By Bernard E. Harcourt

The police in New York City,

Chased a boy right through the park.

In a case of mistaken identity,

They put a bullet through his heart.

Heartbreakers, with your forty-four,

I want to tear your world apart!

You heartbreaker, with your forty-four,

I want to tear your world a part!

Oh yeah, oh yeah,

I want to tear that world apart!

Oh yeah, oh yeah,

I want to tear that world apart!

— The Rolling Stones, “Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker),” Goats Head Soup (1973)

New York City. 1973. That was almost fifty years ago. Fifty years!

“I want to tear that world apart.”

The struggle against police killings has been going on for years, for decades. In this country, it goes even further back—to the struggles against police-aided lynchings and the horrors of slave patrols.

And now that we can record the killings and keep track of them—thanks originally to The Guardian and now to The Washington Post—we see with our own eyes that we are making little progress.

Rates of fatal police shootings remain steady and Black Americans continue to be “shot at a disproportionate rate.”

987 civilians have been shot and killed by the police over the past twelve months.

994 in 2015.

961 in 2016.

986 in 2017.

990 in 2018.

999 in 2019.

982 so far this year, 2020.

5,782 people shot and killed by the police since The Washington Post started keeping track in 2015 (as of Nov. 19, 2020).

No, we are not making progress on police violence in this country. To the contrary, if the proliferation of the new thin-blue-line, black-and-white, American flags tells us anything—and the fact that it is now tied to Donald Trump and his 73 million voters—the country is entering an even more dangerous period.

“White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany called attention to the prominence of the flag, tweeting: ‘The Thin Blue Line flag is flying HIGH at President [Trump’s] rally in Wisconsin!’” – Heather Cox Richardson (from Milwaukee Independent)

I’m George Floyd.

I’m George Floyd.

So much blood spilled on the pavement.

I can’t forget the lives they took.

I’m Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Laquan McDonald, Tanisha Anderson…

— Lil B, “I Am George Floyd,” June 6, 2020

* * *

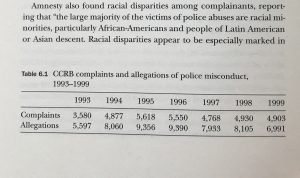

New York City’s police department has always been notorious, but the problems got exponentially worse in the early 1990s during what was called “Giuliani Time” in the city. Rudy Giuliani and his first police commissioner, William Bratton, brought “broken-windows policing” to the city, and, with it, police brutality, surveillance, and inhumanity against the most vulnerable residents of the city—resulting later in the torture and police sexual assault of Abner Louima in 1997, the 41-shots police killing of Amadou Diallo in 1999, and a wave of complaints of police misconduct. Giuliani took office in 1994 and complaints of police misconduct shot up immediately, as evidenced in Table 6.1 below:

Source: Harcourt, Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing (Harvard 2001), page 168.

Kevin Keating, the filmmaker, made a powerful documentary about the times, titled, appropriately, “Giuliani Time.” You might be interested to see how prominently Donald Trump features! And that was decades ago!

Giuliani Time was at the root of much of the policing disorder because broken-windows policing instituted a militarized us-versus-them attitude to policing in NYC. It was conceived as a military assault on criminality, meaning Black criminality. One of the main architects of broken-windows policing, Jack Maple, referred to the strategy as all-out “war.” In his own descriptions of broken-windows policing, Maple referred repeatedly to war strategists from Sun Tzu to Hannibal, Admiral Lord Nelson to Napoleon, and General Patton. The police officers were referred to as “troops in the field.” The police captains were referred to as “skilled, audacious commanders.” And they were each given a field marshal equivalent right out of World War II. As Maple wrote:

Bratton was our George C. Marshall, the man of vision who shook the US armed forces out of their sleep in 1941 and demonstrated an infallible instinct for identifying talent. Chief of Department John Timoney was our Eisenhower, as respected by the soldiers in the field as he was knowledgeable about the intricacies of managing a mammoth fighting organization. Chief of Patrol Louie Anemone was our Patton, a tireless motivator and brilliant field strategist who could move ground forces at warp speed.[1]

This militarized approach to society would eventually morph, after 9/11, into the hyper-militarized police forces that we have become accustomed to today.

