently used HFC, HFC-134a, which is commonly used in refrigeration and air conditioning systems, is 1,430 times more damaging to the climate system than CO2. Moreover, in the absence of regulation, experts predict a nearly twenty fold increase in HFC emissions in the coming decades, largely due to rising international demand for refrigeration and air conditioning services.

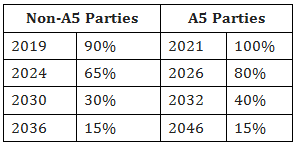

In 2015, the United States, Canada and Mexico submitted a joint North American proposal for the HFC amendment. The proposal would entail a gradual phasedown of HFC production and consumption, with differing obligations for developed countries (Non-A5 Parties) and developing countries (A5 Parties), as follows:

The US has estimated that this proposal would reduce 90 gigatons of C02e by 2050 and half a degree Celsius of warming by the end of the century.

The European Union (EU), India, and Island States also submitted their own proposals for the HFC phase out in advance of the meetings (a summary of all the proposals is available here). The EU and Island States proposals were both slightly more ambitious than the North American proposal, whereas the Indian proposal would grant significantly more leeway to developing countries to continue using HFCs over the next two decades.

India has argued that the cost of replacing HFCs with alternate coolants will negatively affect the residents of developing nations with warm weather, where the use of air conditioning is expected to soar in coming decades, because alternate coolants can cost up to ten times more than HFCs. Thus, India is advocating for a timeline for developing countries that phases out HFCs beginning in 2031, in order to ease the financial difficulties of switching to alternate coolants. In contrast, North America, Europe, and the Island States are in favor of an agreement which would require developing countries to begin phasing out HFC production and consumption starting in 2021. Responding to the concerns of India and other developing countries, Secretary of State John pledged on July 22 that the amendment would include financial “assistance from rich countries to help poorer ones deal with the cost of transitioning to the new chemicals”.

By the end of the Vienna meetings, the parties had tabled a range of ideas related to the baselines and appropriate timeframe for the phase-out of HFC production and consumption. As noted above, over 100 parties have reportedly expressed support for an HFC consumption freeze in 2021 (meaning that consumption could not increase after that year). This would be followed by a phase out or phase down of HFC production and consumption with different timelines for developed and developing countries. The parties hope to reach a final agreement by October of this year.