By Rosette Zarzar and Romany Webb

On Friday June 9, Representatives Carlos Curbelo (R-FL) and Marc Veasey (D-TX) proposed a bipartisan bill, aimed at supporting the development of new technologies to address natural gas pipeline leaks. The bill would provide $225 million for research on leak control technologies to, in the words of Rep. Veasey, “chip away at the high costs and current limits of [such] technologies.” While this is a laudable aim, in most cases, new technologies are not required to find and fix pipeline leaks. The vast majority of leaks are known to originate from aging pipelines, made of cast iron or bare steel, and can be easily eliminated by replacing those lines with newer plastic ones.

Approximately 2.6 million miles of pipelines currently crisscross the U.S., moving trillions of cubic feet of gas every year. The pipeline system is generally divided into two key parts:

- the transmission system, which comprises large, high capacity pipelines that move gas from field production and processing areas to large volume customers and local utilities; and

- the distribution system, which comprises smaller pipelines used by utilities to deliver gas to residential, commercial, and industrial customers. Central distribution mains convey gas from the city gate (i.e., the point at which gas is transferred from a transmission pipeline to the utility) to service lines for delivery to customers.

Much of the nation’s pipeline infrastructure is forty to fifty years old. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (“PHMSA”) estimates that over half of all transmission pipelines and a quarter of all distribution pipelines currently in use were installed prior to 1970. Many of these pipelines are made of cast iron, which is prone to graphitization, where the iron degrades and cracks. Cracking may also occur due to corrosion of old bare steel pipelines. This can result in gas leaks which, in addition to wasting a valuable resource, also pose a serious threat to public safety, potentially triggering explosions and/or fires. Moreover, as gas is comprised primarily of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, leaks also accelerate climate change.

Gas leaks, due to pipeline graphitization and corrosion, are a particular problem here in New York City. A 2015 study, in which researchers measured gas leakage along 247 miles of pipeline in Manhattan, found an average of one leak every quarter mile. Another study conducted in Staten Island in 2014 found an average of one leak every mile. In both cases, the authors attributed the high rate of leakage to the fact that New York has one of the oldest underground pipeline networks in the country, with a high proportion of iron and steel pipes.

Concerned about the potential for leaks from aging pipelines, in March 2012, PHMSA issued an advisory bulletin urging operators to accelerate pipe replacement. Operators are, however, often reluctant to invest in replacement programs due to concerns over whether and when they will recover their investment. As the Sabin Center recently noted here, the rates charged by pipeline operators are subject to regulation, to ensure they are just and reasonable. Regulatory authority is shared between:

- the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“FERC”), which sets rates for interstate pipelines (i.e., crossing state boundaries); and

- state utility commissions (e.g., the Public Service Commission (“PSC”) in New York), which set rates for intrastate pipelines (i.e., located entirely within a single state).

Pipeline operators are required to file “rate cases” with their regulator periodically (i.e., usually every few years). Based on the rate case the regulator determines the prices or “rates” an operator needs to recover its legitimate costs. While pipeline replacement costs are recoverable, they are generally not included in prices until the next rate case is filed, with the operator required to carry the cost in the interim.

Recognizing that this may discourage pipe replacement, in April 2015, FERC adopted new rules allowing interstate pipeline operators to recover their replacement costs through a capital tracker. Under the tracker, operators have the option of recovering replacement costs annually, rather than waiting until their next rate case. Similar tracker mechanisms have been adopted, with respect to intrastate pipelines, in 27 states and the District of Columbia.

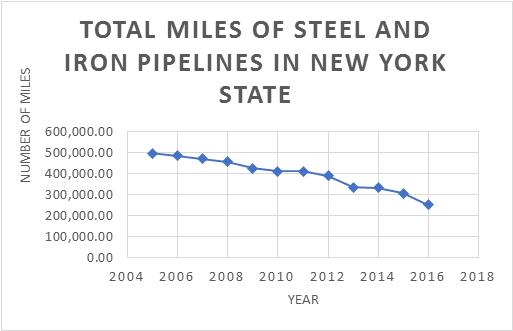

Despite the recent increase in pipe replacement, there remains a long way to go. It is estimated that, in New York City, half of all pipes are still made of iron or steel. At current replacement rates, it will take approximately 30 years to replace those pipelines, meaning that some could remain in service until almost 2050. By that time, corrosion or graphitization could be widespread, leading to even more gas leaks.

With concern growing over the extent of gas leakage, New York PSC Commissioner, Gregg Sayre, recently declared that “accelerating the replacement of leak-prone pipes” is a key “priority” for the PSC. Commissioner Sayre has expressed support for the Governor’s Methane Reduction Plan which, as previously reported, calls for action to reduce pipeline leaks by “remov[ing] barriers to replacement of leak-prone infrastructure.” Arguably the key barrier to replacement is cost. While the cost of replacement varies, it typically averages $1 to $5 million per mile of pipeline, and can reach up to $8 million per mile in urban areas. Con Edison, which operates much of the pipeline system in New York City, recently estimated that it would cost $10 billion to replace all of its leak-prone distribution mains. Replacing service mains would cost even more.

New York’s Methane Reduction Plan calls for the identification of alternative funding models, which do not rely on customers. One option is for the government to step in and fund replacement programs. While that may seem unlikely, it is not outside the realm of possibility. The federal government is already looking at providing $225 million for research into advanced pipeline leak control technologies under the Curbelo / Veasey bill. Just imagine what could be done if a similar amount were devoted to replacing leak-prone pipes.