* * *

Back in the 1990s, the struggle against policing, and especially broken-windows policing, had abolitionist overtones, but it was not explicitly abolitionist. The language and discourse of abolition had not yet spread from death penalty abolition or prison abolition to the police context.

Nevertheless, a lot of the critiques and proposed alternatives were precisely about moving police functions to other service providers or first responders—so, in effect, replacing policing. So, for instance, in response to broken-windows policing, many argued that even if New Yorkers wanted to reduce forms of “disorder,” they could do so through other means than the police. In other words, there were other social services and first responders who could reduce disorder if that was the goal. That was certainly true in Illusion of Order, as well as in Alex Vitale’s City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics (NYU Press, 2009). As I wrote in Illusion of Order in 2001:

The fact is, even if we want to attack “disorder,” there are many different ways of proceeding. There are numerous alternatives to policies of aggressive misdemeanor stops and frisks and arrests. … Instead of arresting turnstile jumpers, for instance, we can—and New York City has begun to—install turnstiles that cannot be jumped. … Instead of arresting prostitutes, we could investigate the possibility of licensing prostitution. … How can we deal with graffiti? … By an obstinate effort to keep the cars clean. … How can we discourage aggressive panhandling and other forms of street economies? Instead of arrest, perhaps we should explore the possibility of work programs for people living on the street. … There are endless ways of resolving problems of “disorder”—should we want to—short of arrest and incarceration. All we need to do is let our imagination roam within a realistic and practical range.[2]

Today, those responses to policing still seem correct, but too limited. Especially after our conversation at Abolition Democracy 3/13, it is clear that we can analyze the solutions to police violence through the lens of redistributing the functions of the police. But to be honest, that approach feels too functionalist, too limited, and not sufficiently ambitious given the scope of the problem and given that we have, to date, made no real progress in addressing police violence. It does not pay sufficient attention to the deeper political-economic forces that pervade policing in the United States today. It feels too much like finding a quick policy fix for a problem that goes deeper and that is likely to replicate itself if it is not addressed at a more fundamental level.

In this sense, American society needs to be transformed more ambitiously in order to root out the conditions that give rise to policing and its violence. Violence interrupters, as I will show, may be a pragmatic solution to the remainder that is always present when we talk about “defunding” the police. But we need to be far more ambitious in our efforts to create a just society.

That is the ambition, and the lesson, of the 3/13 seminar on #AbolishThePolice and, more broadly, the seminar series so far on Abolition Democracy.

Piecemeal policy reforms will not succeed in substantially transforming society so long as we do not instantiate the broader ambition of abolition democracy: not just abolition of unjust institutions, but the reimagination and construction of new just institutions and the enactment of a new political, social, and economic reality. This was, in part, the lesson of Abolition Democracy 2/13.

The Framing of 3/13

We had emerged from the last seminar, Abolition Democracy 2/13, with a far better grasp of the full ambition of abolition democracy – the ambition to, not just abolish our punitive society and the institutions of racial injustice, but more positively to envision and put in place the framework and institutions to create a just society, and as part of that a new political economy. We spoke of the need for new practices of education and justice-in-education. We spoke of the need to transform economic relations—one of the most central forces in Du Bois’s and Angela Davis’s work. We spoke of abolishing the practices and institutions tied to the repression of Reconstruction and to the reign of terror that followed the Civil War, especially in the South.

It is within that framework that we approached the police in 3/13: one of the central institutions in the arsenal of repression and racial injustice. Policing and criminal law enforcement were, and are today, the lynchpin in the new mechanisms, post-slavery, to recreate a racial hierarchy in this country. The police, with its long legacy going back to the function of maintaining slavery and the social ordering of the antebellum period; with its history of facilitating and collaborating with decades of terror, with the Klan, with the lynchings; with its practices in the 20th century of racial profiling, broken-windows policing, hyper-militarized policing, and now that we are able to see it—now that we are able to record it—with the atrocity of constant, repeated, unending police killings of young Black men and women. The police, with all this history, has become a central mechanism to maintain our caste society.

