By Danielle Sugarman

Fellow

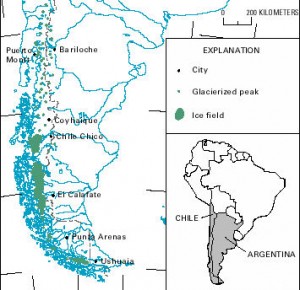

The glaciers in Patagonia provide Argentina with 70% of its safe drinking water. Yet, alarmingly, this vital resource is facing dual man-made threats; one from the persistent effects of climate change and another, less well known, from the foreign companies who mine for gold under the vast blocks of glacial ice. Argentina possesses a vast repository of mineral wealth. Under Argentina’s Mining Investment Law, mining ventures have been given a generous platform for the exploitation of these resources, and as a result, mining is a booming industry. But, as is often the case, short term profit has come at a cost to long term environmental considerations in the region.

Argentina’s mining operations require immense amounts of water and the mechanical equipment needed to extract gold and other minerals cause damage to the glaciers and permafrost (also known as periglacial areas which also serve as important sources of fresh water). Furthermore, the equipment and chemicals used in processing the extracted minerals contaminate the water that the glaciers contain. In open-pit mining, the most controversial mining technique, crushed ore is removed, soaked in chemicals such as cyanide and mercury, and after the “slurry” is removed, the contaminated water is often returned to the water table from which it came. Not only does the extraction directly pollute once pristine sources of water, but the extraction itself requires between 60 and 100 million liters of water per day.

Understanding the importance of glaciers not only for their vital reserves of water, but for the hundreds of thousands of tourists they attract to Argentina each year, politicians and environmentalists embarked on an effort to safeguard the glaciers from the deleterious effects of glacial mining practices. In 2008, Argentina presented the Ley de Protección de Glaciares (Law of the Glaciers) to its Congress. The law would have afforded a minimum protection to Argentinean glaciers by prohibiting all activity on the glaciers that would damage them. On October 22, 2008, the law passed by a wide majority in Argentina’s Congress with only three votes in opposition. Yet, in a move that surprised many, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner vetoed the law on the grounds that it would have adverse impact on mining industries and impede economic growth. The law was returned to Congress on appeal by proponents but this time the bill did not garner enough support to override the presidential veto.

The veto led to an outcry among proponents who claimed that the President was in the pocket of mining interests, specifically, Canadian mining corporation Barrick Gold which maintains significant investment in the region. These allegations were further stoked when the President was seen meeting with Barrick Gold’s CEO Peter Munk in June of 2010. Over the next year, several different politicians who were unwilling to take the death of the Law of Glaciers as the end of glacial protection, sought to re-introduce similar bills.

These efforts were routinely encountered by fierce opposition from provincial governors and interest groups with financial interests in allowing mining activities to go forward. They argued that if a glacier protection law were passed, Barrick Gold and other miners would not be able to continue with their projects and would be forced to sue the Argentine government for hundreds of millions of dollars in compensation for lost investments. They also contended that banning mining and hydrocarbon drilling in periglacial areas would strip provinces of control over their natural resources in addition to impeding economic activity. Proponents on the other hand, argued that the issue was a human rights one – that mega mining strips citizens of their right to water and healthy environment. Proponents maintained that pollution and climate change have already reduced the amount of healthy water, and that coupled with continued population growth, the country would be facing a water crisis over the course of the century.

As a result of the continued efforts of two politicians in particular, Deputy Miguel Bonasso and Senator Daniel Filmus, in September of 2010, after hours of staunch debate, the Argentine Senate passed a new bill entitled the “Glaciers Act” by a narrow margin. The senate was split almost exactly in half by those senators representing mining provinces who would have profited had the law not passed, and those who considered the environmental impacts to be paramount. This time President Kirchner promised to sign the bill.

The law declares all of Argentina’s glaciers to be “strategic reserves of water” and “public property.” It bans mining and oil extraction in the glaciers’ watersheds, and places strict restrictions on industrial activity in surrounding lands, thereby expanding an earlier definition of what constituted periglacial area. It also established a system to asses the environmental impact of commercial projects and outlined specific penalties for polluters. Part of the bill provided authority to create a National Inventory of Glaciers which will be used to compile information on the glaciers in order to monitor their upkeep and protection.

Proponents celebrated the long awaited bill. Yet, not even one month later, the new law faced another setback. In November of 2010, a federal Judge Miguel Angel Galvez enjoined implementation of the law in the province of San Juan in order to allow a mining community to form an appeal on the basis that the Glaciers Act is unconstitutional. The legal underpinning of the community’s claim stems from ambiguity over who has legislative power over natural resources under Argentina’s constitution. Normally, provinces maintain control over their natural resources but in cases of environmental protection that power is transferred to the national congress. Legal scholars have backed the constitutionality of the Glaciers Act but mining association members have vowed to fight any implementation and contend that provinces have absolute legislative authority over natural resources. The result has been the uneven application of the Glaciers Act.

In recent months there have been urgent calls for the full application of the Glaciers Act. In April, Greenpeace, along with more than 40 citizen’s assemblies, social and environmental organizations and politicians launched a petition on the streets and on their websites calling for “full force of the Law of the Glaciers around the country, urgent implementation of environmental audits and the preparation of interim measures submitted by the company Barrick Gold.” In one week, 75,000 people signed a petition in support of this campaign. Various environmental organizations including Greenpeace, the Environmental and Natural Resources Foundation and Argentine Friends of the Earth are also calling on the government to begin the inventories of glaciers and periglacial areas as soon as possible as no specific timeframe for these measures was set out in the Glaciers Act. Supporters hope that continued pressure will ultimately win out against big business but there is no question that the incomplete application of the Glaciers Act has led environmentalists to question the government’s commitment to the issue.

* Photo source: https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1386i/chile-arg/intro.html