You will recall from last session, W.E.B. Du Bois detailing the reign of terror after the Civil War. How the South looked backwards to reenact the conditions of slavery. How it relied on the Black Codes and the Klan and armed militia. How it sought to establish, in the words of Carl Schutz, “a new form of servitude.”[3] The period after the war was truly a reign of terror.[4] As Du Bois wrote, “war may go on more secretly, more spasmodically, and yet as truly as before the peace.”[5]

Police violence today is the legacy of that reign of terror. Its continues today and the continuities are so brilliantly captured by the artist Dread Scott, in this artistic rendition of the earlier famous flag that flew from the offices of the NAACP in NYC—that flag bearing the words “A man was lynched yesterday” that was flown from the national headquarters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) between 1920 and 1938 to mark lynchings of black people in the United States. Dread Scott was inspired to created this artwork after the 2015 shooting and killing of Walter Scott, an unarmed Black man, stopped for a traffic violation, shot dead while he was running from a police officer in South Carolina.

996 people have been shot and killed by police in the past year. Breonna Taylor. George Floyd, and just in October. Jonathan Price. Fred Williams III. Marcellis Stinnette. Mark Bender. Walter Wallace Jr. just a few weeks ago in Philadelphia.

And before that, so many other young Black men and women. Such as Matthew Felix, a 19-year-old young man, who was shot multiple times and killed in front of his home in Queens in February 2020. Matthew Felix was unarmed, posed no threat, and the officers who shot and killed him in Queens were plain clothed Nassau County police who were outside of their jurisdiction when they took his life.

The history is damning. Not just in the origin stories of policing, which in important respects trace to slave patrols in this country, but in the history of police violence, a form of terror that is being felt today across America today.

Reallocating the Police Functions

A first step to address the problems of policing would be to reallocate the functions of policing. Many progressives and abolitionists agree that a lot of what the police do could be done better by other social services—mental health, housing, sanitation, drug rehabilitation, etc.

The one point where there is critical disagreement is whether there remains, at the end of the day, a proper function for the police. That remainder is conventionally expressed as “maintaining order,” “preventing crime,” or “stopping violence.” The core function of the police that progressives are prepared to recognize is “public safety.” As Tracey Meares and Tom Tyler write in The Atlantic, their “hope is that policing becomes one component of public safety and vitality.” The one core function that often remains is dealing with violence in society.

But rather than use the police for that remaining function, a just society would turn instead to a model of community-based violence interrupters. This is an approach that has been developed in cities around the country and that aims always to deescalate violence and confrontation.

As we have repeatedly seen over the last months, armed police officers tend to escalate violence. A big part of the problem is the warrior mentality that has evolved within the blue ranks—what Seth Stoughton refers to as the “warrior mindset,” what Radley Balko calls the “warrior cops,” what Vitale refers to as “soldiers at war,” or what I have written about under the rubric of the “counterinsurgency warfare paradigm” of policing. As a result of decades of conflict, the police today tend to adopt an “us and them” attitude that more often than not escalates, rather than deescalates violence and conflict.

The violence interrupter model, by contrast, is dedicated to one goal: to find ways to deescalate and avoid violence. The model of violence interrupters is a well-developed approach, originally conceived on the basis of a public health paradigm by an epidemiologist, Gary Slutkin, and first applied in projects in Chicago including Ceasefire and Cure Violence. Treating violence as contagious, the approach seeks to interrupt the cycle of violence by changing norms and expectations, finding alternative behavioral pathways, and addressing family and health needs.

Violence interrupters are trained to assess situations from the perspective of the needs of the individual and to deploy a wide range of tools to defuse conflict; they also locate their interruptions within the broader context of community mobilization, public education campaigns, and the provision of services such as GED programs, anger-management counseling, and drug or alcohol treatment. Violence interrupters are often recruited from within the community and have life experiences that give them a level of credibility in the situations in which they intervene.

Many of the existing projects have met with success. According to statistics collected by Cure Violence Global, some of these programs have been effective in the South Bronx and Brooklyn, in Chicago , and elsewhere. To be sure, some of the projects have encountered difficulties. Conflict can flare up after violence interrupters leave. Some of the mediated agreements are not always followed through on. But all approaches will encounter difficulties. The question is which ones minimize, rather than aggravate the situations of conflict.

The point here is not to promote any one particular violence interrupter program or provider, but instead to highlight a far more promising path to deal with the single remaining function of the police. The violence interruption model is far better than most police interventions because it has one ambition, and the right one: to defuse conflict, to deescalate situations of violence. That is what we need to be doing to make society safer and more just.

Transforming the culture of an institution like policing is not promising. Instead of armed cops with a warrior mindset coming into violent, combustible settings, we need to have people who are dedicated to one goal: interrupting violence and de-escalating conflict.

That would have saved Eric Garner. It would have saved George Floyd and prevented the killing of Breonna Taylor. It would have avoided the tragic shooting of Jacob Blake. It would also eliminate the “us and them” mentality that has turned so many neighborhoods, especially Black and Latinx neighborhoods, into war zones.

We should not avoid the most critical question in the new national debate on policing. We should not sweep it under the rug with the convenient term “defund.” Instead we need to face the question head on. And when we do, it will become clear to many that the core remaining function of the police would be better carried out through a violence and conflict interrupter model.

A More Ambitious Abolitionist Vision

But this response, although correct, seems too limited now. It does not take account of the deeper structural forces that lead to police violence.

What Abolition Democracy teaches us is that we need to reach further, to go deeper, in order to imagine a different society entirely. Not just to redistribute functions, but to reimagine society. Not just to abolish those institutions, but to dismantle the very society that makes those institutions possible. “Not so much the abolition of prisons,” as Moten and Harney write, “but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.” (42)

For many, abolition is something we have grown into. Whether it is in the context of the death penalty or of prisons, or of policing, many of us were not born abolitionists, but got there through circuitous paths. As Derecka Purnell writes in her Atlantic essay, “’Police abolition’ initially repulsed me. The idea seemed white and utopic. I’d seen too much sexual violence and buried too many friends to consider getting rid of police in St. Louis, let alone the nation.”

But like Derecka Purnell, many have now given up on reform and now embrace abolition.

The paths there are very different.

For some, it was through the civil rights movement and “Know Your Rights” initiatives. Amna Akbar spoke poignantly about her own journey to abolition from her earlier work as a lawyer apprising Black, brown, immigrant and Muslim communities of their rights in their constant confrontations with the police.

For others, it was through critiques of broken-windows policing. Alex Vitale spoke powerfully of his abolitionist journey advocating for the homeless 30 years ago and being confronted by the criminalization of poverty and the assault of misdemeanor arrests under the broken-windows theory. Josmar Trujillo as well began fighting against broken windows policing decades ago—actually that is how we first met, probably two decades ago.

For others, like Samantha Felix and Ghislaine Pagès, it is the constant terrifying drumbeat of police killings of young Black women and men. “How much time do you want for your progress?” Ghislaine Pagès asks with James Baldwin.

For many, it is the futility of reforms.

Abolition comes with many origins stories.

And now, more than ever, it is the path to explore, to critically examine, and to forge. If we don’t, I fear, we will simply replicate the problems of the past. Retaining police officers in the schools, but simply switching the funding line from the NYPD to the Department of Education will not really address the problems, but allow them to reproduce.

The place to begin, I firmly believe, is to listen to the conversation between Amna Akbar, Samantha Felix, Ghislaine Pagès, Derecka Purnell, Josmar Trujillo, and Alex Vitale at the seminar Abolition Democracy 3/13.

“A mandate within abolitionist work is for building connections to each other and collective resilience—to be led by the collective rather than the individual, to think collaboratively and horizontally. These demands should push all of us to rethink what we do and how we do it.”

—Amna Akbar, “An Abolitionist Horizon for Police (Reform)”

Notes

[1] Jack Maple and Chris Mitchell, The Crime Fighter: Putting the Bad Guys Out of Business (New York: Doubleday, 1999), 31.

[2] Harcourt, Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing, 221-224.

[3] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 136.

[4] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 671.

[5] Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 670.